by Sharon Benoit

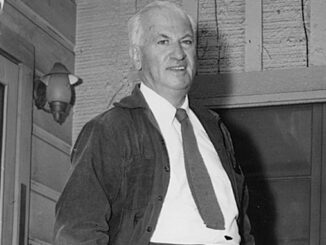

Most people look forward to the day they can call it quits and retire. That’s just not been the case for 95-year-old editor James (Jim) E. Blakeley, ACE. This legendary and highly respected film editor looks forward to driving his classic 1965 Mustang about 10 minutes to the office every work day; and he thoroughly enjoys editing film with 79-year-old Rudolpho (Rudy) Freeman until 6:00, 7:00 or 8:00 p.m. each night (depending on the job). This amazing scenario has been occurring for the past 53 years on the 20th Century Fox lot in West LA.

In fact, Blakeley’s business card reads: “Post-Production Coordinator, TV Syndi-cation and Worldwide Non-Theatrical.” Basically, this means that after a film is shown in theatres, Blakeley and Freeman re-edit the film for airline and syndicated television use.

“Airlines don’t want to see a lot of nudity and sex, overblown violence, profanity, etc., so we cut it out and make it work,” explains Blakeley. “We usually have to cut movies from 100 or 99 minutes down to 88 minutes for the TV networks, too.”

Freeman adds, “If we are lucky enough to receive alternate versions of the action and ADR, it makes the editing less difficult. Every airline is different. Of course, TV is a little more lenient than the airlines. Whatever is deleted is done without harming or destroying the storyline, so the viewer never misses a thing.”

Working out of Room 151 in Building 26 at Fox, Blakely reminisces about his work with many great editors of yesteryear, such as Hugh Fowler, Dorothy Spencer, Barbara McLean and Robert Golden, ACE at MGM, Columbia, Warner Bros. and Universal over the years.

An incredibly tireless worker, he rarely thinks about overcoming great challenges. “Every day there’s a different challenge because I work on a different picture,” says Blakeley. “Rudy and I have been a team for about 30 years now; he’s an excellent editor.”

Freeman, a native of Los Angeles, interjects, “Technically speaking, we have come a long way in the motion picture industry, but as far as stories and acting go, we’ve taken a step backwards. Most of the stuff we see today…I really don’t know why some of the films are made. Today, it’s a business [as opposed to entertainment].”

A former member of the Editors Guild Board of Directors, Blakeley divulged that they usually re-edit between three and four movies a month. “When it rains, it pours,” he added. “That saying seems to come true in our work.”

Blakeley has been married for the past 63 years to Mary Carlisle, a former film star, who started out in 1930 on contract to MGM in the film Grand Hotel. Early on, Carlisle and her future husband had a lot in common; Blakeley started out as an actor, which was in his heritage.

Born in London, England in 1910, he is the son of the famous British actor James Blakeley. When his father was killed during World War I, the family moved to the US and settled in New York, where his mother eventually re-married. Blakeley received private schooling and enjoyed a privileged life during the Great Gatsby era.

“Whatever is deleted is done without harming or destroying the storyline, so the viewer never misses a thing.” – Rudy Freeman

His life took a dramatic spin when Harry Cohn, then president of Columbia Pictures, noticed him dancing with actress Barbara Hutton at New York’s Central Park Casino in 1933. Cohn offered Blakeley a screen test that resulted in a contract with Columbia.

He was placed in such films as The Captain Hates the Sea (1934), Paris in the Spring (1935), The Gay Desperado (1936) and The Shadow Strikes (1937), and acted alongside great stars like Lucille Ball, Bing Crosby, Ida Lupino and Fred MacMurray. During the early 1930s in Hollywood, he dated a few actresses, including Olivia de Havilland. Early in their marriage, Blakeley and Carlisle were frequent guests of William Randolph Hearst at his palatial estate in San Simeon, California.

Then World War II broke out. Blakeley enlisted in the US Army Air Corps (later the US Air Force) and became the director and general manager of the Embry Riddle School of Aviation in Miami, Florida, which trained Army pilots and ground crews.

He was later sent to São Paulo, Brazil, to build and manage a similar facility, Escola Technica de Aviacão.

After the war, Blakeley helped his friend, Elizabeth Arden, get her cosmetic company off the ground and served briefly as general manager for Elizabeth Arden Cosmetics. During that time, he was sent to South America where he built factories in Rio de Janeiro, as well as in Mexico City and Havana. Following his time with Elizabeth Arden, he returned to Hollywood in 1950.

It was through Carlisle’s uncle, Grant Whytlock––a well-known film editor who worked on the 1921 classic The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse––that Blakeley was initiated into the craft of film editing in 1952. His first job as an editor was on the Lassie TV series, which began its long run in 1954.

Freeman also started out as an actor. “I was a bit player,” he confesses. “I went through all of the dramatic schools in Hollywood, but never made it into stardom. I also started working in the business as a mail boy and messenger in 1946. Then I broke into publicity, which was a lot of fun. In 1955, I made a transition into film editing. I’ve worked for 20th Century Fox for about 60 years. Jim and I started working together in 1952. It’s been a great experience.”

“Every day there’s a different challenge because I work on a different picture,” – James Blakeley

Today, Blakeley is considered to be one of the deans of film editors. His instant recall of scenes in films on which he worked as long as 50 years ago is remarkable. They include such classics as Les Misérables (1952), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), Monkey on My Back (1957) and Patton (1970), as well as such TV series as Rawhide (1959-66), Peyton Place (1964-69), Batman (1966-68) and The Green Hornet (1966-67).

“I remember every scene I’ve ever edited,” he states with a very distinguished recognition of when and where it occurred. But he also believes every good editor should be able to easily do that. Blakeley is also very proud of his role as a four-year president of the prestigious American Cinema Editors in the early 1980s.

In these days of digital technology, Blakeley and Freeman still use an old-fashioned Moviola on occasion in their editing suite. It’s still their favorite working tool. But, according to Freeman, “Everything today is computerized.”

Freeman continues, “We look at the finished product on a big screen, make notes of what we need to eliminate, and then delete what needs to come out for the airlines and TV networks. We work from separate stem masters on ProTools, along with other elements. Most often we are not given ADR elements and alternative coverage so, like most editors, we use our own expertise to eliminate what we have to so the scene plays.”

Freeman can’t resist making another comment about contemporary cinema. “To be an actor today, all you have to do is jump over a car, scream, whisper or jump into bed,” he claims. “Everything else is a special effect.”

Mention the word retirement to Blakeley or Freeman and they just smirk: “Why should we? We’re having way too much fun…”