by Dan Ochiva

Maybe it’s just a cliché of the East Coast/West Coast division (LA being all about the industry, with New York upholding the true independent spirit), but each of the three veteran editors chosen to present and discuss their work at the New York Post Production Conference this past October are associated with directors far removed from once traditional Hollywood career tracks.

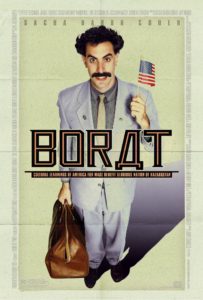

Whether it was Jay Rabinowitz, ACE (Jim Jarmuch’s longtime editor), James Thomas (Borat), or Christopher Tellefsen, ACE (Capote, Gummo), tales of the struggle to pull structure out of tight deadlines and budgets kept conference attendees in rapt silence for the hour-long talk show-style screenings. These keynote presentations, like the rest of the conference, were held in theatres at the 34th Street AMC Cinema, and were moderated by Post magazine consulting editor Ken McGorry and CineMontage editor Tomm Carroll.

The daily keynotes by highly regarded editors made for an effective contrast to the more mundane class sessions held in the theatre. The now annual New York Post Production Conference—three day-long sets of editing and effects classes with a dab of production and Web-related offerings––can sometimes feel like a mind-numbing gloss on the latest software updates, as the multiplex theatre environment precludes hands-on work. But the company behind it, Future Media Concepts, tends to hire smart, quirkily interesting teachers who give out their e-mail addresses to encourage follow-up questions. That’s the right approach when you’re a newbie editor with stars in your eyes after a session with a Rabinowitz, Thomas or Tellefsen.

Indie Icon – Jay Rabinowitz, ACE

Perhaps surprising to some, Jay Rabinowitz still sounds as open and eager as that neophyte he was, a year out of university, who wandered into the production offices of Jarmusch’s Down by Law for his first job. After that apprenticing gig, something clicked. Perhaps the independent path taken by the director clicked with Rabinowitz’s own less typical pass through New York University. After all, he completed the film theory and history-oriented Cinema Studies program, and not the more workaday film production major. In any case, after some other short projects with the director, he notched his first full editing gig with Night on Earth (1991).

Among the half-dozen or so clips shown, Rabinowitz made an interesting selection with a quiet scene from Coffee and Cigarettes (2004), an elegant black-and-white film which Jarmusch made over 17 years during breaks from other projects. An anthology of conversations held over the aforementioned caffeine and tobacco, the various sequences take place among famous, semi-famous and even relatively unknown people, who play themselves.

Only dyed-in-the-wool downtown New York avant-gardistas would recognize the protagonists of the subtly affecting scene Rabinowitz chose. While the actors Bill Rice and Taylor Mead made their reputations via the now historic East Village underground art scene, for the majority of viewers they seemed blank slates, just two old and rumpled figures slumped in their chairs, talking at random as they sit around a table to smoke their cigarettes and drink the bad deli coffee. Rabinowitz’s light touch as an editor shows in the perfectly timed cuts. The pace and mix of shots fit as comfortably as these old friends in real life do as they measure out puffs and sips, creating a quietly elegiac scene that might be an outtake from Waiting for Godot. The editing helps viewers take a seat at the table, with only facial tics, perfectly timed stares and the dozens of barely perceived sound effects guiding us along. For this final scene in the film, Rabinowitz suggested quietly playing an ethereal bit of a Mahler song––used earlier––as some barely heard grace note.

Don’t peg Rabinowitz as only an editor for the avant-garde, however, as he’s handled features for more mainstream directors including Paul Schrader (Affliction), Curtis Hanson (8 Mile), Frank Oz (The Stepford Wives), and even a stint on TV for Barry Levinson (Homicide). But smaller, guerrilla approaches to filmmaking seem closest to his heart, from Adam Bhala Lough’s $50,000-budgeted Bomb the System about graffiti taggers to his ongoing partnership with Jarmusch to work for another independent filmmaking icon, Darren Aronofsky (The Fountain, Requiem for a Dream).

Rabinowitz’s work for another distinctive indie director, Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There, the multi-persona ode to Bob Dylan, was recently released. “It’s a very strange and beautiful film,” said Rabinowitz. “It’s about as far from a Hollywood biopic as you can get.”

Comic Timing – James Thomas

“Strange and beautiful” were probably not the very first words that came to mind to audiences as they flocked to Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006). But the non-stop laughs extracted by this wildly popular mockumentary belie the grueling 11-month post-production process editor James Thomas devised that enabled him to sift through some 620 hours of Varicam footage.

“Avid ScriptSync was a crucial tool,” said Thomas, who relied on the software feature (part of Media Composer) for its ability to phonetically index text and dialogue, synching source clips automatically with the script. That was key to plowing through some 2.5 million feet of HD source material, which was transferred to lower-resolution Betacam for editing. After automating the usual laborious task of synchronization, he could devote more time to presenting each variant of a performance, quickly comparing takes in the context of the overall story arc.

Carefully tracking each and every line of the oft-improvised dialogue was key to director Larry Charles and star Sacha Baron Cohen’s meticulous approach to getting the highest joke-per-minute ratio, according to the editor. “Comedy can’t exist in a bubble while you lock yourself away for months on a project like this,” explained Thomas, who has edited for Baron Cohen for some nine years. Their solution? Extensive test screenings, complete with cameras pointing at the audience, so that Baron Cohen could go through the responses with Thomas line by line the next morning. If the set-up wasn’t delivering, it had to go.

Thomas would then have to figure out the best way to get from one joke’s set up to the next. That became especially complex when he was faced with choosing among up to five camera viewpoints. Charles and Baron Cohen turned to multiple camera set-ups when faced with highly uncontrolled stagings, such as the near riot during the Pamela Anderson book-signing sequence. One or two cameras simply couldn’t offer enough coverage.

Faced with so much footage and so many camera angles, Thomas sought to impose some subtle bits of narrative structure via visual anchors, enough to hold scenes together. “A rather fat guy in a suit turned up in one or two of the cameras [in the Pamela Anderson sequence],” said Thomas. “I then found that the same guy had raced out into the parking lot––he didn’t want to miss what happened to Sacha. I made an effort to include him, as there was something funny about a very proper fat guy charging around, while keeping him involved as an onlooker brought a touch of continuity to the sequence.”

Searching for structure in mounds of documentary material requires patience, of course. But sometimes it just comes from realizing where the best performance exists in even limited amounts of material. “During the initial village sequence, I was faced with two hours of footage where Borat plays an aggressive game of ping pong, but none of it really clicked,” Thomas related. Instead of focusing on the action, the final scene derives its humor from Borat’s antsy bouncing around from foot to foot, waiting for a ping-pong ball that never comes. “We had to keep looking at that sequence for quite some time before we realized that it wasn’t the action that was funny, but [Borat’s] anticipation.”

Thomas honed his craft by editing commercials and music videos (Sting, U2, Prince) in London. But working with comedy became his passion when he moved over to television with his first gig, a 30-minute kids show for the UK’s Channel 4. The pace of a half-hour show, however, doesn’t allow for many subtleties. “I wanted to explore more narrative arcs, not just set up short reaction shots,” said Thomas. After work on other popular British comedy shows including Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends and Red Dwarf, he began his first collaboration with Baron Cohen on the 11 O’Clock Show in the late 1990s, later moving with him to both the British and HBO variants of Da Ali G Show.

But Thomas has kept a hand in editing music videos, this time mixing in stand-up comedy on The Flight of the Conchords, shown on HBO earlier this year. Directed and co-written by Da Ali G Show’s James Bobin, the show features a musical duo from New Zealand who offer deadpan wit and catchy lyrics. True to Thomas’ talents, it’s another show that relies on editing to capture comedic timing. “I love working with live music,” he said.

Eclectic Editor – Christopher Tellefsen

It wouldn’t be hard to see Christopher Tellefsen as someone working from the opposite end of the spectrum from an in-your-face comedy like Borat. After all, the New York-based editor got his start working on Whit Stillman’s urbane comedy Metropolitan (1990).

But Tellefsen, who studied art at New York’s Cooper Union and served for a time as curator of Martin Scorsese’s famed film collection, also edited Harmony Korine’s highly controversial Gummo (1997) and Larry Clark’s just as notorious Kids (1995). Tellefsen handles mainstream projects just as deftly, editing Milos Forman’s The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996), Harold Ramis’ Analyze This (1999), David O. Russell’s Flirting with Disaster (1996), and M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village (2004).

To start off his session, however, Tellefsen chose to highlight the restrained style of director Bennett Miller’s Capote (2005). The film, of course, won Philip Seymour Hoffman an Oscar for his portrayal of author Truman Capote during the years of research and writing for his breakthrough “non-fiction novel,” In Cold Blood.

While it might seem simple to portray the weird reality of an openly gay Southern author from Manhattan kicking around a small Kansas farm community in the early 1960s, getting to the subtle portrayal that Miller sought wasn’t easy. With its low $7.5 million budget (“especially tough if you’re doing a period piece”) and tight 30-day shooting schedule, Tellefsen also knew he had a relatively limited amount of material to work with.

“It was important to get the beginning of the film right,” said Tellefsen. He knew he had strong material for the middle and final portions of the film, but the beginning had to be spot-on to set up the rest.

“At first, we couldn’t figure out how to portray this fish out of water,” he continued. Tellefsen then ran several scenes of early edits from dailies. The cuts between a sparsely populated Kansas in the middle of a dreary winter (Winnipeg, it turns out, looked more authentic) with jump cuts to Capote’s Manhattan milieu were too jarring, and didn’t create their own logic without the prop of a voiceover.

To move the viewer into the story, Tellefsen finally settled on using a cutting rhythm and a similar shot sequence between the initial Kansas scenes and those that show Capote in his typical role of cocktail party raconteur. “It was important to keep viewers in a sort of suspension, for them to not feel like there was a simple conclusion already arrived at,” explained Tellefsen. The re-worked opening scenes also made light use of natural sounds, kept low and at a minimum, with a melancholy piano brought in with the move from the desolate farmhouse to establishing shots of the New York skyline and Capote’s world.

Staying flexible to meet a director’s particular working style is key to Tellefsen’s success with disparate editing challenges. He worked with Forman for 10 months on The People vs. Larry Flynt. “Forman had never worked with digital editing before,” revealed Tellefsen. “I was editing as he was still shooting. I would do four versions of the scene, and he would say, ‘Now show me 10 versions.’” Before finishing that film, he immediately began work on Korine’s Gummo, a film that either pushed beyond the boundaries of acceptable good taste or was a masterpiece, as per Gus Van Sant or Bernardo Bertolucci.

Besides editing the 35mm cinematography of Jean-Yves Escoffier, Tellefsen needed to figure out how to edit in material generated from Hi-8 and Super-8 cameras given to the actors. One solution: shoot all of the non-35mm footage off a monitor, using the screen’s analogue output to meld together the different formats. “To try to keep with the spirit of Harmony’s idea, I had to weave together very different sorts of footage that still had to look like the spontaneous work of one person,” explained Tellefsen. “It needed a light touch––my MO was to not overwork the material.”

In an apt tribute to the venue, each of the editors touched on the need for education. From garnering tips and tricks at a seasoned editor’s side to watching Turner Classic Movies, one has to see and learn constantly. “I’m very happy I studied world cinema,” says Rabinowitz. “Some kids know every movie from the last five years but nothing from before that,” he continued. “It’s important to know that history, because the directors you’ll want to work with know it.”