by Rob Callahan

When the interests of employers and organized labor clash, the legal landscape has rarely offered a level playing field for American workers. The legal battles we face tend to be uphill, and the slope only seems to grow steeper. When we fight and win, we do so not because we have statutes or courts on our side, but because we have the extralegal strength that comes from steadfast solidarity among co-workers.

Since 1935, the National Labor Relations Act has putatively protected and promoted employees’ right to organize. The legal safeguards it affords workers, though, too often prove toothless.

Proposed legal reforms that would have made it easier for workers to unionize free from employer intimidation faltered and died early in President Obama’s first term. In recent years, anti-labor legislative initiatives in several states, including an explosion in so-called “right to work” laws, have further curtailed unions’ clout in collective bargaining. And the Supreme Court recently announced that it will hear a case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, that threatens to make “right to work” (the outlawing of contractual clauses requiring all represented employees to pay their fair share of the expenses of collective bargaining) the law of the land nationwide for public sector employees. The law is seldom on our side, and the scales steadily tip further still in management’s direction.

A few recent decisions and rule changes by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) present modest but notable exceptions to this general trend of a legal landscape littered with seemingly ever more obstacles to collective bargaining rights. Under its current leadership, the NLRB — the federal agency charged with implementing labor law — has taken more seriously the law’s promotion of workers’ right to organize to improve their jobs. The NLRB has recognized that employees can use e-mail and social media to discuss their working conditions and push for improvements. The Board has indicated that corporations like McDonald’s will no longer be able to hide behind their franchisees when corporate policy determines workers’ terms of employment. The Board has held that smaller groups of similarly situated employees can opt to unionize, without all the employees of a large employer agreeing to do so.

Under pressure from management, democracy deferred effectively amounts to democracy denied.

One of the more significant shifts in the legal terrain for employees interested in organizing has been the NLRB’s revision of its procedures for holding union representation elections. When a group of employees at a non-union workplace seek union representation, they can petition the NLRB to hold a vote; after employees vote to unionize, the Board instructs their employers to negotiate with their elected representatives. This process has long been broken because it has given employers plenty of opportunity to bog employees’ petitions down in legal challenges in order to delay the time to an election.

Employers almost invariably use these delays to campaign against unionization, often using tactics that are intimidating or coercive. When employees are subjected to daily admonishment from their bosses, often including implicit threats about the consequences of a Union Yes vote, workers’ confidence in their ability to win improvements in the workplace can flag. Anti-union campaigns can prove highly effective because employers use the period between petition and election to bombard employees with doubts about the possible repercussions of challenging the status quo. Under pressure from management, democracy deferred effectively amounts to democracy denied.

The NLRB’s update to its elections process took effect in April of this year. The changes are modest, and include common-sense measures to modernize elections, such as provisions that employers provide unions with the telephone numbers and e-mail addresses — not just mailing addresses — of employees eligible to vote. The most meaningful change is that the new procedures significantly limit the employer’s ability to gum up the process in unnecessary delays. Under the new rules, the median time between employees filing a petition and the Board conducting an election is 24 days. Under the old rules, if an employer wanted to challenge the petition, a wait of about two months was the norm. The adjustment to election policy isn’t game-changing, but it does give bosses a little less opportunity to run down the clock.

What do these changes mean for our union? When organizing non-union productions, the Editors Guild and the IATSE have rarely had recourse to NLRB elections, simply because shows’ production and post schedules usually don’t offer enough time for all the Board’s bureaucratic processes to play out. That probably won’t change under the new rules. The rules may, however, make the NLRB elections process marginally more viable for organizing campaigns at post-production facilities or for company-wide (rather than show-specific) campaigns. It will still take employees demonstrating tremendous courage and commitment to vote for change in the face of pressure from bosses. But any measure that reduces management’s obstructionism will help a little.

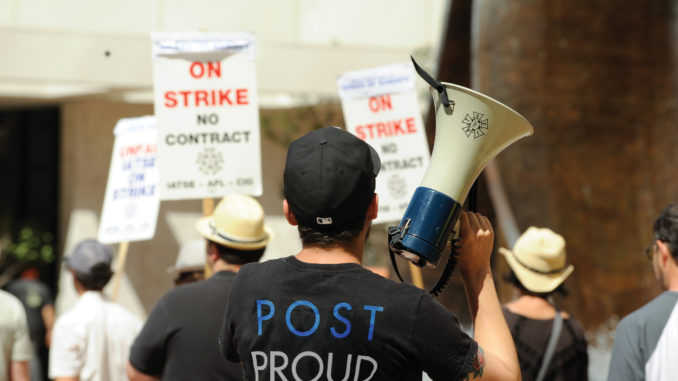

If you work in post-production in a non-union workplace, and you think your co-workers would be interested in voting for union representation, talk to a Guild organizer. You can contact an organizer through www.postproud.org, the website for the Guild’s Organizing Department, or by mailing organize@editorsguild.com.