by Scott Essman

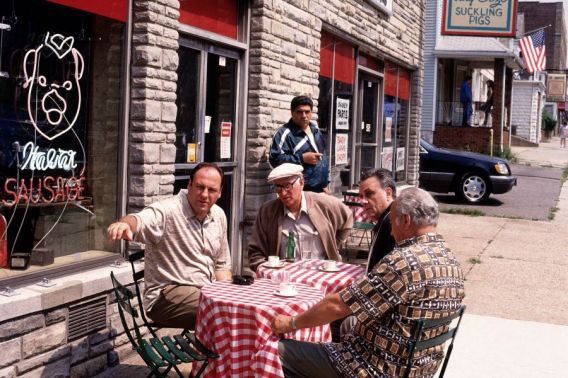

In the spring of 1999, after just 13 episodes, the HBO series The Sopranos had created as much buzz as any TV program in recent memory. The brainchild of executive producer David Chase, The Sopranos is now into its second season. It features a dynamic cast with production values that are polished but never obtrusive. Already, the show has returned to the forefront of both public and critical attention, garnering Golden Globe awards for best dramatic television program, for its two leads-James Gandolfini and Edie Falco-and for supporting actress Nancy Marchand. What’s more, editor William Stich, ACE has received an Eddie nomination for his work on last season’s finale.

The Sopranos is a prime example of the popularity that television programs can achieve without the support of the major networks. After Chase developed the basic idea for the show, none of the big four networks were interested. This blessing-in-disguise eventually lead Chase to HBO, where the show is appropriately free from the effects of censorship. Hence, The Sopranos offers viewers an unbridled look into the world of a Mafia boss (Gandolfini) and the two “families” with whom he struggles-in his domestic life and his business life. The intimacy with which the show’s characters are presented, combined with the energy of its plotlines, makes for powerful and compelling entertainment.

In this interview, conducted in early January, the current season’s three picture editors – Conrad Gonzalez, Stich, and Sidney Wolinsky – offer their thoughts on all things Soprano. The three exuded confidence and pleasure as they spoke about the elements that comprise The Sopranos.

How exciting is it to work on a show that has so quickly achieved this much popularity?

Conrad Gonzalez: Part of you is excited about it, and another part of you is almost wondering if it’s really happening. In all my years in the business, I haven’t ever been attached to a hit of this magnitude. It’s thrilling to see it happen for David Chase because he’s one of the few filmmakers I’ve worked with who’s had such a singular vision.

“I don’t feel, as an editor, that David would ever turn to me and say, ‘Stop being creative. This is the way I’m going to do it. It’s my show.'” – William Stich

In what ways would you say that is true?

CG: David is very particular and just knows what he wants. It’s not that he doesn’t experiment or try things during the cuts, but he has a certain sensibility and a strong vision of how he sees the show. He truly uses the post-production process as a final rewrite, unlike many TV shows where they’re more attached to their words and scenes and moments. The Sopranos takes on a new life in post because David will get in there and really cut an episode.

Why would this show, which shoots in New York and New Jersey, have its post-production occur in Los Angeles?

CG: The decision was made because David comes back to his home in Los Angeles to work with us directly after principal photography is completed on the season’s episodes. During production, we send tapes back and forth, get notes from David, and send cuts to him back east.

How is that system organized?

CG: We try to deliver a really terrific first cut, a foundation to start from. While he’s on location, David views the shows by himself, his assistant takes down notes, and they get faxed to us. We execute the notes and Fed-Ex the cuts back to him. What we lose is the one-to-one interaction with him in the cutting room, but David’s notes are so direct and specific, it all works out.

How do you feel about the secrecy in which the show is shrouded?

William Stich: It’s very important for the series because it has this enormous artistic aspect. The whole process is very secretive. David wants to keep it that way so that when an episode airs, the audience doesn’t know what they’re going to get and it’s more fun. Part of the show’s premise is to keep everything a secret.

When is it determined who is going to cut various episodes amongst you?

Sidney Wolinsky: It is simply a rotation: each of us cuts every third show. The only decision is the order in which each person starts. There are thirteen episodes, and I cut the first one, so I cut five in total, and Bill and Conrad cut four each.

Could this show be produced at the same quality level if it were a full season’s worth of episodes?

CG: I think a lot of care is taken with the scripts,so I’m not sure that that many scripts of that quality could be generated in the same amount of time.

What is the shooting schedule for each episode?

SW: They shoot an episode in eight or nine days, depending on the complexity of the show.

CG: Normally the intention is to shoot an entire edpisode and then move on, but because there are so many company moves in every show they don’t always achieve it. They lose a lot of time and sometimes work ungodly hours to get the show done. As the season progresses, we inevitably see some additional shooting either because things were missed in the original shoot or, less frequently, for story reasons.

With three of you editing and at least five directors working on various episodes, is it difficult to edit The Sopranos in a consistent manner?

WS: It’ s basically the David Chase show, and you get a feeling for his pacing through the scripts. You’re not dealing with three or four producers, you’re dealing with David Chase, and he lets you know where he’s trying to go with in the direction of a scene. It’s not like we’re just randomly doing something and then making changes for one producer who has an idea how a scene is supposed to be, then going in and trying to restructure it again for another producer who has a different idea. We’re dealing with one vision, which is David Chase’s.

Doesn’t that limit your ability to bring creative ideas to the show?

WS: I don’t think that David ever squelches anything that we want to do creatively, but there is a direction that he has in all of the shows. It’s a major plus that we’re dealing with his vision. I may go off in a direction and he has never said, ‘I hate that.’ He’ll let you try something, and then he’ll rein you back in if you’re going the wrong way. I don’t feel, as an editor, that David would ever turn to me and say, ‘Stop being creative. This is the way I’m going to do it. It’s my show’ He always has said that this process is very collaborative, but it’s nice to have a vision that you can follow; as a film editor, that’s great.

CG: The nature of what we do is help other people realize their vision, and it’s easier to do that if the person you’re working with knows what they want. The more the person knows what they’re after, the easier it is to help them get to that place.

SW: The more input I can get from the people I’m working with, the better I can function to help them get what they want.

“Our job is to figure out how to tell the story in the scenes. We don’t omit lines; we put everything in script order.” – Sidney Wolinsky

With regards to your involvement as a team, how does The Sopranos maintain such a consistent tone from show to show?

CG: One of the things that’s valuable to us, in terms of how David sees each scene, is that we have tone meetings before each production. It’s usually attended by David, the director of that show’s episode, the writer of that show, a few key production people, and the editor. They conference us on the telephone while they meet in New York, and we go through the script, beat by beat, scene by scene. Thus, David makes the dramatic intent of the scene perfectly clear to the director. Then, we take that knowledge from the tone meeting and we’re able to facilitate that into our first cuts-our thoughts have already been impregnated with the specific intentions for the script. That’s very valuable in the sense that we’re not really interpreting in regards to the editor’s cut. On the other hand, David respects our craftsmanship and gives us a lot of free reign in terms of how we cut the shows. Then he just gets very specific about the pace, and works the script in the final cut.

What is the outcome of the tone meetings from the editors’ point of view?

SW: We have the opportunity to ask questions if we don’t understand something in the script, and the production people will have an opportunity to get things clarified. Everyone starts the show on the same page, no pun intended.

Once a show has been shot, how long do you get to create your editor’s cut before the director’s involvement?

SW: We have five days after we get our last dailies to present an editor’s cut to the director of that episode. Typically, we send the editor’s cut to the director, or sit down with the director and look at the editor’s cut, depending on where the director is. And then the director contractually has four days for his cut. That’s the DGA stipulation on a one-hour show. Then the episode goes to David, and he has as long as he wants until the airdate.

Can you describe your interaction with the director during the four days he has for his cut?

SW: If the director is in Los Angeles, he will come to the cutting room, and either run the show and give us notes, or run the show and sit with us while we execute the notes. If he’s in New York, we go through the same procedure with him as we go through with David, which is, we send him a cut, and he will give you notes over the phone. Sometimes you’ll spend a number of hours on the phone while he runs the show and gives you notes. Then you will execute his notes, send him the cut, get more notes, and finalize his cut. Once it’s locked, it is sent to David.

Due to David’s involvement in the show, does the director have a reduced input in the way that an episode is edited?

CG: If directors in series TV are successful, they have a whole season of commitments to do various shows, so they usually have to move on to prep their next show. On The Sopranos, two of our directors do outside work, and our one staff director, Alan Coulter, is very meticulous and very involved in his director’s cuts. He has a clear vision of how he shoots it and how each scene is worked out thematically. He likes to get on the phone and go over the show for two hours while he’s running his cassette with you at your Avid. But again, in series TV, it’s an executive producer’s medium, not the director’s, as in feature films.

Is each of you often cutting more than one episode at a time as the shooting company completes their work on your different episodes?

WS: Yes, but that’s the basic nature of series television. I’ve never worked on a series television show where it’s, ‘Oh, boy! I’m done with my show. Now I can go start cutting on my new one.’ And it makes it difficult to jump back and forth between your episodes. Our producer (and one of the episodes’ directors) Martin Bruestle is very good about adjusting the schedule, so that, if we are in an editor’s cut on an episode, and get notes from David on another episode, we can address those notes and then go back to the show that’s in its editor’s cut without losing the time we need to complete it. Then David has a chance to look at that show and then we can try to get our first cut together.

CG: Also, we have terrific assistants (April Lawrence, Gerald Valdez, and Lynne Whitlock), who are highly organized and make that all easy for us. The shows are all on line and we have enough memory in our drives to carry all of our shows with us simultaneously.

In what format is the show produced and edited?

SW: It is shot in 35mm, shipped here for processing at CFI and telecined onto Digital Betacam at Riot. Then we receive 3/4-inch video dailies that we digitize into the Avid. For air, we do an on-line – associate producer Gregg Glickman supervises all of the final finishing, and Martin Bruestle supervises the sound dub and music.

How are a majority of the songs and music chosen for the show?

WS: Sometimes the scripts specifically say, ‘For this scene, so-and-so is playing in the background.’ Martin and David work very closely on the music for The Sopranos. Martin is constantly working to find new and different music for the show. David may say, ‘Hey, Martin, let’s see if we can get this song for here,’ so Martin is constantly on the move, trying to figure things out.

“The nature of what we do is help other people realize their vision, and it’s easier to do that if the person you’re working with knows what they want.” – Conrad Gonzalez

For this year’s first episode, the choice of FrankSinatra’s ‘It Was a Very Good Year’ in the opening montage helped set the tone for this entire season.

SW: That was chosen at the script stage. They played the song back on the set to kind of get the pace of it, but it wasn’t really shot to the song.

To what degree do you all follow the scripts?

WS: In a first cut, the way I was trained, you follow the script. Every director or executive producer that I’ve ever worked for wants to see first what’s written on the paper. Then they’ll move scenes around and change things, but the script is what they bought. If you run into a problem, and you can’t make a transition, or you feel that something should go in an area, you can talk to them and do it. But on this show, you put your cut together per the written page.

SW: Our job is to figure out how to tell the story in the scenes. We don’t omit lines; we put everything in script order. Sometimes you get a phone call saying, ‘I shot something a certain way. Try it this specific way.’ But that is the exception rather than the rule.

CG: It’s part of the job as an editor to interpret the footage, unless you’re given specific notes on how to put it together. But I find that it’s always more comfortable for me to figure out how the pieces of the puzzle go together. Editing is a very instinctual job where a lot of what you do comes from your gut. Ultimately what I try to put in my first cut is what works for me. Unless you worked with a director that had a very clear vision, and he could just spell it out for you, I think that’s really what the editor’s job is. I think all three of us take pride in the choices we make in our first cuts. And, on this show, much of a good first cut’s internal editing will survive the final cut.

Could The Sopranos work as effectively on one of the big three networks?

WS: You wouldn’t have the nudity, the profanity, and the violence in it, but I think the show would still have the conflicts, which, to me, is why most people enjoy the show: the drama between Tony and his mother, his children and his wife. Even though the profanity couldn’t be used, those inherent relationships would still work. And I think that on the other side of the family that he deals with, being the Mafia side, those conflicts would still work, too. Because it’s on HBO, we now have a great deal of freedom, but I think the scripts are structured well enough that they could still survive and it would be a popular show on a network.

SW: It’s one of those hypothetical questions, but I think everything would be so different if this were a network show, that it would just be an alternate universe. From the very ground up, it would be different-having nothing to do with us. Would the casting be the same? Would the same scriptwriters be hired, apart from David? Would the schedule be the same? There’d be a demand for more-they’d have to be doing 20 to 25 shows.

CG: I think the show would probably be neutered, and the conflicts wouldn’t be allowed to be as extreme; they might try to make, for example, Tony Soprano’s mother, Livia, more likable. We wouldn’t be allowed to go to the extremes that we go to. They’d try to reach more of a cross-section audience. We couldn’t go over the edge, press the envelope. I don’t know that it would as successful-the tone of the show would surely be altered.

Is it an extra plus to have a leading man like James Gandolfini around whom you can build your scenes?

CG: Oh yes. I coined the phrase ‘Gandolfini, the man with a thousand expressions.’ Sometimes he says more with silent reactions than he does with the written word, and he goes to places inside of himself and pulls these looks up. It’s rare that an actor has that ability to go to so many different places.

WS: He’s always working and gives you a performance that is sometimes unbelievable, unusual and new. It’s a pleasure, but I think that goes for all the cast. I can’t think of times where I get bad performances.

Do you think the manner in which you create the individual episodes of this show approximates the way in which you work on a feature film?

WS: It depends on the director. Some are very expeditious with their film because they have their vision of how they want the scene to go together. With other directors, you’ll get a lot of footage, and it’s not because they don’t have a vision; it’s just what they do — they just shoot a lot of film. On this show, we generally average an hour, sometimes up to an hour and a half of dailies, which is not above the norm.

“I find that it’s always more comfortable for me to figure out how the pieces of the puzzle go together. Editing is a very instinctual job where a lot of what you do comes from your gut.” – Conrad Gonzalez

CG: My answer would be yes. As I mentioned earlier the show started production in early July but our first airdate wasn’t until mid-January. Because of this we have the rare opportunity to take our time in post, which is contrary to most television series’ post schedules. David is afforded the time to work with us to make the best shows possible. A typical Sopranos episode might go through a dozen or more major recuts. In this respect, we have the luxury to shape our shows much like you would on a feature.

What will the remainder of your schedules consist of now that the second season has wrapped?

SW: They will finish shooting in a few days. Then, David will be back here, and we’ll start to lock all the shows.Within about a month, by the end of February, I think we’ll be all finished.

William, what was your reaction to being nominated for an ACE Eddie Award for your work on the show?

WS: It’s a terrific honor, and David is a very exciting person to work with. He’s a wonderful filmmaker– he cares about the product that he’s working on. It’s a thrill to work with him and I’m enormously proud and happy for myself, especially since it happened on The Sopranos — I know that a lot of what went on in the cutting room came from David. I feel very fortunate because this show is a lot of work, but it’s fun, too. And it’s nice, getting paid to work on something that’s fun.