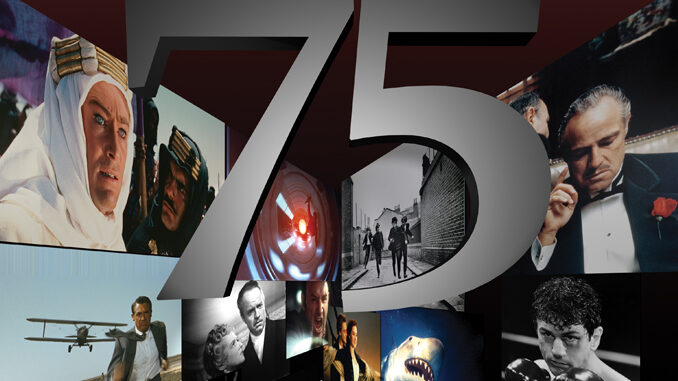

Since CineMontage is celebrating the history of the Motion Picture Editors Guild and its members all throughout 2012, in this issue — which coincides with the 75th birthday of the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors (May 20) — we decided to honor the art of post- production. And what better way than with a “best of ” list?

In our JAN-FEB 12 issue, we asked Guild members to vote on what they consider to be the Best Edited Films of all time. Any feature-length film from any country in the world was eligible. And by “Best Edited,” we explained, we didn’t just mean picture; sound, music and mixing were to be considered as well. Members could submit up to 10 film titles, numbered in order of preference. From those votes, we compiled the resulting list, weighting the films accordingly, and arrived at the 75 you will find in the following pages.

While the final tally definitely reflects a keen post-production perspective, it also doesn’t seem to be all that different than what an electorate of film critics or die-hard movie buffs might choose if presented with the same challenge. In other words, the list does not read like an insider’s compilation of esoteric motion pictures that were created — or even salvaged — in the cutting room or on the mixing stage.

Editing may be called the “invisible art,” but great post work remains recognizable to many — even if it doesn’t overtly call attention to itself. Indeed, our 10 top-ranked films were all Academy Award winners, nine of them scoring multiple Oscars. The five highest-rated titles on

the list (which also receive critical appreciations from CineMontage’s contributing film scholars) have 11 Oscars among them, and an additional 33 nominations.

We’ll have several more statistics on the results later in this issue, but for now, take a look at what the membership of the Editors Guild, on the 75th anniversary of its founding, chose as the 75 Best Edited Films of all time…

– The Editor

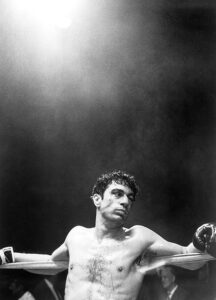

1. Raging Bull (1980)

Directed by: Martin Scorsese

Picture Editing: Thelma Schoonmaker

Supervising Sound Effects Editor: Frank Warner

Re-Recording Mixers: David J. Kimball, Donald O. Mitchell, Bill Nicholson Music Editor: Jim Henrikson

It is easy to forget that there is rarely such a thing as an instant classic. Take the case of Raging Bull. While Martin Scorsese’s seventh feature film was widely acclaimed when it was released in November 1980, some of the director’s greatest admirers (such as critics Pauline Kael and Dave Kehr) did not embrace it unreservedly. Even so, the film was nominated for eight Academy Awards that year, with Robert De Niro winning Best Actor and Thelma Schoonmaker, A.C.E., winning Best Editing.

In hindsight, it makes sense that the Academy, in honoring De Niro and Schoonmaker, would seize on two of the most obvious achievements of the film: its bravura acting and its incandescent editing. In fact, the two are deeply connected. It would be impossible to fully appreciate the size and scale of De Niro’s performance as troubled boxer Jake LaMotta (“The Bronx Bull”) were it not for the film’s brilliant jumps in time. It is through the film’s editing, the way Schoonmaker cuts between time periods with such ease and grace, that we see LaMotta devolve. The first time cut in the film is its most devastating: Schoonmaker takes us from a close-up of La Motta in 1964, paunchy and balding as he prepares for his one-man show, to a close-up of him in 1941, lithe and indestructible-looking in a match with Jimmy Reeves in Cleveland.

The great writer A.J. Liebling, who wrote so eloquently about boxing in The New Yorker magazine, once observed, “Watching a fight on television has always seemed to me a poor substitute for being there.” While Liebling died almost two decades before the film came out, I think he may have felt differently about Raging Bull. Scorsese does not merely re-create the sensation of “being there” in the sense of observing the fights from afar. Rather, as Vincent LoBrutto noted in his definitive book on the director (2007’s Martin Scorsese: A Biography), “The fight scenes in Raging Bull stay inside the ring because the point of view of the images and sound are emanating from inside Jake’s head.”

Instead of a total view of the action, then, we get impressionistic bits and pieces: the punches thrown, the bodies bouncing against the ropes like rubber bands, the card reading “Round 8” that Moments later, when seems to float along the screen, the microphone descending from mid-air and, of course, the flashing bulbs of the cameras. These elements are singled out in close-ups and insert shots, cut together by Schoonmaker with such rapidity that their cumulative effect is disorienting.

As Kael wrote in her review, “We’re meant to see the fists coming as they see them, and feel the blows as they do; the action is speeded up and slowed down to give us these sensations, and the sound of the punches is amplified, while other noises are blotted out.” As a contrast, consider the brief shots shown of the televised broadcast of a match between LaMotta and Sugar Ray Robinson, which LaMotta’s brother, Joey (Joe Pesci), watches on a tiny set; the grainy images give only the scantest impression of the fight — we have been spoiled by the dynamism of the approach taken by Scorsese and Schoonmaker. It is little wonder Liebling felt the way he did.

On the audio side, the film is celebrated for its use of themes by opera composer Pietro Mascagni, which music editor Jim Henriksen folds in sometimes at the least-expected moments. Kael was right to focus on the sounds heard in the ring, too. In fight after fight, we become accustomed to the oomph of the boxing gloves and the tinny ding of the bell, a tribute to the marvelous work of, among others, sound effects supervising editor Frank Warner, sound effects editors William J. Wylie, Chester Slomka and Gary S. Gerlich, and re-recording mixers David J. Kimball, Bill Nicholson and Donald O. Mitchell.

Even in the film’s domestic scenes, the story is often seen from LaMotta’s perspective.

Think of the first few times he gets a glimpse of Vickie (Cathy Moriarity), a “neighborhood girl” who eventually becomes his second wife and the mother of his children. When he first takes notice of her, they are on the opposite ends of a swimming pool swarming with people.

Schoonmaker artfully cuts between shots of LaMotta straining to see her and shots of Vickie masked by the mass of people criss-crossing in front of her. Moments later, when he sits down with Joey and asks him about her, Schoonmaker intercuts their conversation with shots of Vickie beside the pool; the intercutting stresses the gap that exists between them. As he later tells her, “You’re so far away. It’s like you’re on the other side of the room.”

One of the great images in the movie comes when LaMotta takes Vickie out for a round of miniature golf: Stooping in front of a little steeple as she searches for the ball, Vickie turns to him (standing right behind her) and looks to the camera, which is pushing in on her slightly. The shot is as striking as the introduction of Grace Kelly in Rear Window, and yet Schoonmaker holds it only long enough for us to appreciate the smooth camera movement. The cutting has an unusually quick, delicate quality, which contrasts with the many brutal encounters the two will have after they marry.

And yet, the fights in the film are no less beautifully captured. LoBrutto rightly observed that, in life, LaMotta “was not a stylist or a dancing master like his chief rival, Sugar Ray Robinson, but a man who fought like an animal,” and yet all but the bloodiest fights in Raging Bull have a strange elegance to them. This is attributable in large part to the handiwork of Schoonmaker and her post-production colleagues. It is thanks to them that we can see the profound resemblance between editing and boxing. The rhythm of shots and reverse shots is so much like the exchange of punches and counterpunches. The difference between a cut and an uppercut seems, in the end, very slight.

– Peter Tonguette

2. Citizen Kane (1941)

Directed by: Orson Welles

Picture Editing: Robert Wise

Sound Supervisor: John Aalberg (uncredited) Recordists: Bailey Fesler, James G. Stewart Music Editor: Ralph Bekher (uncredited)

Citizen Kane’s stature in American and world cinema is unquestioned. That its central figure bears some resemblance to newspaper publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst ensured the movie’s notoriety upon release — as well as Hearst’s enmity. But that has little to do with its achievement as a film.

Through its main character, Citizen Kane traces 50 years of American social history. The story of a businessman who shapes the growth of American print media, it provides us with a perspective on a nation transforming into an industrial economy and positioning itself for global dominance. To achieve this perspective on business and power won at the expense of personal love and family, director and star Orson Welles collaborated with Herman J. Mankiewicz on its Oscar-winning original screenplay to develop a “cubist” narrative structure with the character creating the story.

In their script, six different personal perspectives on the character of Charles Foster Kane — overlapping in the story’s chronology — are joined together to portray the man and his times. The influence of Kane’s modern novelistic story structure did not become fully apparent until Akira Kurosawa’s films, Rashômon (1950) and Ikiru (1952), and the rise of the personal film with the French New Wave.

Among the nine Oscar nominations that Citizen Kane received, three were for categories in which the film broke new cinematic ground: Gregg Toland’s black- and-white cinematography, Robert Wise’s editing and the sound recording of RKO’s Sound department under the (uncredited) supervision of John Aalberg.

The film’s consistent attention to the sound ambience of its locations is unlike anything heard in movies up to that time. Working with recordists Bailey Fesler and James G. Stewart, Welles experimented with ideas he developed producing the Mercury Theatre on the Air dramas for CBS Radio. Early in the film, the palpable hollowness of a newsreel projection room focuses our attention on the newsmen’s conversation that establishes the movie’s story. Shortly after, at a night club, the resonant voice of the reporter standing in a phone booth contrasts sharply with the waiter’s muted tones outside the booth.

The sound builds a thematic resonance, as well. Sharp footsteps heard early in the vast space of the Thatcher Foundation, established by Kane’s despised guardian, are matched much later by the reporter’s footsteps walking among Kane’s possessions in his palatial mansion, Xanadu.

Subtle yet surprising sound montage effects are built throughout the film. After Kane’s political rival exposes his “love nest” to Kane’s wife, the enraged publisher shouts down the stairs after him. As the machine politician closes the street door to join Kane’s wife outside, Kane’s words meld smoothly into the car horns of the street ambience.

The music editing of the uncredited Ralph Bekher also enhances the sound montage. After her suicide attempt, Kane’s mistress and now second wife lies in bed talking to him as he sits with her. Under her words, almost imperceptibly, weave the themes of the opera that Kane forced her to perform in theaters all over the country to prove her talent as a singer.

Unhappy with his original picture editor, Welles asked the studio for another and was assigned future director Wise. At 26, less than a year older than Welles, he had started at RKO as an assistant sound editor in 1934 and worked his way up to editor on major studio projects.

Much of Kane’s dramatic power stems from the uncut, long-take scenes shot in a revolutionary deep-focus style. In gratitude to cameraman Toland, Welles insisted that the directing and cinematography credits be placed on the same card. But Wise contributed expert facility with a broad range of editing styles that effectively framed those scenes.

While the movie’s meticulous matte dissolve effects — like the opening approach to Xanadu — were planned prior to production, Wise applied a keen sense of rhythm to the sequences that telescoped the years into entertaining minutes. In the most renowned of these sequences, he inserted whip-pans into the depiction of 15 years of breakfasts shared by Kane and his first wife — from honeymoon to cold silence — that also serves as a history of early 20th-century fashions and home décor.

“The concept was there,” says Wise of the scene in a 2001 interview with Jeffrey M. Anderson on the Combustible Cinema website. “But the feeling of it, the pacing of it, the rhythm of it was done in the editing.”

Equally adept is the montage leading from Kane’s first meeting with his second wife through his campaign for governor to the huge rally from which he leaves with the first Mrs. Kane in a taxi to go to his “love nest.” Another piece of telescoping is accomplished in a split second: Young Charles gets a sled as a present from his guardian and scowls, “Merry Christmas!” and a simple cut takes us to the guardian ten years older turning to the camera in exasperation with the words “…and a happy new year!”

Wise is also responsible for the “News on the March” newsreel of Kane’s life, a spot- on parody of the March of Time newsreels. He dragged its fictional footage over the floor and rubbed it in cheesecloth filled with sand to match the scratchy texture of stock footage going back 40 years.

In the 2001 interview, Wise is asked about the often cited “flub…that no character actually hears Kane say his famous last word, ‘Rosebud.’” Even though Kane’s butler Raymond tells the reporter near the movie’s end that he heard Kane say “Rosebud” and drop the snow globe, there is no trace or shadow of his presence in the opening death scene. Also, the dialogue and the tones of the voices suggest that the newsman thinks Raymond may have said it just to get the $1,000 reward for solving the word’s mystery.

The succession of shots in the scene are: A close shot of the snow globe in Kane’s hand, Kane’s lips saying “Rosebud,” the hand letting the globe fall, the globe breaking, a distorted shot of the nurse opening the door, a slightly longer shot showing the distortion in the broken glass shard as she walks out of the shot to the bed, the nurse crossing Kane’s arms and pulling the blanket over his head. It is not clear that the nurse heard Kane say anything.

Wise answers: “That was probably my fault.”

– Edward Landler

3. Apocalypse Now

Directed by: Francis Ford Coppola

Supervising Editor: Richard Marks

Picture Editing: Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch

Supervising Sound Editor: Richard P. Cirincione

Sound Design/Montage: Walter Murch

Re-Recording Mixers: Richard Beggs, Mark Berger, Walter Murch, Thomas Scott, Dale Strumpell Music Editor: Stan Witt

Ever the contrarian, novelist Tom Wolfe commented on the legacy of the Vietnam War on a recent interview. “If you ask people who were much against that war at the time what was it that was wrong with that war, they can’t remember,” her said. They can’t remember what it was.” What Wolfe seems to be saying is that as wars fade, so do our views of them. But this seems less true of war movies; the great ones have a way of living on in our collective memory.

For example, in the 2002 Sight & Sound poll of the greatest films ever made, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, which is set during the Vietnam War and was released only a few years after it ended, was included on the lists of four critics (including Roger Ebert) and eight directors. The film’s continued popularity just may prove Wolfe’s point — in a roundabout way. After all, the work that inspired Apocalypse Now was written more than half a century before the Vietnam War.

Coppola and co-screenwriter John Milius took the story from Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness. The filmmakers could have laid the essential plot (the search for the mad Colonel Kurtz, played in the film by Marlon Brando) over almost any war, but chose the one then raging in Southeast Asia. Seen again today, there is undeniably an out-of-time feel to Apocalypse Now — even when it is superficially at its most au courant. For example, the frenzied photojournalist played by Dennis Hopper, who has been encamped with Colonel Kurtz for far too long, is usually seen as emblematic of the late 1960s, yet it is clear that Coppola biographer Peter Cowie was on to something when he compared the character to a Shakespearean fool.

The masterful editing by Walter Murch, A.C.E., Gerald B. Greenberg, A.C.E., and Lisa Fruchtman, A.C.E., overseen by supervising editor Richard Marks, A.C.E., contributes immeasurably to this timeless quality. The film is justly celebrated for its big, loud set pieces, such as the iconic napalm-strike sequence set to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.” Editorially, the film is not short on dazzling effects either, ranging from the droll juxtaposition of a recording of Colonel Kurtz talking nonsensically about snails with unappetizing shots of of a lunch of shrimp, or the unforgettable crosscutting of the murder of Kurtz with the tribal slaying of an ox. Once experienced, these sounds and images remain in the mind forever.

At the same time, it is an altogether more mysterious tone that is at the heart of this reimagining of Heart of Darkness. By the time Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) — dispatched by the Army to find and “terminate with extreme prejudice” Colonel Kurtz — has reached the deepest jungles of Cambodia via patrol boat, the film has quieted down. The becalmed tenor of these stretches of Apocalypse Now is aided by the languid rhythms of the editing, which, by this point, is anything but flashy.

“Baleful fade-outs and dream-like dissolves…contribute to the mood of the finale,” wrote Peter Cowie in his authoritative The Apocalypse Now Book in 2001. Indeed, from its opening sequence onwards, the film is replete with dissolves, each one coming at just the right moment. Appropriately enough, the cutting pattern established in the dreamy last leg of the film (shots of activity on the boat intercut with shots of the boat moving upriver, often in a smoky haze) lulls the viewer. We might even find ourselves becoming complacent as the men goof around or read letters from home.

Then something awful and unexpected will happen — like the torrent of gunfire that kills Clean (Laurence Fishburne) or the spear that pierces Chief (Albert Hall) in the heart. But even in a moment as shocking as the latter, the film does not abandon the oddly poetic air it seems to savor. On being wounded, Chief remarks, almost disbelievingly, “A spear.” The line reading has something of the plaintiveness of “Et tu, Brutus?”

Voices play a big role in Apocalypse Now. Murch (also credited with sound montage and design, as well as re- recording mixing) and his associates (including fellow re-recording mixers Mark Berger, Richard Beggs, Dale Strumpell and Thomas Scott) masterfully balance the expressionless narration spoken by Sheen with the synthesized whine of the score, which was composed by the director and his father, Carmine Coppola.

No appreciation of Apocalypse Now would be complete, of course, without acknowledging

the superlative work of music editor Stan Witt, who, along with supervising sound editor Richard Cirincione (joined by sound editors Leslie Hodgson, Les Wiggins, Pat Jackson, Maurice Schell and Jay Miracle), orchestrated the soundtrack of music and sounds that we identify so strongly with the film, such as the cue of The Doors’ “The End” over the first shot. “Having a song called ‘The End’ at the beginning of the film has its own irony,” Murch comments in The Apocalypse Now Book. “And yet there are images at the beginning that forecast the end, so it’s telegraphic in a sense.” Then there is the whisper of Brando’s voice — as unforgettable as any song. Speaking of Brando, who chillingly reads T.S. Eliot’s words on “the hollow men,” critic Ebert wrote, “That voice sets the final tone of the film.”

Even after Willard has arrived at the temple that Kurtz has taken over and commands, the introduction of Kurtz himself is beautifully delayed through the editing. He is first glimpsed reclining in darkness. Willard has been brought in to meet him. The camera moves in closer to Kurtz as he rises and begins to speak. He is then seen in close-ups (intercut with close- ups of Willard), his bald head bobbing out of the shadows until we finally see his face. It is extraordinary to behold what cinematographer Vittorio Storaro can do with a close-up. It seems clearer than ever that Kurtz can plausibly be interpreted as a kind of ghoulish heavy; the shot of his boots trudging through the mud on his way to see the captured Willard is straight out of a 1930s horror picture. It is not for nothing that Brando’s “the horror, the horror” is arguably the movie’s most famous and oft-quoted line.

What ever else we remember about the Vietnam War, we should remember what an achievement Apocalypse Now was in its day, and how much its supple editing and soundscape contribute to its haunting effect on the audience.

– Peter Tonguette

4. All That Jazz (1979)

Directed by: Bob Fosse

Picture Editing: Alan Heim

Supervising Sound Editor: Maurice Schell Re-Recording Mixer: Dick Vorisek

Music Editor: Michael Tronick

The screen is black. Coughing is heard, followed by a fade-in to a rapidly paced succession of images — an extremely close shot of an audio cassette starting to play a Vivaldi concerto then heard over a tight shot of a blood-shot eye, Alka-Seltzer fizzing in a glass, a prescription vial of Dexedrine, a goateed man (Roy Scheider) framed in a mirror next to a show poster of women’s legs, then in a shower stall, more close shots of him lighting a joint and Visine going into his red eyes, a long shot of him walking a tightrope in seemingly immense darkness, a shot through the net from below as he falls…

With this, we are immediately thrust into both the real and imaginary worlds of Joe Gideon, the central character of Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz. This tight and vigorous sequence leads to a medium shot of Joe in the bathroom mirror, dressed in black, ready to face the day, stretching out his hands to announce: “It’s showtime, folks!”

The sequence climaxes as the baroque Vivaldi segues into the song “On Broadway” on a cut to a zoom out from a theatre stage from behind Gideon directing a dense crowd of dancers through auditions for his new show. With the song playing under the following five-minute sequence, the pace of the editing continues with no loss of momentum as the painstaking process of selecting performers is brilliantly crystallized — including two bravura montages of successive jump cuts of close shots of singers and dancers performing against the same backgrounds.

Despite this dazzling display of editing flair, the Oscar-winning work of picture editor Alan Heim, A.C.E., in All That Jazz does not call attention to itself. Instead, it conveys a gut understanding of the intensity and personal politics of mounting a Broadway show while it also establishes a unique integration of visual and musical material that has influenced every movie musical since. Immersing the viewer in this archetypal show-biz story, it allows us to identify with the emotions and psychology of film and theatre director and choreographer Gideon, a character very much like his creator.

Fosse wrote the screenplay — with Robert Alan Authur — basing much of it on his own character and experiences. Fosse’s efforts to stage the original Broadway production of Chicago while finishing his movie Lenny (1974) with Dustin Hoffman as Lenny Bruce, his marriage to Gwen Verdon, his notorious womanizing and his own open-heart surgery are all woven together in Gideon’s story. In the film, Ann Reinking even plays a character with the same long-term intimate relationship to Gideon as she had with Fosse.

In another borrowing from reality, All That Jazz — from the title of the song in Chicago — has Gideon finishing editing a Lenny-like movie called Stand Up about a Bruce-like comedian. Giving a nicely understated performance as Eddie, Stand Up’s editor, is Lenny’s editor: Heim himself doing double duty on the job.

Cut in throughout Gideon’s day-to- day reality in All That Jazz are his fantasy dialogues in an ever-changing night club- bish dark place with his imaginary Angel of Death — Angelique, played by Jessica Lange. At first, these scenes are cut in to indicate Gideon feeling the symptoms of his heart condition, but they evolve into a continuing interior monologue revealing his fear and sense of guilt. The carefully timed cutting in of these personal fantasies add resonance to his exterior reality and serve to introduce flashbacks without confusing viewers. These dreams are always cut in — sometimes only to register as a brief image — but when one such image comes as a dissolve, it makes a significant impact, emotionally and thematically.

Heim told CineMontage that Fosse had written the script with the intention of doing this kind of cross-cutting. “By writing a certain structure into it, he limited the flexibility in the cutting.” Heim said, adding, “Nothing went out of the editing room without being in Bob’s mind.”

Still, Heim’s sense of timing and rhythm consistently bolsters Fosse’s dramatic intentions. The masterfully choreographed musical numbers alone — both real and imaginary — are equally dynamic works of editing, but Heim brings the same precision to key dramatic scenes like the cast’s read-through of the play while Gideon struggles with his physical pain. During this sequence, the viewer (like Gideon) sees but does not hear the actors’ line readings and laughter. Cutting to close shots of his movements and actions — grabbing a cigarette out of a pack and tapping it, later stubbing it out, breaking a pencil — we hear only those sounds that he creates, along with his labored, shallow breathing.

The integration of sound in this scene and throughout the movie also contributes to the viewer’s critical sense of immersion in Joe Gideon’s personal experience. Re- recording mixer Dick Vorisek turns the exceptional work of the sound editing team — Stan Bochner, Jay Dranch, Bernard Hajdenberg and Sanford Rackow, working with supervising sound editor Maurice Schell — into a richly textured aural palette.

The ambient sounds — down to the rustles of the dancers’ clothes — and varying resonances of theatre, apartment, hospital, city streets and Gideon’s imagined trysts with Angelique all serve to build on the emotional framework underscored by the music. Music editor Michael Tronick’s work with Ralph Burns’ and Arnold Gross’ arrangements, recorded and mixed by Glenn Berger, comes across as the very heartbeat that the life of Gideon revolves around — all the way to the film’s closing with Ethel Merman heard belting out “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

Prior to Lenny, Heim first worked with Fosse on the 1972 TV show of Liza Minnelli’s stage concert, Liza with a Z, shot on film with eight cameras. After All That Jazz, he also edited Fosse’s next and last film, Star 80 (1983). Fosse has been quoted as saying Heim was “my collaborator and my conscience.” Viewing All That Jazz, this description seems justified as we experience Fosse’s alter ego traveling to where there is no heaven and no hell…but

only death.

– Edward Landler

5. Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Directed by: Arthur Penn

Picture Editing: Dede Allen

Re-Recording/Scoring Mixer: Dan Wallin (uncredited)

In Nat Segaloff’s 2011 biography, Arthur Penn: American Director, picture editor Dede Allen, A.C.E., is quoted as saying, “Bonnie and Clyde had a pace and a tempo that could never go the opposite way. It carried you along at such a pitch that you were never let down, even for a generation that’s been raised in a different tempo. It was the most finely honed picture I ever worked on.”

In recognition of Allen’s contribution to Penn’s film, Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 marked the first time an editor received a solo opening credit on a film. Editor Craig McKay, A.C.E., worked with Allen on a number of feature films. “One of the things Dede always said to me was, ‘Never let the audience get ahead of the story,’” recalled McKay in a 2010 interview on NPR. “That was a staunch belief of hers. And she would do things like never use a useless shot; every shot gave you new information. And very often, she cut with a staccato rhythm to move things along. Those kind of elements, which weren’t really followed traditionally, were what she brought to the art.” To achieve this rapidly paced tempo in driving the story forward, Allen would frequently say, “You have to cut with your gut.”

Another finely honed technique Allen used to achieve Bonnie and Clyde’s breakneck pace was cutting on action, unexpectedly, while actions onscreen are still taking place. This technique hurls the narrative along, frenetically driving one shot into the next. It was a tempo that Penn appreciated. Bonnie and Clyde would be the first of six subsequent feature film collaborations between Allen and Penn.

“Dede is a wonderful collaborator,” Penn told Segaloff. “She understands what an actor is doing, so my whole theory about rhythm is a theory that she shares.” Penn also noted Allen’s dogged persistence in working with a scene until it is finely tuned for finish. “She is daunting,” Penn declared. “She will stay even with something small until it works, until it’s right. I will say, ‘Okay, that’s enough, let’s leave it alone,’ and then I’ll come back in the editing room the next day and it will be totally different, and I’ll say, ‘When did you do that?’ And she’ll say, ‘Oh, I stayed here all night last night working on it.’”

An additional technique that Allen perfected on Bonnie and Clyde was making sound precede picture with “pre-lapping.” Observed McKay, “Some of that had been done, but traditionally, it’s a word or two. Dede was not afraid to do a sentence, and not only just dialogue but other sounds — anything to keep moving the narrative forward.”

The sound editing on Bonnie and Clyde was as innovative as the picture assembly, although it was uncredited. Also uncredited was Dan Wallin, the re- recording and scoring mixer on the film. Wallin worked on over 500 films and was nominated for the Academy Award numerous times. The collision of unlikely sounds, the frenetic guitar and banjo of Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, the whoopin’ and hollerin’, gunshots, squealing rubber and the persistent shrieking of Estelle Parson’s character was unprecedented. Quietness, too, accentuated with the rustling of leaves in the wind, or gentle birdcalls, was unexpectedly used for emotional juxtaposition and as a foreshadowing of the lovers’ doom.

With sound effects, dialogue and music overlapping, and sometimes preceding a kinetic mosaic of rapid cuts between a variety of shots, mixing slow motion with regular film speeds, and in general disrupting the temporal order, it’s no surprise that many film critics were taken by surprise, unsure of what to make of these innovations. Among them was Bosley Crowther, veteran film critic at The New York Times, who characterized Bonnie and Clyde as “a cheap piece of bald- faced slapstick that treats the hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cut-ups in Thoroughly Modern Millie.”

One of the sound and image juxtapositions that particularly troubled critics was Scruggs’s banjo playing over scenes of gunfire and violence. And the violence, which Penn acknowledged should be a shock to the audience, set a new high- water mark in commercial cinema. One violent scene, in particular, marked a tonal shift in the narrative of Bonnie and Clyde, as well as cinema itself.

As the outlaw pair flee the scene of a bank robbery, a clerk jumps on the running board of their car, only to be shot in the face through the window glass by Clyde (Warren Beatty). “It used to be that you couldn’t shoot somebody and see them hit in the same frame,” Penn told film historian Peter Biskind. “There had to be a cut. We said, ‘Let’s not repeat what the studios have done for so long. It has to be in-your- face.’” The ambush scene, in which the outlaws perish in slow motion under a hail of gunfire from lawmen, marked a new level of violence in cinema. The climax is magnificently put together with editing that quietly sets the stage for the horrific massacre that follows. With this finale, Penn said that he wanted “to take the film away from the relatively squalid quality of the story into something a little more balletic. I wanted closure.”

The ambush scene was a challenge to edit. It had been shot over three days at Albertson Ranch in Triunfo, California in December 1966. Multiple cameras were set to film the ambush, running at different speeds, some with a very high frame rate to slow the action down. Penn ganged the cameras from one position to reflect a common point of view. “I didn’t want us to jump around,” he said. Because of the multiple cameras and varying frame rates, there wasn’t time to get up to speed and to slate the cameras.

Allen’s assistant Jerry Greenberg had initially been given the task of cutting the ending. “He kept trying to make sense of it,” said Penn. “He was trying to cut it literally. But then Dede — she’s tremendous — says, ‘Okay, now let’s go to work. We know what to do.’”

Allen’s work on Bonnie and Clyde redefined the importance, and the creative status, of the editor in motion pictures. Her innovations on Bonnie and Clyde have now become standard usage in the grammar of motion picture editing.

– Ray Zone

6. The Godfather (1972)

Directed by: Francis Ford Coppola Picture Editing: William Reynolds, Peter Zinner Sound Effects Editor: Howard Beals (uncredited) Re-Recording Mixers: Charles Grenzbach, Richard Portman Music Editor: John C. Hammell

7. Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Directed by: David Lean Picture Editing: Anne V. Coates Sound Editors: Winston Ryder, Malcolm Cooke (uncredited) Sound Dubbing: John Cox

8. Jaws (1975)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg Supervising Sound Editors: John Stacy, James Troutman, Colin C. Mouat Picture Editing: Verna Fields Sound Editors: George Fredrick, Colin C. Mouat, Roger Sword, James Troutman (all uncredited) Sound: Robert L. Hoyt, Earl Madery, Roger Heman, Jr. (uncredited) Music Editor: Joseph Glassman (uncredited)

9. JFK (1991)

Directed by: Oliver Stone

Picture Editing: Joe Hutshing, Pietro Scalia Supervising Sound Editors: Wylie Stateman, Michael D. Wilhoit Re-Recording Mixers: Gregg Landaker, Michael Minkler Music Editor: Kenneth Wannberg

10. The French Connection (1971)

Directed by: William Friedkin Picture Editing: Gerald B. Greenberg Sound: Theodore Soderberg

11. The Conversation (1974)

Directed by: Francis Ford Coppola Supervising Editor: Walter Murch Picture Editing: Richard Chew Sound Montage: Walter Murch Sound Effects Editor: Howard Beals (uncredited) Sound Re-Recording: Walter Murch

12. Psycho (1960)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock Picture Editing: George Tomasini

13. The Battleship Potemkin (1925)

Directed by: Sergei M. Eisenstein Picture Editing: Sergei M. Eisenstein (uncredited)

14. Memento (2000)

Directed by: Christopher Nolan Picture Editing: Dody Dorn Supervising Sound Editors: Gary S. Gerlich, Richard LeGrand, Jr. Re-Recording Mixers: Michael C. Casper, Jonathan Wales Music Editor: Mikael Sandgren

15. Goodfellas (1990)

Directed by: Martin Scorsese Picture Editing: Thelma Schoonmaker Supervising Sound Editor: Skip Lievsay Re-Recording Mixer: Tom Fleischman Music Editor: Christopher Brooks

16. Star Wars (1977)

Directed by: George Lucas Picture Editing: Richard Chew, Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas Supervising Sound Editor: Sam Shaw Special Dialogue and Sound Effects: Ben Burtt Re-Recording Mixers: Les Fresholtz, Robert J. Litt, Don MacDougall, Bob Minkler, Michael Minkler, Richard Portman, Ray West Supervising Music Editor: Kenneth Wannberg

17. City of God (Cidade de Deus) (2002)

Directed by: Fernando Meirelles Picture Editing: Daniel Rezende Sound Designer: Martín Hernández Sound Editor: Pradip Romay Re-Recording Mixer: Rudy Pi

18. Pulp Fiction (1994)

Directed by: Quentin Tarantino Picture Editing: Sally Menke Supervising Sound Editor: Stephen Hunter Flick Re-Recording Mixers: Rick Ash, Dean A. Zupancic Music Editor: Rolf Johnson

19. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Directed by: Stanley Kubrick Picture Editing: Ray Lovejoy Sound Supervisor: A.W. Watkins

Chief Dubbing Mixer: J.B. Smith Music Editor: Frank J. Urioste (uncredited)

20. Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Directed by: Sidney Lumet Picture Editing: Dede Allen Sound Editors: Richard P. Cirincione, Jack Fitzstephens, Sanford Rackow, Stephen A. Rotter Sound Re-Recording Supervisor: Dick Vorisek

City of God. Miramax21. Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg Picture Editing: Michael Kahn Supervising Sound Effects Editor: Richard L. Anderson Supervising Dialogue Editor: Curt Schulkey Sound Designer: Ben Burtt

Sound Re-Recordists: Steve Maslow, Bill Varney Music Editor: Kenneth Wannberg

22. The Godfather Part II (1974)

Directed by: Francis Ford Coppola Picture Editing: Barry Malkin, Richard Marks, Peter Zinner

Sound Montage: Walter Murch Sound Effects Editors: Howard Beals, James Fritch, James J. Klinger

Sound Re-Recording: Walter Murch Music Editor: George Brand

23. The Wild Bunch (1969)

Directed by: Sam Peckinpah Picture Editing: Lou Lombardo Supervising Sound Effects Editor: Ed Scheid (uncredited) Sound Re-Recording/Scoring Mixer: Dan Wallin (uncredited) Supervising Music Editor: Richard C. Harris (uncredited)

24. Saving Private Ryan (1998)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg Picture Editing: Michael Kahn Supervising Sound Editor: Richard Hymns Re-Recording Mixers: Andy Nelson, Gary Rydstrom, Gary Summers Music Editor: Kenneth Wannberg

25. The Matrix (1999)

Directed by: Andy Wachowski, Lana Wachowski Picture Editing: Zach Staenberg

Supervising Sound Editor: Dane A. Davis Re-Recording Mixers: David E. Campbell, Kevin E. Carpenter, John T. Reitz, Gregg Rudloff Music Editors: Lori L. Eschler, Zigmund Gron, Jordan Corngold (uncredited)

26. Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Directed by: Jonathan Demme Picture Editing: Craig McKay

Sound Designer: Skip Lievsay Re-Recording Mixer: Tom Fleischman Music Editor: Suzana Peric

27. Breathless (À bout de soufflé) (1960)

Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard Picture Editing: Cécile Decugis, Lila Herman Sound: Jacques Maumont

28. Fight Club (1999)

Directed by: David Fincher Picture Editing: James Haygood Supervising Sound Editor: Richard Hymns Sound Designer: Ren Klyce Re-Recording Mixers: Todd Boekelheide, David Parker, Michael Semanick

Music Editor: Brian Richards

29. Requiem for a Dream (2000)

Directed by: Darren Aronofsky Picture Editing: Jay Rabinowitz Supervising Sound Editor: Nelson Ferreira Sound Designer: Brian Emrich Re-Recording Mixers: Tom Johnson, Tony Sereno

Music Editors: Stephen Barden, Matt Mayer, Jay Rabinowitz

Cabaret. Allied Artists30. Cabaret (1972)

Directed by: Bob Fosse Picture Editing: David Bretherton Supervising Sound Editor: James Nelson (uncredited) Dubbing: Robert Knudson, Arthur Piantadosi Music Editors: Illo Endrulat, Karola Storr, Robert Tracy

31. Chinatown (1974)

Directed by: Roman Polanski Picture Editing: Sam O’Steen Sound Editors: Bob Cornett, Howard Beals (uncredited), Roger Sword (uncredited) Re-Recording Mixers: David Dockendorf (uncredited), John Wilkinson (uncredited) Music Editor: John C. Hammell

32. Moulin Rouge! (2001)

Directed by: Baz Luhrmann Picture Editing: Jill Bilcock Sound Supervisor: Roger Savage Supervising Sound Effects Editor: Brent Burge Supervising Dialogue Editor: Antony Gray Re-Recording Mixers: Anna Behlmer, Andy Nelson, Roger Savage Supervising Music Editor: Simon Leadley

33. Seven Samurai (1954)

Directed by: Akira Kurosawa Picture Editing: Akira Kurosawa Sound Effects Editor: Ichirô Minawa

34. Casablanca (1942)

Directed by: Michael Curtiz Picture Editing: Owen Marks Sound: Francis J. Scheid

35. Inception (2010)

Directed by: Christopher Nolan Picture Editing: Lee Smith Supervising Sound Editor: Richard King Sound Designer: Richard King Re-Recording Mixers: John P. Fasal, Lora Hirschberg, Gary Rizzo Supervising Music Editor: Alex Gibson

36. Rope (1948)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock Picture Editing: William H. Ziegler Sound: Al Riggs

37. Schindler’s List (1993)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg Picture Editing: Michael Kahn Supervising Sound Editors: Charles L. Campbell, Louis L. Edemann Re-Recording Mixers: Scott Millan, Andy Nelson, Steve Pederson Music Editor: Kenneth Wannberg

38. West Side Story (1961)

Directed by: Jerome Robbins, Robert Wise Picture Editing: Thomas Stanford

Sound Supervisor: Gordon Sawyer (uncredited) Music Editor: Richard Carruth

39. The Fugitive (1993)

Directed by: Andrew Davis Picture Editing: Don Brochu, David Finfer, Dean Goodhill, Dov Hoenig, Richard Nord, Dennis Virkler Supervising Sound Editors: John Leveque, Bruce Stambler Re-Recording Mixers: Michael Herbick, Donald O. Mitchell, Frank A. Montaño Music Editor: Jim Weidman

40. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Directed by: Stanley Kubrick Picture Editing: Bill Butler Sound Editor: Brian Blamey Dubbing Mixers: Eddie Haben, Bill Rowe

41. 81⁄2 (1963)

Directed by: Federico Fellini Picture Editing: Leo Cattozzo Sound: Alberto Bartolomei, Mario Faraoni

42. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

Directed by: Milos Forman Supervising Film Editor: Richard Chew Picture Editing: Sheldon Kahn, Lynzee Klingman Post-Production Sound Director: Mark Berger Music Editor: Ted Whitfield

43. Reds (1981)

Directed by: Warren Beatty Picture Editing: Dede Allen, Craig McKay Supervising Sound Editor: Richard P. Cirincione Sound Re-Recording Mixers: Tom Fleischman, Dick Vorisek Music Editors: Michael Tronick, Ted Whitfield

44. The Shining (1980)

Directed by: Stanley Kubrick Picture Editing: Ray Lovejoy Sound Editors: Dino Di Campo, Jack T. Knight, Winston Ryder (uncredited) Dubbing Mixer: Bill Rowe

45. Days of Heaven (1978)

Directed by: Terrence Malick Picture Editing: Billy Weber Sound Effects Editors: Charles L. Campbell, Colin C. Mouat Sound Re-Recording Mixer: John Wilkinson Sound Effects Mixer: John T. Reitz Music Editors: Daniel Allan Carlin, Ted Roberts

46. Ben-Hur (1959)

Directed by: William Wyler Picture Editing: John D. Dunning, Ralph E. Winters

Co-Supervising Sound Editor: Van Allen James (uncredited) Recording Supervisor: Franklin Milton

47. Vertigo (1958)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock Picture Editing: George Tomasini Sound Editors: George Dutton (uncredited), Bill Wistrom (uncredited) Music Editor: Leon Birnbaum (uncredited)

Shown foreground: Charlton Heston (as Judah Ben-Hur)

48. Apollo 13 (1995)

Directed by: Ron Howard Picture Editing: Dan Hanley, Mike Hill Supervising Sound Editor: Stephen Hunter Flick Re-Recording Mixers: Bob Chefalas, Rick Dior, Ezra Dweck, Scott Millan, Steve Pederson Supervising Music Editor: Jim Henrikson

49. Rear Window (1954)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock Picture Editing: George Tomasini Sound Editor: Howard Beals (uncredited) Sound Recording Mixer: Loren L. Ryder (uncredited)

50. Touch of Evil (1958)

Directed by: Orson Welles Picture Editing: Aaron Stell, Virgil W. Vogel, Edward Curtiss (uncredited) Sound Editors: Peter Berkos (uncredited), Robert L. Bratton (uncredited)

51. Living Russia (1929) (The Man with a Camera)

Directed by: Dziga Vertov Picture Editing: Dziga Vertov

52A. The Graduate (1967)

Directed by: Mike Nichols Picture Editing: Sam O’Steen Sound: Jack Solomon

52B. Out of Sight (1998)

Directed by: Steven Soderbergh Picture Editing: Anne V. Coates

Supervising Sound Editor: Larry Blake Re-Recording Mixers: Larry Blake, Gerry Lentz

54. High Noon (1952)

Directed by: Fred Zinnemann Editorial Supervisor: Harry Gerstad Picture Editing: Elmo Williams Sound: Jean L. Speak, John Speak (uncredited) Music Editor: George C. Emick

55. Black Hawk Down (2001)

Directed by: Ridley Scott Picture Editing: Pietro Scalia Supervising Sound Editors: Karen M. Baker, Per Hallberg Re-Recording Mixers: Michael Minkler, Myron Nettinga, Gary Rizzo

Music Editor: Marc Streitenfeld

56. Titanic (1997)

Directed by: James Cameron Picture Editing: Conrad Buff, James Cameron, Richard A. Harris

Supervising Sound Editor: Tom Bellfort Re-Recording Mixers: Christopher Boyes, Lora Hirschberg, Tom Johnson, Ronald G. Roumas, Gary Rydstrom Supervising Music Editor: Jim Henrikson

57. The Limey (1999)

Directed by: Steven Soderbergh Picture Editing: Sarah Flack Supervising Sound Editor: Larry Blake Re-Recording Mixers: Larry Blake, Melissa Sherwood Hofmann

58. The Exorcist (1973)

Directed by: William Friedkin Picture Editing: Norman Gay, Evan A. Lottman Supervising Sound Editor: James Nelson (uncredited) Dubbing Mixer: Buzz Knudson Music Editor: Eugene Marks

59. Annie Hall (1977)

Directed by: Woody Allen Picture Editing: Wendy Greene Bricmont, Ralph Rosenblum

Sound Editors: Dan Sable, William S. Scharf (uncredited) Re-Recording Mixer: Jack Higgins

60. Rashômon (1950)

Directed by: Akira Kurosawa Picture Editing: Akira Kurosawa

61A. Sherlock, Jr. (1924)

Directed by: Buster Keaton Picture Editing: Buster Keaton (uncredited)

61B. Speed (1994)

Directed by: Jan de Bont Picture Editing: John Wright Supervising Sound Editor: Stephen Hunter Flick Re-Recording Mixers: Bob Beemer, Gregg Landaker, Steve Maslow

63. L.A. Confidential (1997)

Directed by: Curtis Hanson Picture Editing: Peter Honess Supervising Sound Editor: John Leveque Re-Recording Mixers: Anna Behlmer, Andy Nelson Music Editors: Kenneth Hall, Paul Rabjohns, Sally Boldt (uncredited)

64. The Sound of Music (1965)

Directed by: Robert Wise Picture Editing: William Reynolds Sound Editor: Don Stern (uncredited) Music Editor: Robert Mayer

65. The Tree of Life (2011)

Directed by: Terrence Malick Picture Editing: Hank Corwin, Jay Rabinowitz, Daniel Rezende, Billy Weber, Mark Yoshikawa Supervising Sound Editor: Craig Berkey Co-Supervising Sound Editor: Erik Aadahl Supervising Re-Recording Mixer: Craig Berkey Music Editors: Dick Bernstein, Peter Clarke

66. The Bourne Ultimatum (2007)

Directed by: Paul Greengrass Picture Editing: Christopher Rouse Supervising Sound Editors: Karen Baker Landers, Per Hallberg Re-Recording Mixers: Bob Beemer, Scott Millan, David Parker

Supervising Music Editor: Thomas A. Carlson

67. Z (1969)

Directed by: Costa-Gavras Picture Editing: Françoise Bonnot Sound Editor: Michèle Boëhm

Sound Engineers: Jean Nény, Alex Pront

68. A Hard Day’s Night (1964)

Directed by: Richard Lester Picture Editing: John Jympson Sound Editors: Gordon Daniel, Jim Roddan (uncredited)

69A. Hugo (2011)

Directed by: Martin Scorsese Picture Editing: Thelma Schoonmaker Supervising Sound Editor: Philip Stockton Co-Supervising Sound Editor: Eugene Gearty Re-Recording Mixer: Tom Fleischman Supervising Music Editor: Jennifer L. Dunnington

69B. Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Directed by: John Schlesinger Picture Editing: Hugh A. Robertson

Sound Editors: Vincent Connelly, Jack Fitzstephens Sound Mixer: Dick Vorisek

69C. Miller’s Crossing (1990)

Directed by: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen (uncredited) Picture Editing: Michael R. Miller

Supervising Sound Editor: Skip Lievsay Re-Recording Mixer: Lee Dichter Music Editor: Todd Kasow

72. Blade Runner (1982)

Directed by: Ridley Scott Supervising Editor: Terry Rawlings Picture Editing: Marsha Nakashima Sound Editor: Peter Pennel Re-Recording Mixers: Joel Fein, John Hayward, Nicolas Le Messurier (all uncredited)

73. Mulholland Dr. (2001)

Directed by: David Lynch Picture Editing: Mary Sweeney Supervising Sound Editor: Ronald Eng Sound Designer: David Lynch Re-Recording Mixers: Ronald Eng, Patrick Giraudi, David Lynch, John Neff Music Editor: John Neff

74. Rocky (1976)

Directed by: John G. Avildsen Picture Editing: Scott Conrad, Richard Halsey Post-Production Sound: Ray Alba, Bert Schoenfeld Sound: Harry W. Tetrick Music Editor: Joe Tuley

75. North by Northwest (1959)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock Picture Editing: George Tomasini Supervising Sound Editor: Van Allen James (uncredited) Recording Supervisor: Franklin Milton