by Edward Landler

From its very beginnings in the late 1920s, the Academy Awards has spawned spectator speculation on potential nominees and winners. When it was all over, and every winner-announcing envelope (please) was opened — no matter what the category — some industry-watchers approved of the choices, while others objected that sentimental favorites, over-hyped entries or downright fixes won over the really outstanding pieces of work. Arguments invariably ensued.

But over the years, the knowledge of what pictures have actually endured the test of time adds support to judgments about what pictures, or their makers, may have been robbed of rightful recognition for their achievements. This is certainly true for the category of Film Editing as well as the ever-changing sound categories: Sound Recording, Sound, Sound Mixing; and Sound Effects, Sound Effects Editing and Sound Editing.

The sound categories are the source of some confusion as their names have mutated multiple times in Oscar history. Presently, they are labeled Sound Mixing and Sound Editing. But at least Sound Recording was recognized as a category by 1929, within two years of the introduction of synchronized sound films and the Oscars themselves. Surprisingly, awards for picture editing — a craft absolutely crucial to making movies — were omitted by the Academy until 1934, when the first Oscar for Film Editing was presented.

To provide some balance to the history of perceived neglect and omissions committed by the award-selection process, CineMontage offers a sampling of motion pictures and the achievements of their post-production practitioners that qualify them for “Oscars That Should Have Been.” The singular achievements of these films represent the introduction of major innovations in the arts of editing and sound. Their qualities set these films, editors and sound personnel apart as pioneers influencing the evolution of their crafts — pioneers who should have been appropriately recognized by the Academy.

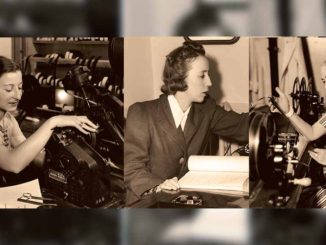

There is good cause to question the Oscar nominations from the very first year the Academy recognized Film Editing as a category. While winning the 1934 award for Art Direction, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Merry Widow, based on the Franz Lehar operetta, was not nominated for either Film Editing or Sound Recording. The Best Editing winner that year, Eskimo (Conrad Nervig), could be commended for its stark simplicity, and the operatic pieces of the Sound Recording winner, One Night of Love (John Livadary, sound director, Columbia Studio Sound Department), were neatly reproduced. But, in The Merry Widow, Frances Marsh’s editing and MGM’s sound recording under the direction of Douglas Shearer established standards for the integration of visuals and audio for decades of musicals to come.

From the very first shot of a magnifying glass searching for a tiny Balkan country on a map with an iris out on Maurice Chevalier leading a military parade through the cow-filled streets of Marshovia, the editing maintains the pace to match the film’s wit. The sure progression of dissolves and cuts marking the metamorphosis to merriment of Jeanette MacDonald’s widow as she sings, writes in her diary and changes her décor and wardrobe — and her pet dog — from black to white turns the movie into a visual symphony of ebony and ivory. “The Merry Widow Waltz” at the Marshovian Embassy in Paris culminates the symphony, intricately inter-cutting MacDonald dancing with Chevalier as empty rooms and halls fill with waltzing partners and the evolution of the central romance is matched metaphorically in both picture and sound.

Just as The Merry Widow set the bar for editing in musicals, George Stevens’ Gunga Din in 1939 set the bar for editing action and adventure. Not only does the editing follow the physical progress of the scene itself, it also clearly tracks the emotional relationships among the key characters as the action continues. During the first major action sequence — the battle in the deserted village — editors Henry Berman and John Lockert carefully maintain the viewer’s sense of geography as the army squad retreats to the river. At the same time, they inter-cut intricate bits of derring-do with the three sergeants (Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.) exchanging telling glances and reactions.

The editing style proceeds briskly throughout the film’s drama and comedy, yet always hinging around the character interaction. This emotional continuity contributes to the involving build-up and climax at the Temple of Kali in the last third of the film. But Gunga Din’s editors were not nominated for the Oscar. Perhaps the movie’s jaunty high spirits were simply overlooked by the Academy in the wake of the Gone with the Wind sweep (which bestowed Oscars on editors Hal C. Kern and James E. Newcom).

Also shut out of Academy nominations was a remarkable feat of sound recording in 1944 for Preston Sturges’ Hail the Conquering Hero. In the days of mono-track audio, sound recordists Wallace Nogle and Walter Oberst were able to pull off a multi-layered effect with a definition lacking in that year’s winner, the stodgy political biopic, Wilson (Edmund H. Hansen and the 20th Century-Fox Studio Sound Department). In Hero, the sound recordists’ work strongly enhances the pointed comedy of a classified 4-F defense plant worker, Woodrow Lafayette Pershing Truesmith (played by Eddie Bracken), shanghaied by seven real Marines into pretending to be a Marine so he can go home to visit his mother.

Unfortunately, the whole hometown learns of his return and sets up a hero’s welcome for him at the train station. The hero’s welcome involves four bands and five songs — including a diva singing the Marine Corps Hymn — along with the mayor’s speech, which inadvertently cues each of the bands to start playing over each other, as well as over and in between the dialogue introducing townspeople.

Later in the film, Nogle and Oberst also create a rich and realistic sound background over a long single tracking shot following two characters talking as they walk from the town’s business district to its residential area.

For 1955, the Film Editing Oscar went to Joshua Logan’s Picnic (Charles Nelson and William A. Lyon), shot in widescreen and color but, in the same year, it was Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause with James Dean that first fully utilized the possibilities of editing widescreen and color composition for dramatic effect. Perhaps the movie was dismissed in its time as just a picture for teens, so the Academy neglected to nominate William Ziegler for his innovations in editing. But Rebel’s insights into American middle-class society have not dated — nor has Ziegler’s work.

Instead of adhering to the style of standard-frame eye-line, POV and reverse cutting, Ziegler often uses the widescreen perspective to cut into the background. He also cuts on striking colors (reds, greens and blues) to draw the viewer’s eye into the next shot. Other times, he cuts to and from opposing angles that have sparsely composed and densely composed frames. These strategies of editing, explored and modified for each physical setting (police station, suburban home, planetarium) also consistently suggest character relationships and sympathies.

There are many films for which the legendary editor Dede Allen, A.C.E., should have won the Oscar, but Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde stands out. Yet her editing was not even nominated. The award winner for 1967, Hal Ashby, did strong and solid, if not especially groundbreaking, work on In the Heat of the Night. But Allen — influenced by David Newman and Robert Benton’s screenplay and eight years of exposure to the French Nouvelle Vague — took it upon herself to infuse new techniques into mainstream American movies.

From the opening montage of sepia-toned snapshots, a distinct difference from other movies of the time is obvious. Faye Dunaway’s Bonnie is first seen in front of a mirror, turning toward her bed as Allen jump-cuts to her lying down on the bed. Looking up at the brass headboard, Bonnie raises her fist in frustration and the shot jump-cuts to her fist striking it. Later, as we watch a police car chase Bonnie and Clyde’s car fleeing from a bank robbery, Allen cuts in short takes of people back at the bank responding to reporters and being photographed.

The impressionistic montage of brief segments of moments during the fugitive gang’s picnic with Bonnie’s family and the violent finale inter-cutting slow-motion and normal-speed shots also display elements of the new approach to editing that Allen helped bring to Hollywood.

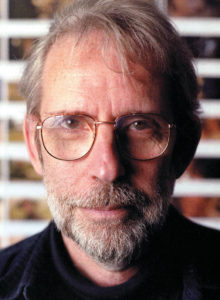

In 1974, Walter Murch, ACE, CAS, MPSE, virtually revolutionized the nature of sound on film with his work on Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation. Credited on the film for sound montage and re-recording mixing, Murch was nominated for Best Sound, along with recordist Art Rochester, but the Oscar was awarded to the very loud Earthquake (Ronald Pierce and Melvin M. Metcalfe, Sr.).

At the time of The Conversation’s release, its elaborate arrangement of sounds must have seemed as rich and complex as that of a major symphonic work of musical orchestration. With the audio surveillance work of the film’s Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) as a central focus, Murch reflects and orchestrates the process of reconstructing the titled “conversation.” He melds, modulates and interweaves electronic noise, mechanical noise, live dialogue, TV sound, recorded music and sounds, and ambient music and sound down to specific and clearly defined noises like the crinkle of paper and the clinking of ice in a glass. But more than simply arranging the sounds as dramatically appropriate for each scene, Murch uses them as thematic and emotional motifs.

Since 1974, the sound editing work on two other films — both nominated for Oscars yet being passed over for others — should also be singled out for expanding on the innovations of The Conversation, each in their own fresh directions.

Nominated for Sound Effects Editing for 1999, David Fincher’s Fight Club lost to a film that was equally skillful in creating a carefully modulated soundscape, The Matrix (Dane A. Davis). But Fight Club’s sound designer Ren Klyce and supervising sound editor Richard Hymns pay extraordinarily precise attention to the particular nuances of how Edward Norton’s narrator hears things. This works dramatically and thematically to heighten the schizophrenic world he shares with Brad Pitt’s Tyler Durden.

Radical shifts in tone from layered depths (whether the sounds of men crying or the sounds of office machines) to minimal or no background noise at all often seem to echo the narrator’s thought processes. Correspondences of sounds from vastly different sources (the lighting of a cigarette lighter fading into a dull explosion) often help to suggest the main character’s continual jumps of logic.

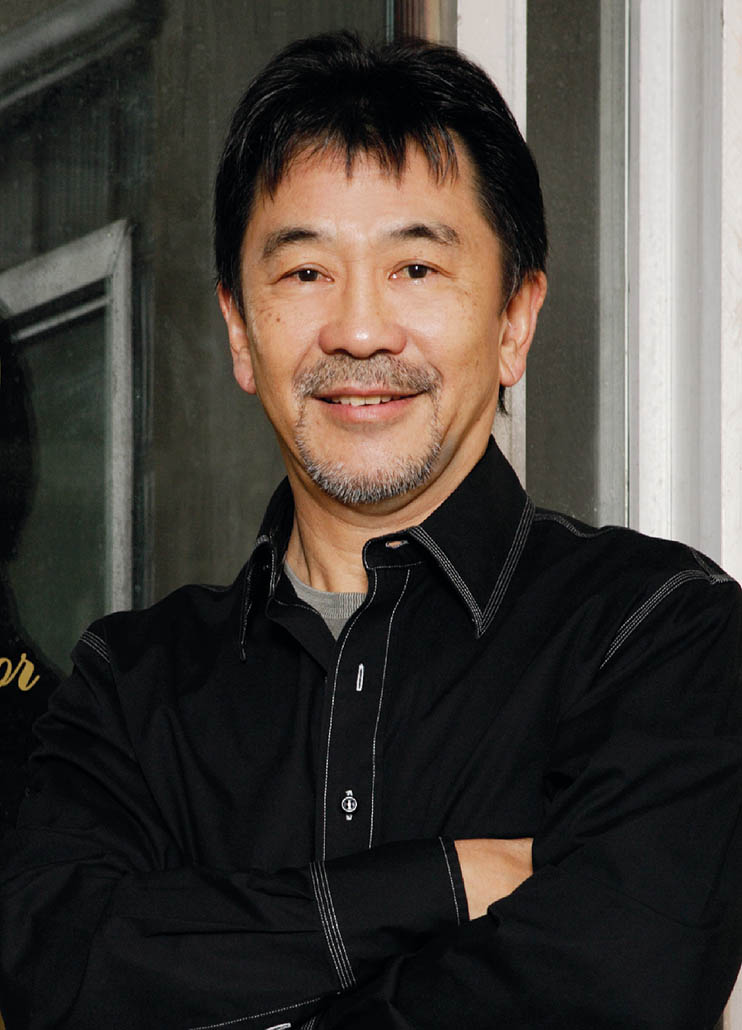

For 2007, the Oscar for what had now come to be designated Sound Editing went to The Bourne Ultimatum (Karen M. Baker and Per Hallberg, MPSE) but Pixar’s nominated feature Ratatouille should have gotten the nod for bringing sound editing in animation to its fullest potential. Sound designer Randy Thom and supervising sound editor Michael Silvers consistently achieve a seamless amalgamation of real-world sounds within the full range of imaginative animation.

Whether shifting from rats speaking to one another in English to humans hearing them squeaking, or incorporating the exaggerated sound effects of over-the-top cartoon antics with the real sounds of a restaurant’s work environment, the sound editing envelops the viewer in the experience. And when Remy, the rat born to be a chef, explains the blending of two different flavors, the sound wondrously creates the cinematic illusion of synesthesia — experiencing the sense of taste as music and color.

But the Academy continued to overlook innovations in picture editing, as well. In 1983, The Right Stuff demonstrated a complex and deservedly acclaimed job of piecing together the epic story of America’s first astronauts and won the Film Editing Oscar for its editing team (Glenn Farr, Lisa Fruchtman, Stephen A. Rotter, Douglas Stewart and Tom Rolf). But Richard Chew, ACE, was not nominated for his work in Paul Brickman’s biting coming-of-age story, Risky Business, in which he devised a fresh style of personal narrative.

Building on how film editing mimics the way the mind pieces together our perceptions, he evokes a consistent and fluid sense of identity with Tom Cruise’s Joel Goodsen. From the opening dream sequence, Chew’s steady rhythm of visuals reveals the issues concerning this upper-middle-class high school senior: getting into a good college and getting laid.

Chew maintains a subtle, rhythmic drive throughout the film, most overtly when Joel dances to Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll” in his living room after being left home alone by his vacationing parents — and more suggestively when he seeks out prostitutes for sex. As Joel’s situation spirals into crisis with an impending Princeton interview, the editing style eases back into the dream-like cutting of the opening, but not for dream sequences. Sometimes using quirky cut-ins to comment on the action, Chew’s work in Risky Business powerfully brings out how the weight of real-life issues are realized as we mature — and are perhaps denied.

Christopher Nolan’s Memento, made in 2001 and edited by Dody Dorn, A.C.E., was at least nominated for Film Editing, but lost to Black Hawk Down (Pietro Scalia, ACE). Maybe it is easier to relate to the graphic horror of war than it is to accept a movie that tells its story backwards as something other than a clever gimmick. But the psychological horror of lying to oneself (the core of Memento) is harder to convey. Exploring the nature of memory itself, Dorn’s editing leads to the ending revelation that conveys that horror.

What begins as an intellectual puzzle builds into startling revelations of characters’ real motivations. The process is highlighted by color sequences moving backward in time that alternate progressively with black-and-white sequences moving forward in time that gradually lengthen. In the end, Memento is a unique cinematic story absolutely dependent on its editing. An Oscar would have been appropriate recognition of that.

For 2004, the Film Editing award went to The Aviator (Thelma Schoonmaker, A.C.E.), a biographical film that effectively laid out the progress of an eccentric man’s erratic career. But, for editing evoking the emotional resonance linking imagination and experience, the Oscar should have gone to Matt Chessé, ACE., rightly nominated for his work on Marc Forster’s Finding Neverland.

The film’s story of how James Barrie (played by Johnny Depp) came to write Peter Pan revolves around the author’s imagination and his relationship with the four young sons of the infirm Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (Kate Winslet). The film’s editing strategy occupies the same revolution.

Early on, Chessé establishes a bond between reality and imagination as he smoothly cuts — often on movements — between Barrie in the park dancing with his huge dog, Porthos, for the boys’ entertainment and Barrie as a ringmaster dancing with a bear in the circus. The cutting between reality and imagination sharpens and diminishes as personal complications and Barrie’s writing progress.

The emotional resolution, foreshadowed and enhanced by the editing, comes near the end when Barrie brings the stage company of the now successful play Peter Pan to the boys’ home. They perform the play in full costume for the dying mother in her parlor that opens out to the real — and imaginary — Neverland in her garden.

As long as Oscars are awarded, the Academy will give us all ample cause to imagine our own Oscar “Should Have Beens.” But, with the clarity of hindsight that allows a better perspective with which to judge often subtle, aesthetic breakthroughs in editing and sound, perhaps the organization can find a way to single out those films of past years that may have been unjustly overlooked.

Whether the Academy recognizes them or not, those (and future) breakthroughs will continue to have their impact on movie storytelling.