by Ray Zone

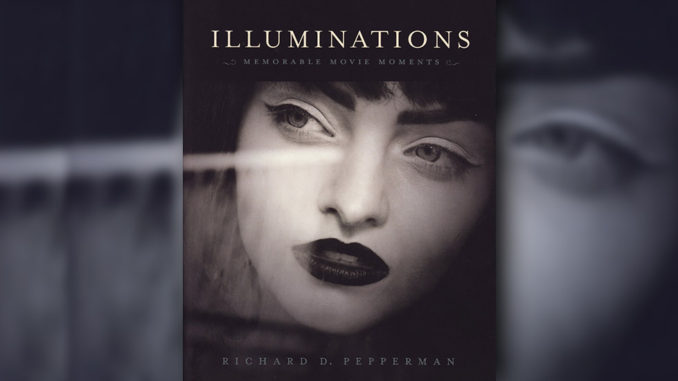

A 40-year veteran of the motion picture industry as an editor and post-production supervisor, Richard Pepperman brings a wealth of experience to his teaching and the authoring of his books on cinema. His three previous books — The Eye is Quicker, Setting Up Your Scenes and Film School — are incisive analyses, essential reading for editors and articulate valentines to the movies. With his latest, Pepperman has written his most personal book yet and, once again, it is a work that only the most accomplished editor could produce.

To research the writing of Illuminations, Pepperman assembled his library of tapes and DVDs, film guidebooks with more than 3,000 film entries and The Complete New Yorker DVD set. He also purchased The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made as well as Phillip Lopate’s American Movie Critics: An Anthology From the Silents Until Now, published by the Library of America. “Before, after, and in between this research, mostly beholden to my brain‘s seemingly unsystematic incentives,” writes Pepperman, “my thoughts, both random and ordered, set off far-fetched glints, mingling movies in abundance as well as, unexpectedly, movie houses, neighborhoods, family and friends, all scattered athwart time, spinning out windfall memories I’d likely have guessed were nowhere to be found.”

In his Introduction, Pepperman recounts seeing a movie for the first time in 1948 as a six-year-old at the Loews Apollo Theatre in New York City, taken there by his uncle Yankel. It was a time, he notes, “before motion picture ratings were requisite or age restrictions were applied.” The film was Sorry, Wrong Number, a 1948 thriller starring Burt Lancaster and Barbara Stanwyck. Based upon a classic 22-minute radio play, the film made extensive use of cross-cutting to pad out the story to feature length and, Pepperman observes, “These problems may be why the unsophisticated six-year-old me failed to follow the goings-on, and why bafflement barred my brain from a better chronicling.” He also adds that at his current age, he has “far less trouble following an entire story, but I am often distressed that unrestrained subplots and overcutting do serious harm to so many movies.”

Upon acquiring a VHS tape of the film in 1994 and revisiting it, Pepperman found the moment from it that he remembered. “My memory of the movie had preserved this single scene,” he writes. “The exactness astounded me, a result, I’m sure, of the intensely disturbing moment [in the film] — my six-year-old senses must have been on full alert.” Pepperman annotates his description of the scene with the precise time code (1:27:09-1:28:09) and three frame grabs from the film. For the author, this cinematic moment would prove to be “memorable and undying.”

Cinema is a form of public dreaming that bestows lasting images we can carry around within us for a lifetime.

Accordingly, it is Pepperman’s 1948 introduction to the movies in New York that “issues this book’s arrangement.” Each movie moment selection includes time code, stills and excerpts from contemporaneous reviews, and he acknowledges that so much of his “pleasurable research was made possible by the extraordinary writing of film reviewers and commentators.” Pepperman attempts to arbitrate, challenge, justify and preserve their original observations with “fresh considerations” of his own and others. The selections are organized by the year of a movie’s release under categories such as Inspired, Heroic, Disturbing, Spectacle, Sensual, Provocative, Uproarious, Folly, Epoch and Last Word. These categories represent his attempt to explain cinema’s influence upon him, what he “grasped, grappled with and cherished from the movies.”

To set a nostalgic and loving tone for the work, Pepperman begins with what he calls an “Overture,” which is a “call to the movies.” In this brief section, he has addressed movie moments from two films that are among the greatest love letters to cinema and the moviegoing experience ever made: The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), directed by Victor Erice, and Cinema Paradiso (1988). Interestingly, these movie moments, like most of them in the rest of the book, time out at around a minute, information of particular interest to editors.

Within the first section titled “Inspired,” Pepperman discusses a movie moment from The 400 Blows (1959), directed by François Truffaut, which had great personal meaning for him. The scene is given detailed description wherein the young protagonist Antoine takes a ride on a centrifuge known as the “Rotor” at an amusement park. “With increasing effort and laughter,” Pepperman writes, “Antoine, pinned to the whirling wall, feet off the floor, rotates upside down. Then, in an inspiring gem of a shot, the spectators, also spinning more and more speedily — in a cut of Antoine’s point of view — are now upside down. The moment will forever draw out giggles and a tummy squirm that might only be expected in real-world Rotor riders.” Pepperman adds that “The scene exemplifies the sensate command of cinema: a cadenced whirl of a dream dance.” He states that it was this film that inspired an eagerness in him to become a filmmaker and “a commitment to valued work.”

Watching movies is, ultimately, a personal matter. Cinema is a form of public dreaming that bestows lasting images we can carry around within us for a lifetime. The cadenced whirl of this dream has been elegantly explored in these pages by an experienced navigator.