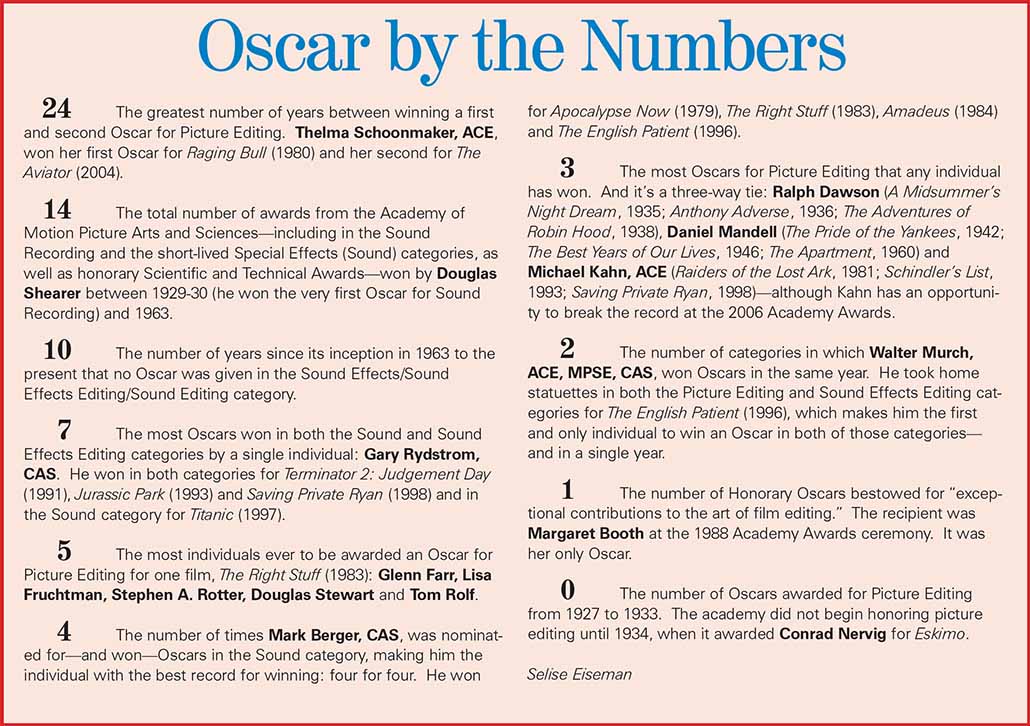

by Selise Eiseman

Many of the first individuals who won Academy Awards in the picture editing and sound categories were pioneers in their respective fields and ran most of the studio’s post-production departments from the beginning of the transition to sound feature films in 1927. Many of them had fascinating backgrounds outside of film—in diverse fields such as philosophy, romance languages, electrical engineering—that infused their artistic and scientific curiosity to work in sound recording, sound effects editing and picture editing.

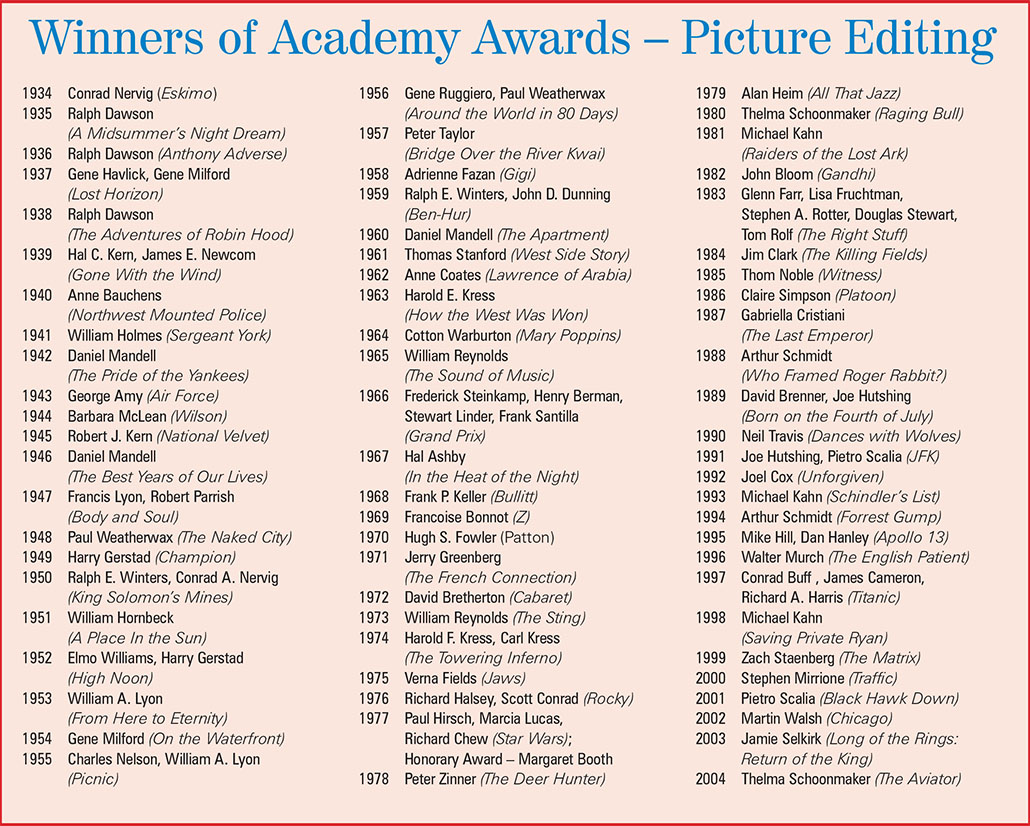

In honor of the 78th Academy Awards on March 5, Editors Guild Magazine takes a look back at the winners in the post-production categories dating back to the early days of Academy Awards in the late 1920s, and offers brief profiles of several members of the exclusive, multiple-Oscar-winning alumni group in order to highlight their multi-faceted achievements.

Douglas Shearer

was the organizer of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s sound department in 1927 and the director of its technical research until his retirement in 1968. He entered the film industry by accident when he came down from Montreal to visit his sister, Norma, who was already an important MGM star. With a background in engineering, he became interested in adding sound to her latest film, Slaves of Fashion (1925). He was hired as an assistant cameraman, but was soon inventing trick camera effects. The Jazz Singer (1927) made all the studios pay attention to sound and, as a result, he set up the department. His background led him to be involved in every scientific aspect of filmmaking, and he is credited with designing a new type of sound system for theaters and advancements in cameras, projection work, color balance and background process photography.

Shearer and the MGM sound department received the first Academy Award in 1929-30 for Sound Recording on The Big House. The all-time multiple-Academy Award-winning champ went on to win four others in 1935 (Naughty Marietta), 1936 (San Francisco), 1940 (Strike Up the Band) and 1951 (The Great Caruso). In addition, he received two Special Effects Oscars—for Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944) and Green Dolphin Street (1947). Also, he received several Scientific and Technical Awards plaques and citations in 1935, 1936, 1937 (two awards), 1941, 1959 and 1963. The 1959 award was for co-developing the Camera 65, a system of producing and exhibiting wide-film motion pictures, which continued an earlier interest in 70mm three decades before.

Film historians have said that Shearer was to MGM in sound what Cedric Gibbons was to MGM in art direction. Los Angeles Times film critic Kevin Thomas mentions in Shearer’s obituary that he was as familiar as Leo the Lion’s roar and that the films on which he worked had a “kind of subliminal guarantee that there was a continuity and permanence in the pleasurable escapism of going to the movies, especially MGM’s glossy productions.”

Conrad Nervig

began his career in 1922 at the Goldwyn Studios and worked in the industry for over 30 years. In 1934, he was the recipient of the very first Oscar awarded for Picture Editing for the MGM production Eskimo. Nervig won his second Oscar in 1950 for King Solomon’s Mines, sharing it for the film with Ralph Winters, ACE. In between these two wins, Nervig edited, among others, A Tale of Two Cities (1935), The Big Store (1941), I Married an Angel (1942) and Courage of Lassie (1942). His last editing credit was Death of a Scoun-drel, which was released in 1956.

In a letter to the editor of Cinem-editor, the magazine of the American Cinema Editors (now called CinemaEditor), in Spring 1964, responding to readers’ questions about what ever happened to him, Nervig wrote back from Ramona, California, saying that he was enjoying his retirement and missed his friends—but did not miss working since 1954.

George R. Groves

was the longtime head of Warner Bros. sound department. He began in 1923 at Bell Telephone Lab by experimenting with electrical recordings and synchronizing records to motion pictures. In 1925, he joined Warner Bros. in New York, and the following year became a recording engineer when Warners took over the Manhattan Opera House to record the score of Don Juan.

By 1927, Groves moved to Hollywood as part of the studio sound department working on The Jazz Singer. He won his first Oscar as part of the Warner Bros. sound department team under Nathan Levinson in 1942 for Yankee Doodle Dandy, and subsequently won again under his own name in 1957 for Sayonara and 1964 for My Fair Lady.

In an article written by Bernard Brown in Screen Classic (November-December 1976), Groves was recognized as one of the chief pioneers of the talking motion picture sound team that produced The Jazz Singer. Just before his retirement in 1972, he supervised the design, engineering and construction of the music recording complex at the Burbank Studios (now Warners’ studio lot).

John Paul Livadary

was a motion picture sound pioneer who began at Columbia Pictures in 1928—a year after The Jazz Singer was filmed. He won three Oscars for Sound Recording: One Night of Love (1934) as sound director of Columbia’s sound department, The Jolson Story (1946), and From Here to Eternity (1953). Livadary was also recognized by the Academy between 1937 and 1954 with four Scientific and Technical Awards for the patents he held on magnetic tape and multi-track recording systems. He was known as the technician’s technician.

Originally moving to the United States after studying medicine in Greece, he served in the Army and then attended MIT, from which he graduated with advanced degrees in electrical engineering and mathematics. Livadary went to work for Bell Lab-oratories for four years, spent six-months at Para-mount, and then began his long tenure at Columbia.

His work on One Night of Love innovated the way opera arias were recorded for motion pictures. Livadary and his assistants put the arias on “hill and dale” records, so called because the grooves are cut in different vertical depth instead of side-by-side. In the 1933 Motion Picture Almanac, Livadary stated, “Sound perspective is highly important and is a comparatively recent improvement in motion pictures… Such perspective makes the voice have just the right volume and quality for whatever distance the player may be from the camera.”

Daniel Mandell

received three Academy Awards for Picture Editing. The first was for The Pride of the Yankees (1942), the second for The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) and the third for The Apartment (1960). He actually began his career in show business as an acrobat in his family’s troupe, “The Flying Mandells,” also known as “The Mandell Brothers.” He toured the country with the Ringling Bros. Circus before switching to vaudeville and performing four shows a day. After fighting in World War I, Mandell followed the advice of a childhood friend who was working as an editor at MGM and decided to try his luck in the film industry. His first official editing credit was on The Matchmaker in 1920.

Mandell worked at various studios, including stints at Fox, Universal, Pathé, RKO, and Warner Bros., before joining Samuel Goldwyn Studios. His work at Goldwyn from 1935 to the early 1940s included Dodsworth (1936), Dead End (1937), Wuthering Heights (1939) and The Little Foxes (1941). He once commented to Howard McClay in The Los Angeles Daily News in 1951 that working with Goldwyn was “an experience. He expects the impossible, and somehow manages to accomplish it. He is never completely satisfied. He pounds away until he gets what he wants and it always seems to turn out right. He’s usually four jumps ahead of you and it’s a merry chase to catch up.”

Mandell said that his background as an acrobat benefited him as an editor because it enabled him to develop a sense of how audiences react. “Timing was the most important factor in this respect,” he told McClay, and learned to figure out what people laughed at—and didn’t. Among his later credits are Guys and Dolls (1952), Porgy and Bess (1959) and five additional films for writer/director Billy Wilder (besides the aforementioned The Apartment): Witness for the Prosecution (1957), One, Two, Three (1961), Irma La Douce (1963), Kiss Me, Stupid (1964) and The Fortune Cookie (1966).

Frederic C. Hynes

entered the industry in 1928 as a sound engineer at Pathà Studios and in 1930 joined RKO Pictures, where he was involved in the installation, maintenance and operation of sound recording equipment. He won five Oscars for his work on Oklahoma (1955), South Pacific (1958), The Alamo (1960), West Side Story (1961), and The Sound of Music (1965).

Hynes joined the Todd A-O sound department and spent 30 years there, becoming the executive vice president and then General Manager. He helped develop the Todd A-O system, a six-track, wide-screen sound system, which was first used in Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Hynes was also the 1989 recipient of the academy’s Gordon E. Sawyer Award, which recognizes “long-term accomplishments by an individual who has made outstanding contributions toward the advancement of the sciences and technology of the movies.”

Ralph E. Winters, ACE,

in his nearly 70-year career, worked on almost 80 films. His father was a tailor at MGM and helped him get a job at the studio right after high school. He went to work in the editing department, first helping to cut shorts and later, after the transition to sound, features. His first assignment as an editor was Mr. and Mrs. North (1942) starring Gracie Allen. In the 1940s and 1950s, he began editing musicals and epics and segued to working with Blake Edwards on many of his films, including The Pink Panther series, and also with Norman Jewison, Delbert Mann, John Cassavetes and Richard Fleischer.

In 1968, Winters edited The Thomas Crown Affair, which explored new film editing techniques, and also cut the 1976 version of King Kong. He won two Oscars—one for King Solomon’s Mines (1950), shared with Conrad Nervig, and the other for Ben-Hur (1959), shared with John D. Dunning—in addition to being nominated six times. He served on its board of governors. Winters was also President of the Editors Guild (1965-1966).

He told The London Times that he spent three months editing the famous chariot race in Ben-Hur, going back to it again and again in his search for perfection. His autobiography, Some Cutting Remarks, was completed by the oral history department of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Winters told fellow editor Frank Urioste, ACE, who first met him at MGM in the late 1950s and worked with him on several films, “You can teach the fundamentals [of editing], but the actual art of doing it is something you can’t teach.” Winters’ last editing credit was on Cutthroat Island in 1995. He died in February 2004.

Photo courtesy of and Copyright AMPAS

William Reynolds, ACE,

edited or co-edited nearly 80 films as well in a career that spanned 60 years. They ranged from science fiction classics like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) to musicals such as Carousel (1956) and Hello Dolly (1969) to epics the likes of The Godfather (1972) and Heaven’s Gate (1980). Born in Elmira, New York, Reynolds graduated from Princeton University in 1933 and moved to Los Angeles. His first job was as a prop handler at 20th Century-Fox and, under the tutelage of Darryl Zanuck, he moved into the editing room in 1935. He made rapid progress in developing his craft, and his first film as an editor was two years later on 52nd Street.

During World War II, Reynolds was assigned to the Army’s filmmaking unit, where he directed, edited and produced training films. By 1947 he was back in Hollywood. He won Academy Awards for his editing on The Sound of Music (1965) and The Sting (1973), and was nominated for five other Oscars. Reynolds worked with a multitude of directors, including John Cromwell, Lloyd Bacon, Lewis Milestone, Henry Koster, Robert Wise, Henry King, Joshua Logan, Elia Kazan, Francis Coppola, Arthur Hiller and George Roy Hill.

Wise, for whom Reynolds cut five films, commented, “I valued Bill’s judgment more than I did anybody’s.” Hiller, who worked with him on four films, said that Reynolds “edited by feel, not by rote. Every film he touched became a better film.” When Reynolds worked with Michael Cimino on Heaven’s Gate, he claimed that nothing in his long career had prepared him for the experience of editing 1.5 million feet of film on a KEM editing machine!

Harold “Bill” Varney, CAS

worked 30 years as a re-recording mixer and joined Universal Pictures as vice president of sound operations, where he was responsible for the complete remodeling and upgrading of the studio’s sound facilities. He also spent a 14-year stint at Goldwyn Studios as supervising re-recording mixer. Varney began his career in radio and television in the early 1950s. His first motion picture was a government-funded project at MIT featuring folk singer Joan Baez, whose father was a professor of physics there. This film caught the eye of some filmmakers, and before long, he moved to the West Coast. He won two Academy Awards––for his work on The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Varney is a past president of the Cinema Audio Society and a member of the executive committee of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Along with Walter Murch, ACE, MPSE, CAS, he used a 58-page memo from Orson Welles to reconstruct the sound for the DVD re-release of the Director’s Edition of Touch of Evil in 1998.

Sound Oscars for West Side Story (1961). Actors Joanne Woodward and Anthony Fransciosa were presenters at the 34th Academy Awards. Photo courtesy of and Copyright AMPAS

Steve Maslow and Gregg Landaker

as Re-Recording Mixers shared Varney’s Oscar for work on The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Raiders of The Lost Ark (1981). The pair also won for Speed (1994). In addition, the duo received Oscar nominations for Dune (1984), Waterworld (1995) and Twister (1996). They began as a mixing team at Warner Hollywood Studios in the late 1970s with their first collaboration, More American Graffiti (1979). Since the mid-1990s they’ve worked in the sound department at Universal Pictures and had a hand in designing a state-of-the-art automated mixing console specifically tailored to accommodate them. Varney once told Variety, “Gregg and Steve are the best sound-mixing team in the business.”

Pietro Scalia, ACE,

was born in Italy and earned his MFA at UCLA Film School. He cut commercials and began his career writing, directing and editing several independent projects, documentaries and experimental films. He worked at Cannon Films as first assistant editor on Andrei Konchalovsky’s Shy People, and met Oliver Stone there, which led to a job as an assistant editor on Wall Street and Talk Radio. This began his long collaboration with the director; he worked as an associate editor on Born on the Fourth of July and as an additional editor on The Doors.

Along with Joe Hutshing, ACE, Scalia won the Academy Award for Editing for Stone’s JFK (1991). He brought home his second Oscar for Black Hawk Down (2001). He also collaborated as a music producer with composer Hans Zimmer and director Ridley Scott on the soundtracks for Gladiator, Hannibal and Black Hawk Down. Most recently, he edited Memoirs of a Geisha.

Academy Awards. Actor Jason Robards was the presenter. Courtesy of and Copyright AMPAS

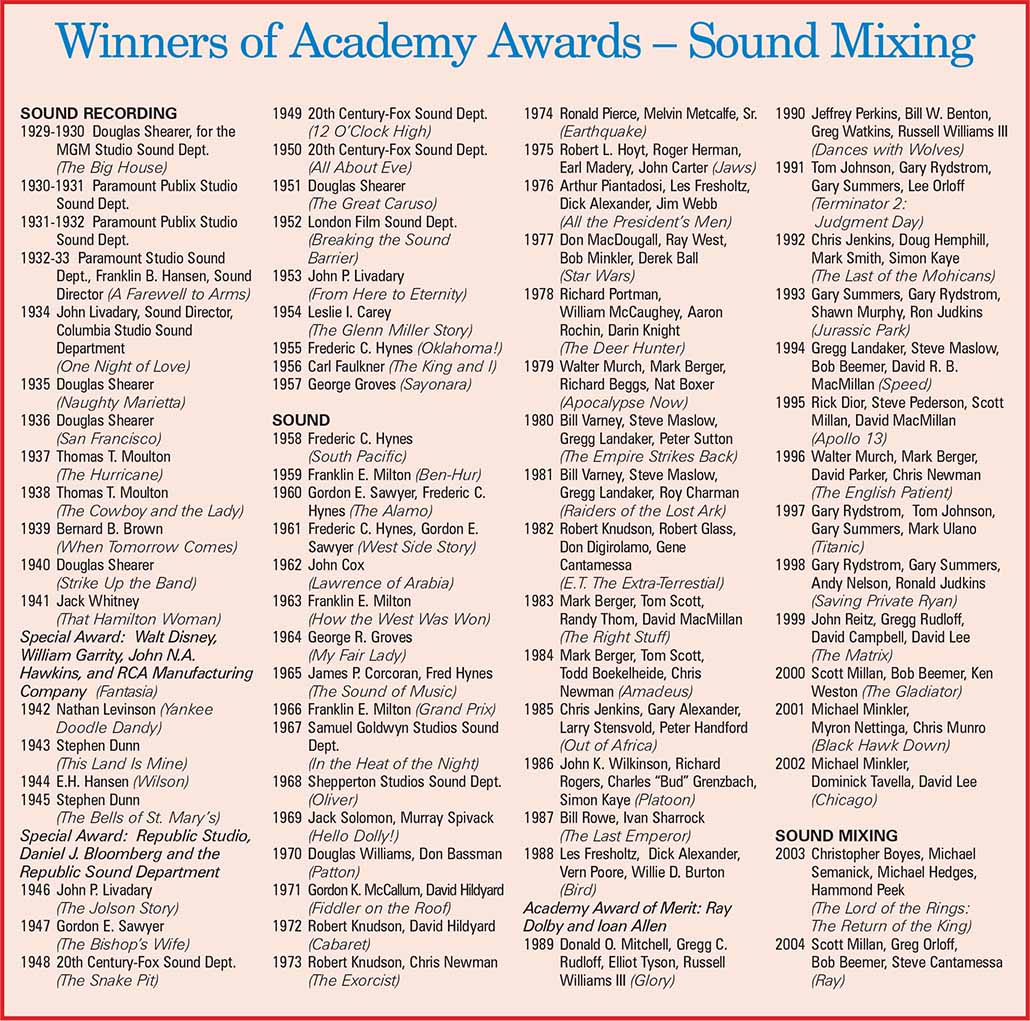

Others in the sound area who have won two or more Oscars include Bob Beemer, CAS; Mark Berger, CAS; Christopher Boyes; Ben Burtt, Jr.; Charles Campbell; Steven Dunn; Les Fresholtz; Richard Hymns; Robert Knudson, CAS; Louis Mesenkopf; Franklin E. Milton; Michael Minkler; Thomas Moulton; Walter Murch, MPSE, ACE, CAS; Gregg Rudloff; Gary Rydstrom, CAS; Gordon E. Sawyer; Tom Scott; Gary Summers; and Jack Whitney.

In the picture editing category, other multiple-Oscar winners include Ralph Dawson, Harry Gerstad, Joe Hutshing, ACE; Michael Kahn, ACE; William Lyon, Arthur Schmidt, Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE; and Paul Weatherwax.

The lives of all of these winners were/are rich with opportunities; most were/are self-made men and women who received the recognition of their peers in their various disciplines. Some of them work on both sides of the craft and received recognition for both, like Murch (picture editing and sound editing and mixing) and Rydstrom (sound editing and sound mixing). Others solely became the top expert in their field, whether they began working solo or as a team and/or later managed others in a supervisory or administrative capacity. All of them loved/love their craft and proved that hard work was necessary to rise to the top of their profession.

Most of the winners had the chance to work over and over again with some of the same people on their creative team and this collaboration undoubtedly made the process and their creative juices flow. Consequently, it allowed them to do their best work and the Oscar statuettes multiplied.

Oscar’s Women

Although nowhere near as well represented as their male counterparts in the Academy Awards pantheon, women in post-production nonetheless gained recognition for their craft and brought home some Oscar gold.

The first woman to win an Academy Award for picture editing was Anne Bauchens for Northwest Mounted Police in 1940. Four years later, Barbara McLean won for Wilson (1944). She is the most nominated female editor, receiving seven nods for her work from 1935 through 1950, but only that one win (see related story on pioneering women editors, page 32).

Other female Oscar winners for picture editing include Adrienne Fazan (Gigi, 1958), Anne V. Coates, ACE (Lawrence of Arabia, 1962), Francoise Bonnot (Z, 1969), Verna Fields (Jaws, 1975), Marcia Lucas (Star Wars, 1977), Lisa Fruchtman, among others (The Right Stuff, 1983), Claire Simpson (Platoon, 1986) and Gabriella Cristiani (The Last Emperor, 1987).

Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE, is the only woman to receive two Oscars. The first was for Raging Bull (1980) and the second for The Aviator (2004)

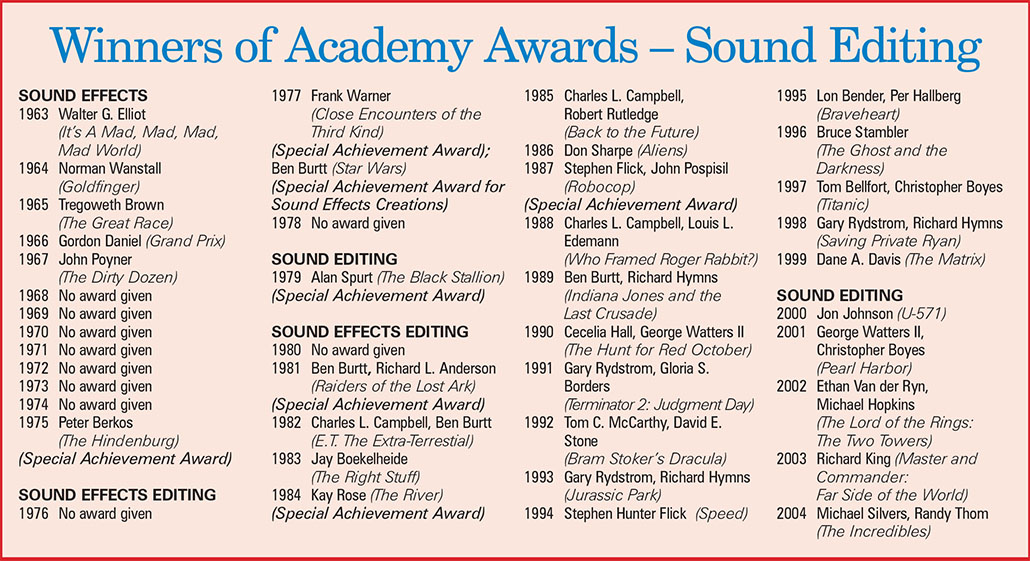

Some Sound (if not so Clear) Facts About Oscar

The first Academy Awards to honor sound was 1929-1930, the third annual ceremony (after 1927-1928 and 1928-1929). The Oscar was awarded for Best Sound Recording and was presented until 1957. (Curiously, the academy did not award picture editing—which pre-dated sound in motion pictures by more than a decade—until 1934.)

Beginning in 1958, the award category was changed to Best Sound. From 1929 to 1968, the Sound Recording/Sound Oscars were awarded to the studio sound departments and/or the individuals who were named as sound directors. Beginning in 1969, the award went to the individuals responsible for the sound mixing work on the honored film.

In 2003, the award category’s name was changed to Sound Mixing.A separate Sound Effects Award was established in 1963. Confusingly, the category has had three names since it was first given in that year. It became Sound Effects Editing in 1976 and kept that name for 22 of the next 23 years. For the single year of 1979 it was called Sound Editing and then took that name again in 2000 and has remained so ever since.

Since 2004, Academy Awards rules guarantee three nominations in the Sound Editing category. According to the rules, “Seven productions will be selected by preferential ballot by all eligible members of the sound branch. Those seven films will be screened for the members of the Sound Editing Awards Committee, which will select the three nominees (the so-called ‘bake-off’). Final voting will be by all eligible members of the academy.”

Previous academy rules permitted three annual options for the Sound Effects/Sound Effects Editing/Sound Editing Award, according to the academy’s website: “The voting by the Board of Governors of a Special Achievement Award for Sound Editing; placement on the final ballot of two or three nominated achievements to be voted upon by all voting members of the Academy; or no award in a given year.”

Indeed, a Special Achievement Award was given in Sound Effects/Sound Effects Editing/Sound Editing in 1975, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1984 and 1987.

To complicate matters, an award for Special Effects (Sound) was presented from 1938 to 1945, and in 1948 as Special Effects (Audible)—but let’s not go there…