By Peter Tonguette

Most picture editors know the feeling: You’re in the cutting room working on your current project, and late into the night, you find yourself swept away by a certain scene, performance, or batch of footage.

Oscar-winning editor Bob Murawski, ACE, knows that feeling better than most. Several years ago, Murawski was cutting Orson Welles’s “The Other Side of the Wind,” a legendary Hollywood-set drama starring John Huston as down-on-his-heels veteran director Jake Hannaford and Peter Bogdanovich as rising director Brooks Otterlake. During a production period that lasted from 1970 to 1976, Welles amassed enough material to complete an edit of the film, but legal problems prevented him from doing so prior to his death in 1985. With Murawski seamlessly integrating Welles’s already-cut footage with his own newly edited scenes, Netflix released the film in 2018.

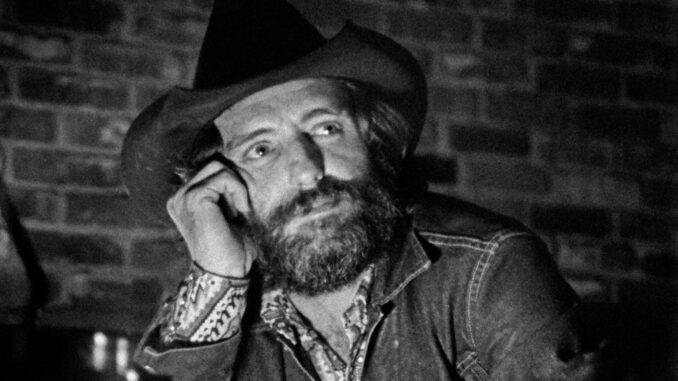

One night, in the thick of his work on the project, Murawski found himself sifting through one of the film’s most talked-about passages: an after-hours conversation between actor-director Dennis Hopper, who died in 2010, and Welles (speaking as himself but also standing in for Huston, who had not yet been hired to appear as Hannaford) in November 1970. Welles intended to pull just a handful of shots of the heavily bearded, cowboy-hat-wearing Hopper, who was to function as a kind of counterculture foil to tough-guy Hannaford. But Murawski found that he couldn’t look away from their full-length dialogue.

“I think I started it at like 10 o’clock one night at the end of a long workday,” Murawski said. “I just found it so fascinating and incredible that I think I was there until 1 or 2 in the morning.”

This month, audiences will have a chance to view the conversation that so captivated Murawski with “Hopper/Welles,” which presents the unexpurgated interview between the director of “Easy Rider” (1969) and the auteur of “Citizen Kane” (1941). The film, which was unveiled this month at the Venice Film Festival, will next be shown at the New York Film Festival. (The producers are currently seeking an American distributor.) As he did on “The Other Side of the Wind,” Murawski served as the project’s editor.

In preparing “The Other Side of the Wind,” Murawski followed Welles’s wishes to include just a moment here, a moment there, from the Hopper interview. “Like the rest of the movie, the interview footage was really chopped up because Orson had gone through it at some point and pulled out selects,” Murawski said. “Sometimes it was individual lines of dialogue, but a lot of times it was just a laugh, a nod, a puff of a cigarette — little cutaway pieces that he thought he would use when he put together that fake interview with Hannaford.”

Thinking ahead, though, Murawski made an assembly of the entire interview with Hopper, along with similar interviews Welles conducted with other contemporary filmmakers that were intended to be excerpted in “The Other Side of the Wind” (including Paul Mazursky and Curtis Harrington). “I put together a basic edit so we would have a starting point if somebody ever needed it,” Murawski said.

Producer Filip Jan Rymsza said Murawski’s initial assembly was set aside while the team focused on completing “The Other Side of the Wind.”

“We had it assembled — all nine reels — and that’s how it existed,” Rymsza said. “Bob and I watched it, we thought it was interesting, but, obviously, with that amount of footage, and with our focus just on ‘The Other Side of the Wind,’ we really didn’t give it too much thought.”

That changed earlier this year when Rymsza received interest from the Venice Film Festival in screening the material that would become “Hopper/Welles.” “He had shown them some of the footage, and they were very excited about it,” Murawski said. “Actually, they said, ‘Just send it to us like this — you don’t even need to do anything.’”

Instead, Murawski dove back into the material, which was neither shot nor conceived to run as a continuous documentary. To start with, there was the problem of Welles himself: He was never meant to appear in “The Other Side of the Wind.” So, although cinematographer Gary Graver oversaw two cameras shooting simultaneously, neither was trained on Welles. Meanwhile, since no microphone was on Welles either, sound designer and re-recording mixer Jussi Tegelman was tasked with making the director’s off-mic dialogue come through with maximum clarity.

Since he intended to pluck stray bits and pieces from the interview, Welles paid little attention to intrusions such as slates or camera operators becoming visible behind Hopper, who is dramatically seated in front of a blazing fire in a fireplace. “Orson even says, ‘Hey, don’t be shy about putting the slate in,’” said Murawski, who included such moments in his cut. “Whenever the camera needed a slate, just jam it in and do it, because he knew it was important to keep the stuff in sync. It was all very practical and pragmatic in terms of the way it was shot.”

“There are a lot of times where both cameras are roaming around, trying to find a better shot,” Murawski said. “You could get a good piece of Hopper backlit or a close-up of his eyes or taking a puff of the cigarette or just little cinematic shots.”

When film ran out in both cameras at once, Welles and Hopper would sometimes continue to converse, forcing Murawski to swap in other footage to bridge the gaps. “It was kind of finding shots of Hopper from behind where you couldn’t see his mouth or wider shots,” Murawski said. “I felt very much at liberty to do that because that’s what Orson would’ve done. Orson was the king of cheating in dialogue where it didn’t fit and redoing dialogue and faking in pieces.”

Even so, “Hopper/Welles” more or less unfolds in the order in which it was shot, with Welles “warming up” Hopper early on before taking deep-dives into subjects ranging from 1960s-era political activism to filmmaking techniques. There was some talk among Rymsza and Murawski of shortening the 130-minute “Hopper/Welles” into something closer to 90 minutes, but Murawski felt that the interplay between the two filmmakers was sufficiently fascinating to sustain the final length.

“Ultimately, I just felt that different people are going to respond to different things,” Murawski said. “Maybe the political stuff somebody will find more interesting, the movie stuff somebody will find more interesting. . . . Some of that stuff could’ve easily come out, but all those things were somebody’s . . . favorite part of the movie.”

Yet “Hopper/Welles” has cinematic qualities beyond the mere content of the back-and-forth between the two men. Shooting in shimmery black-and-white, cinematographer Graver used kerosene lamps for lighting — in “The Other Side of the Wind,” the material was intended to accompany a sequence in which Hannaford’s electricity goes out — which surprised Hopper when he showed up for the interview. “Even a filmmaker as experimental as Dennis Hopper was amazed by this,” Graver, who died in 2006, recalled in his memoir Making Movies with Orson Welles. “Films just weren’t lit that way. But we did it and it worked wonderfully. That scene looks terrific.”

Murawski also chose to retain the background sound of a chiming clock at one point during the interview — a perfect touch for a Welles film, since the director considered his own best directorial work to be his Shakespeare-based masterpiece “Chimes at Midnight” (1966). “When Filip and I heard the grandfather clock chiming, it really made it seem like it was this long thing where they were talking late into the night,” Murawski said. “It made it seem so intimate.”

In the end, Murawski considers “Hopper/Welles” to be the ultimate “found footage” movie—from the ashes of “The Other Side of the Wind,” the editor was able to construct a new standalone movie. It just goes to show you that every bit of footage shot for a movie is worth scrutinizing — even very late into the night.

“It was just outtakes and scraps, basically,” Murawski said. “Who can believe that it’s actually become a bona fide feature?”