If you could record every moment of your life, would you? In the new feature film The Final Cut, parents can buy their child immortality with a Zoë implant, which is attached to the brain and programmed to activate at birth. It then begins recording that person’s life through his or her own eyes until death. After that, the implant is removed and given to a “cutter,” who edits a lifetime of footage into a “Rememory”––a movie of that life to be replayed for family and friends.

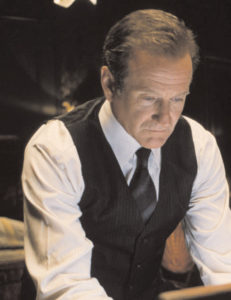

But The Final Cut is really about the editor. Robin Williams plays Alan Hakman, the best “cutter” in the business, who specializes in working with the sometimes ugly and disturbing footage that is captured on these implants that never turn off and never look away.

The feature film debut for director Omar Naïm from his original screenplay, The Final Cut was co-edited by Dede Allen, ACE and Robert Brakey. The three filmmakers recently convened to discuss the concepts and the process behind the making of this film, as well as its relationship to the craft of editing.

Robert Brakey: Omar, how did you get the idea to write a script about a film editor? No one has ever really made a film about editing and editors.

Omar Naïm: I was finishing my thesis film, a documentary, and I spent seven months editing on the Avid. I realized how creative editing can be and that if you understand the editing process, you really understand how a movie is put together. So I thought it would be interesting if someone’s life could be recorded and an editor had to interpret this life and make sense of it for posterity––and what sort of burden and responsibility would that editor have.

Dede Allen: What I love most about the idea of this movie is that it reminds me of the way the mind works. We’re all visual, we all have these pictures in our minds…these memories that we flash through all the time. That’s why a motion picture can speak so strongly to something emotional in us.

“I love scenes that are fast and full of action. People always assume those scenes are the most complicated to work with.” – Dede Allen

ON: Movies resemble the way we remember our lives, much more than they resemble the actual experience of our lives. There’s no cutting in real life, but our memories are edited and altered.

RB: And in the “Rememories” in the film, the reality for the audience is the finished product. Just like when we edit, we’re creating a reality by making choices and directing the audience to look in a certain place or react a certain way.

ON: But memory can be as manipulative as any filmmaker. Our brains make selections and change things all the time.

RB: And when Alan is searching for the truth in his own life, he has to go back. For him, the truth is in his dailies. It’s interesting too that what makes Alan the best editor also makes him completely dysfunctional as a human being.

ON: He is so intimately knowledgeable about other people’s lives, and so oblivious about his own. For me, the challenge was to take these ideas and tie them to a human experience that everyone could relate to. And when it became time to choose an editor, the very first person I wanted to cut this film was Dede. I wanted to work with her because I knew that the film needed to function foremost as a human drama. The world and the technology is made up, so the characters had to be believable, especially Alan. And in the wide variety of films that Dede had worked on, the common thread is the humanity of the characters. It was a far-fetched idea, but she said yes.

“I gained confidence in my instincts and my taste, so I was more comfortable taking a chance without worrying about it not working.” – Robert Brakey

DA: Well, it was a fascinating idea. I really liked the script and I especially liked the character of Alan.

ON: Rob, how did you get the chance to work with Dede?

RB: Dede called me and said, “I’m doing this interesting picture and would you like to be my assistant on it.” I told her I was very grateful she had called but I had cut a film the year before and wanted to keep cutting. She said, “Okay, that’s great,” and that was that. And I thought, “Great, now I’ll never work with Dede Allen. I blew it.” But she called back and asked if I would co-edit the film with her, which is like winning the lottery.

DA: Well, I wanted to bring you on because I felt you were ready for it, as a co-editor. I was impressed by what everybody said about you––editors I respect who had worked with you––so I thought it was very logical and natural.

RB: When we started, I didn’t know how it would work. I thought Dede would pick the scenes she wanted and go in a room, and I would get the rest and go in another room, but we found a method of working together on every scene which was an incredible experience and education for me. I’ll never forget that

.

DA: We were so careful watching dailies together every day––that’s when we made all of our notes. Then we cut every scene together. It was completely co-edited in that sense.

RB: And that kind of collaboration never happens. Usually you’re alone in a room.

“The challenge was to take these ideas and tie them to a human experience that everyone could relate to.” – Omar Naïm

DA: That’s because we’re editing on Avids; that wasn’t the case when we cut on film. There was always an assistant right there, handing you the trim, and over time they got to think so much like you, they knew which trim to hand you next. And that’s gone; that’s been lost.

RB: I was always obsessed about cutting on the exact frame and matching and other details, and Dede taught me to open my mind and shift my focus more to the story and the characters and the flow as a whole.

DA: To be a little looser with your perfectionism. Be freer and bolder. It’s true of all people starting out editing. When you start, the technique is what you’re really concentrating on; and later, when the technique’s under your belt, you can free yourself and make bolder choices.

RB: I gained confidence in my instincts and my taste, so I was more comfortable taking a chance without worrying about it not working. That’s how you sometimes find the best choice.

DA: That’s one of the most important things to learn. On film, it was so much easier to train apprentices and assistants, because coming up through the cutting room, it was always a group thing, and that’s how you learned. I think the ability to do that is more difficult with the new method of working.

ON: Were you surprised by the footage, the way it looked or the tone of it? What was it like seeing the film appear, piece by piece?

DA: The only thing that worried me was when you did certain complex masters that took a long time to do, you might not have the time to cover. For example, I knew we wouldn’t be able to stay on that shot that cranes up and tilts down to establish the guillotine [Alan’s cutting machine in the film]. I remember one shot that was so wonderful––from behind the guillotine––and you move slowly up between the monitors. I love that shot; it’s such a great angle and I was so happy you had done that. It gets a little boring when it’s all over the shoulder.

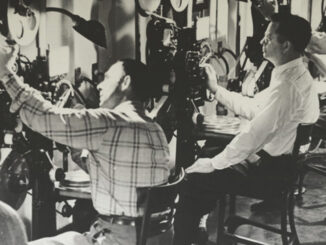

Photo by Rob McEwan; courtesy of Lions Gate Films

RB: Omar, when we first met you asked what I thought the guillotine looked like and I said, “futuristic and sleek, aluminum, or maybe clear like that machine in Minority Report.” And you said, “No, it’s all wood. Dark wood.” That’s when I knew this movie was going to look completely different from what I had pictured. How did you feel when you saw the first cut?

ON: It wasn’t a shock. I went scene by scene, thinking, “Oh, this is interesting… How surprising… How neat… How cool…” But then there were certain scenes that I’d shot only one way because I wanted them cut that way, like the split screens.

RB: We didn’t even put that scene in the first cut, we saved it for later when you were in the room.

ON: And I remember Dede called the chase scene “dessert.”

DA: I love scenes that are fast and full of action. People always assume those scenes are the most complicated to work with.

RB: Cutting any kind of action is fun, especially a chase.

DA: I would always cut it silent and then track it afterward. We did some of that on this film.

RB: Sometimes––and we also did the opposite––we would turn off the picture and cut just the dialogue until the cadence was right, then fix the picture cuts to work. We used both ways. But the chase scene, we cut that silent for a long while.

DA: Definitely; there’s no reason to hear it, it’s just noise. You know there’s a few lines and you can read the lips on those––and you can feel the overlaps.

ON: That chase was my first day of shooting; it was intense.

RB: That’s like putting the needle somewhere on a record and hitting the note you want to hear.