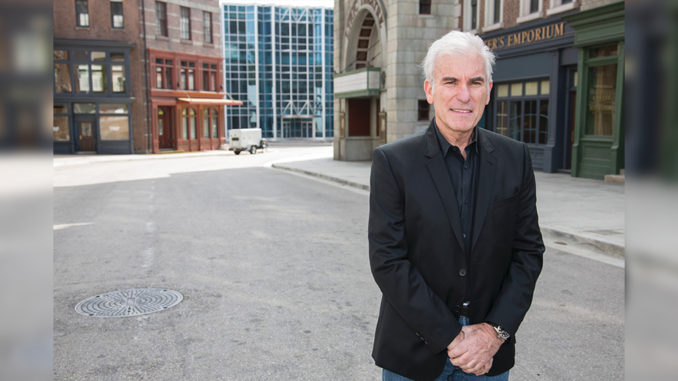

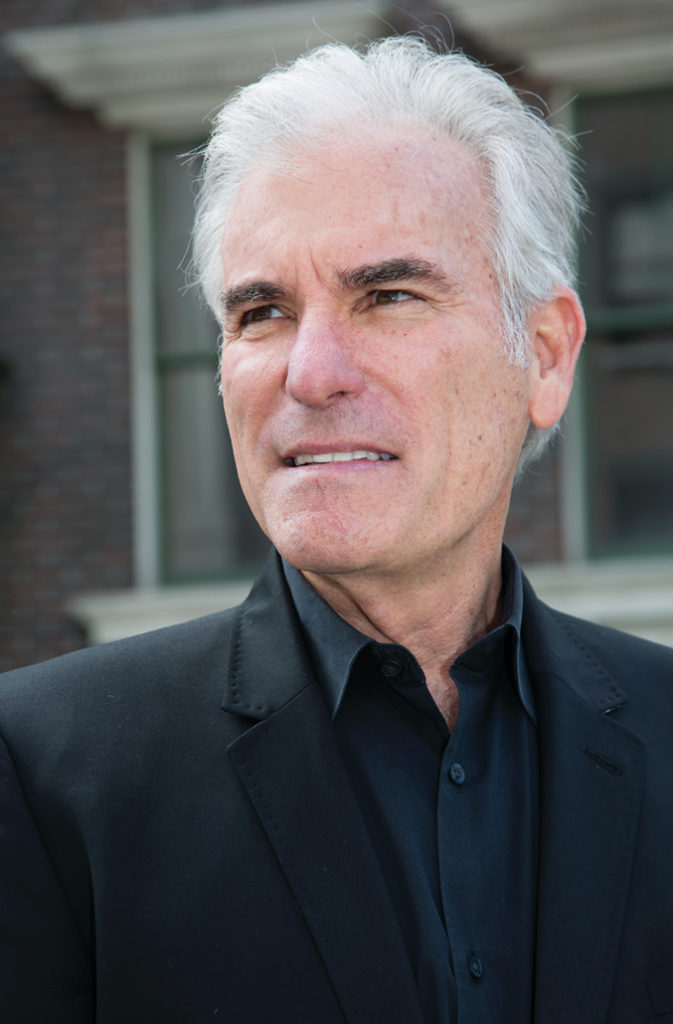

by Peter Tonguette • portraits by Deverill Weekes

Michael Tronick, A.C.E., has to stop and pinch himself when he thinks about the people he has encountered in the more than two decades he’s worked as an editor on such films as Midnight Run (1988), Days of Thunder (1990) and True Romance (1993). He has had multi-film collaborations with directors Martin Brest and Tony Scott, and his list of editing mentors includes some of the best in the profession. He was one of the editors who helped craft Al Pacino’s Oscar-winning performance in Scent of a Woman (1992). He has even ridden in Mick Jagger’s limousine.

Yet Tronick, a Los Angeles native, did not consider entering the movie business until he was an undergraduate at UCLA. “I was a political science major,” he says. “I thought I was going to go to law school.” It took a brush with student filmmaking — and a near miss with the Vietnam War — to convince him to rethink his plans. “Honestly, I came within an eyelash of being drafted and going into the Army,” he recalls. “It was kind of a wake-up call as far as what I really wanted to do.”

Making his path even more unlikely is the fact that for the first 10 years of his career, Tronick was not a film editor at all, but a music editor on the rise. After attending graduate school at San Francisco State University, where he studied film, Tronick worked at Gene McCabe Productions, a maker of industrial films. It was an early eye-opener for him. “I’d gone from an idealistic undergraduate student to working for a multi-national corporation that burns up the environment,” he laughs. “But it was there that I really got my exposure to production. I did everything from picking up my boss’ dry cleaning to assistant camera, camera operator, gofer, grip, everything.”

More significantly, it was at McCabe that Tronick met music editor Dan Carlin, Sr., who introduced him to the field and provided some key breaks. He remembers that Carlin, a frequent collaborator of director Sam Peckinpah and composer Jerry Fielding, took him “from the new Chrysler Cordoba to a dubbing stage watching Sam mix The Killer Elite [1975].” By the early 1980s, Tronick had established himself as an in-demand music editor, with credits including All That Jazz (1979), 48 Hrs. (1982) and A Chorus Line (1985).

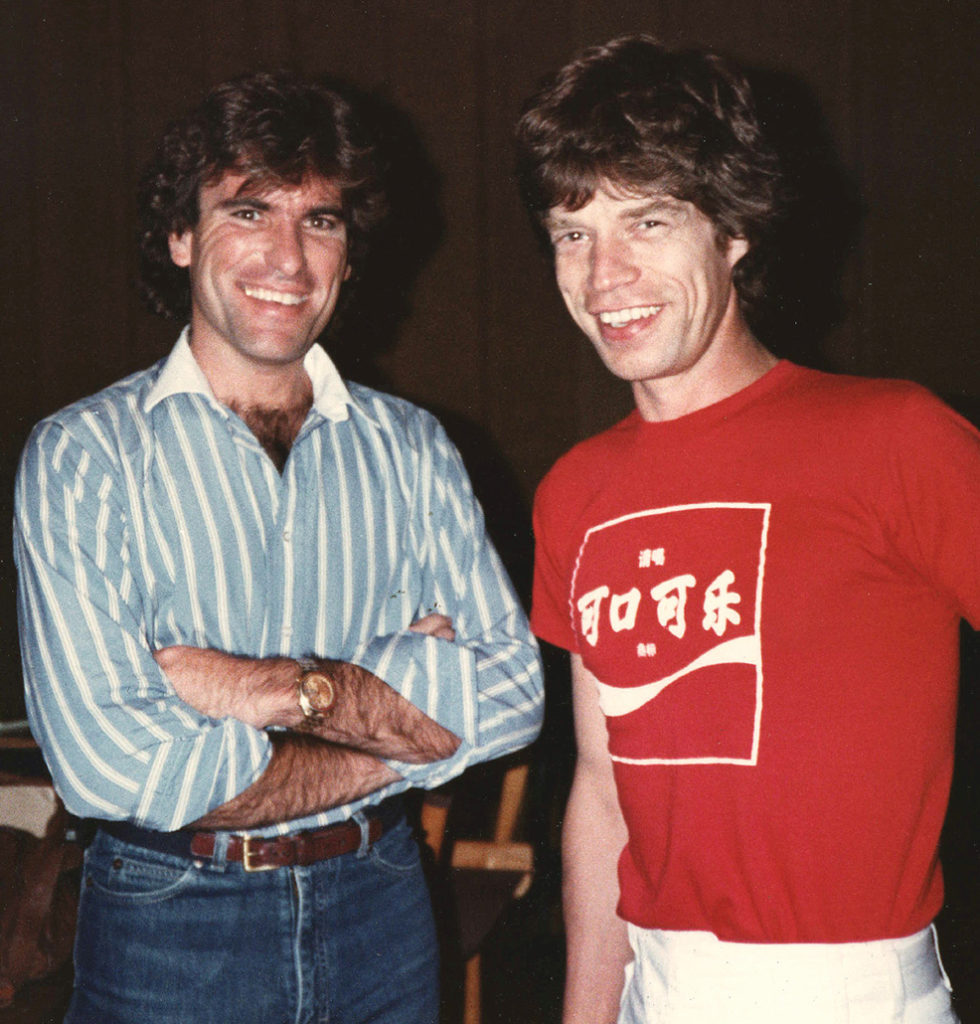

Mick Jagger during the

making of Let’s Spend the Night Together in 1982.

Courtesy of Michael Tronick

He got his first taste of picture editing when he was invited to work on musical sequences, first on a film he was music editing — Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984), edited by Freeman Davies, Jim Coblentz and Michael Ripps, A.C.E. — and then on Disney’s made-for-TV movie Double Switch (1987), edited by John Wright, A.C.E. Not long after, Billy Weber came calling. “I’ll put Billy on my Mount Olympus of mentorship,” Tronick says. “He was cutting Beverly Hills Cop II [1987] for Tony Scott, and he asked me to be the third editor. That was my first job exclusively as a picture editor without cutting music.”

Tronick’s latest film, 2 Guns, stars Denzel Washington and Mark Wahlberg as undercover agents with the DEA and Naval Intelligence, respectively, who are entrapped by their organizations as they pursue drug cartels in Mexico. Icelandic director Baltasar Kormakur’s film, to be released by Universal Pictures August 2, is the latest in a series of action comedies in which the editor has come to specialize, including Midnight Run (1988), one of his three collaborations with Martin Brest, and Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005).

“I think one of the reasons I got the gig on 2 Guns was because of those types of films,” Tronick comments. It was just one more stroke of good luck in his fortuitous career. CineMontage spoke with him as he was finishing work on 2 Guns with longtime assistants Aaron Brock and Jill Piwowar, and apprentice Bryan Torres.

CineMontage: As you were starting out, it doesn’t sound like you ever said to yourself, “Music editing is for me.”

Michael Tronick: I was a musician as a kid. I wasn’t particularly good, but I could read. I played in bands and orchestras in school, and then had a little bit of a rock ‘n’ roll fling at UCLA as a drummer. So I could appreciate the musicianship. Going to my first scoring session was just an amazing experience in terms of the caliber of musicians and hearing music being played to a scene. It was very seductive. To be a part of that world was very appealing to me.

CM: How has the job of music editing changed since you began?

MT: There are principles that are still the same, but the job itself has changed drastically. Temp scores started coming into popularity toward the end of my music editing career, and now that’s a given on any project. I cut mag and worked on musicals and had separate vocal mag, dance Foley and orchestra. We were not able to see line forms of an audio plot to know exactly where the cut was; you just had to hit the brake on the Moviola or the KEM, mark it with a grease pencil and make your splice there. In terms of sensibilities and aesthetics, especially when creating a temp score, all music editors have to have that awareness and sensitivity of what best enhances the story and how that’s supported by music.

So as far as the foundation, music editing probably hasn’t changed that much, but as far as the tools, it’s amazing. For me [as an editor], it’s like working with visual effects people. I can ask for anything, and usually they can do it. Music editors today are so brilliant. I’m glad I got out when I did; there’s no way I could compete with them.

There’s also the principle of communicating with composers, because you don’t want to be cutting up their music without them aware of changes made on a dubbing stage. Clinton Shorter is the composer on 2 Guns, and he came for a playback. Chuck Inouye, the music editor, would communicate to Clinton what we were doing so he was aware of delaying a cue or starting it later or doing something different. It’s almost like a first cut; you don’t want to mess with the script that much.

CM: You must have savored the chance to work with a wide variety of filmmakers, from Stanley Donen to Bob Fosse.

MT: A lot of it was just being at the right place at the right time. There weren’t a lot of music editors in New York when I first went back there. You’d run into people, who’d say, “Oh, you’re a music editor from California!” That’s how I met Dede Allen. I’ll never forget the call I got to go back and work on Reds [1981]. I still get star-struck. I just remember walking onto the dubbing stage and saying to myself, “My God, that’s Warren Beatty, movie star.” But I had to shake his hand and do my job. That was really kind of a golden period of extraordinary filmmakers. From my perspective — and this is no slight to anyone else — but I’d put Fosse at the top of the list.

Courtesy of Universal Pictures

CM: Tell me about that collaboration.

MT: It was largely due to my relationship with Ralph Burns, who was the composer on Donen’s Movie Movie (1978), and was Bob’s orchestrator/composer on all his Broadway shows; he had done Cabaret (1972) and Lenny (1974). They needed a music editor for All That Jazz and Ralph called me. It was only supposed to be two weeks in New York, and then come back and do the post in LA. One thing that stands out in my recollection of Bob is his dislike for the West Coast. Since Ralph and I were the only ones from California, all the post was done in New York. Bob had that rare gift of getting results out of me that I didn’t think I was capable of. I had only done one musical before, and All That Jazz was a really complicated film. You have to remember that I cut this music on a two-headed Moviola, too.

Bob was a lot like Joe Gideon, the Roy Scheider character in All That Jazz. There was just a twinkle in his eye, even when he had the Camel cigarette drooping from his mouth, his shirt open, wearing black. I was the guy from California. He was always teasing me about why I wasn’t wearing more gold chains! But he knew I was there to support Ralph.

CM: Reds is notable for composer Stephen Sondheim’s score.

MT: I came on to help out Ted Whitfield, who was the music editor of record who started it. Everyone had been on that movie for years. I overlapped with Ted, who then graciously bowed out. By then, Sondheim had already done his themes. I remember the very evocative piano theme that Sondheim recorded; it was recorded on a little boom box in his apartment, where he just hit record, and played it for Warren on a cassette. That was transferred into mag and placed in those specific sections in the movie. Sondheim tried to re-record it, Dave Grusin came on and recorded it, as did some of the best pianists in New York. But that original cassette recording is the music that’s in the movie; Beatty never found something he liked as much. Talk about demo love. There was something in the intonation and the inflection that emotionally no one else could duplicate — not even Sondheim himself.

CM: What can you say about working with Hal Ashby — himself a former film editor — on his 1982 Rolling Stones concert film Let’s Spend the Night Together?

MT: That was an amazing experience. We worked at cutting rooms right across the street from the Malibu Pier. Hal was a night guy, so we worked a lot of nights. I would be going home when people were coming to the beach! Hal was about as passionate about a film as you can imagine. He would sit at the KEM with editor Lisa Day. I could see that he had developed relationships with every member of the band. Of course, you got one of the greatest showmen in the world in Mick Jagger as your lead. Caleb Deschanel shot it — it looked gorgeous — and Lisa did a great job editing.

One time, on a KEM, Hal was running a song, and a splice accidentally came apart and tore the work picture. He stood up and threw the splicer; he was so upset because he loved the shot that he tore and realized that a reprint would never be the exact same color density and contrast as that one print he had of the movie. I respected him for that.

I went to England to record some overdubs for the film, and Mick would pick me up in his limo and drive me out to Olympic Studios where they recorded. I’d be in a control room, and I’d have to make a request to bassist Bill Wyman to do a little phrase in the song “Miss You” that Hal liked, but Bill said, “Well, I would never play it there.” And I had to say, “I know, but if you could just do that for Hal.” So there I was giving instruction to Bill Wyman!

CM: The first film you worked on as a film editor only was Beverly Hills Cop II in 1987.

MT: I didn’t start at the beginning. Billy and Chris [Lebenzon] saved the scenes for me that they didn’t want to cut; “Let Tronick have that one!” My first meeting with Tony Scott was the first time he came in to review my work, and I was more than a little nervous. This was the first scene I had cut, and I actually cut the tail of one shot to the head so when it came up on the KEM, it played upside down. He said, “Oh, that’s the Australian cut.” He put me right at ease. That was shot in ’scope, and I remember my first edit was from a wide shot to a close-up of Brigitte Nielsen being pulled over by a policeman in Beverly Hills. I played my cut — just one splice — and I just said, “Wow, that looks like a movie.”

CM: You worked on three films with Martin Brest, who is known for shooting a lot of footage.

MT: He is amazingly detail-oriented. He’s kind of a tortured soul in that making choices are very difficult for him. With Midnight Run, there’d be takes where we’d have to decide between, “Look what De Niro does in this take, but then look what he does in that take. So if we use that take, we can’t use this one.” This was pre-digital; it would be just a matter of examining things and whittling things down. And as much as Fosse and Burns taught me how to listen, I think Marty gave me a visual sense in terms of observing performance.

CM: What interested you in 2 Guns?

MT: When I read the script, I thought it was clever and smart; it wasn’t overtly by the numbers. An audience really has to pay attention to it. I like a film that’s not going to insult your intelligence and spell everything out for you, but lets you fill in the blanks or have an “aha!” moment. And cutting performances by Denzel Washington — it doesn’t get much better than that. He’s very funny in this. I think Mark Wahlberg brought out a lot of his humor. It’s not a laugh-out-loud, hysterical film, but you see Denzel in a different role. He has an undercover character and then he has the DEA character. And Wahlberg’s very, very likable. At the core, the best part of the movie for me is the relationship between the two.

I’m pretty sensitive to the gunplay, considering what’s going on in contemporary American society, and I don’t want to glorify it. Still, it has its True Romance moments, but it’s not gratuitous.

CM: What is different about film editing today than when you came on Beverly Hills Cop II?

MT: Editors are much more vulnerable to forces outside the cutting room. I’ve been on both sides of the situation where editors are brought in as a fresh pair of eyes to replace another editor. Editors are more dispensable and there is a tendency to throw more of them onto something to fix it. I’m all for people looking at my work and having a different perspective, but I think it comes down to a certain lack of respect for what we do — feeling that a new editor will elevate a preview score that doesn’t reach the expectations of a studio. And I get it; there’s a lot of money invested here and obviously you want success at the box office. Ironically, the current trend in involving several editors is good for employment.

CM: Any other highlights for you?

MT: The best thing that’s happened in my career was being elected to the Board of Governors at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences [AMPAS], representing the Film Editors branch. The more I have to do with my colleagues, the more I am convinced that this is a terrific group of very honorable, very hard-working, talented people, but sometimes we’re not treated as such.

I don’t want to sound like the old, grizzled veteran who’s just complaining all the time. I’m so grateful for what I do. I just want our artists to be treated respectfully and appreciated for the time and efforts that we put into shaping the final outcome of a movie.