by David E. Fluhr, CAS

Things are not always what they originally appear to be. Throughout life, our experiences shape our personal growth. As we revisit a film, re-read a book or listen to a musical piece over and over, our eyes and ears open up to new interpretations. This actually happened to me multiple times over many years––with the same film.

When I first watched Forbidden Planet on TV, I was maybe 12 years old. I became absorbed in the story, and the “sound” of the film. I was terrified by the concealed creature representing the id (the subconscious dark side) of Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon). It was unstoppable and inescapable––and ultimately could destroy us. The creature appears in a vague outline form accompanied by music and sound effects and was very effective in keeping me from sleep for more than a few nights. Eventually, my interest moved from scary monsters to the soundtrack and the deeper meaning of the story.

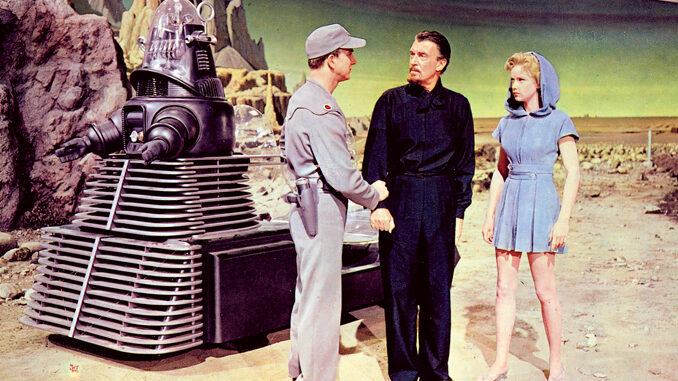

The film tells the story of a 23rd-century starship crew on a rescue mission to the planet Altair-4. Led by Commander J.J. Adams (Leslie Nielsen), they arrive to find all but two of the colonists dead: Morbius and his daughter Altaira (Anne Francis). There is much mystery as Morbius warns of the “forces” on the planet that will destroy the crew. We also meet the now famous Robby the Robot, who handles various chores for Morbius. Based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest (see related story, page 36), Forbidden Planet was envisioned as a “B” sci-fi film, a growing genre in the 1950s. Directed by Fred Wilcox, edited by Ferris Webster and released by MGM in 1956, it was Oscar-nominated for Best Effects and Visual Effects, and garnered much praise.

During my high school days, I studied 20th-century music composition. When I entered college, majoring in electronic com- position, I was exposed to many com- posers, including experimental composer John Cage. While studying Cage, I discovered that the musical score of Forbidden Planet was created by the husband-and-wife team of Bebe and Louis Barron, who had studied music composition in the 1940s and collaborated with Cage. They pioneered what we would today call synthesized music, nearly 10 years before the invention of the Moog synthesizer. Louis created electronic “circuits,” which made the sounds, and Bebe edited them together into musical form. After their work with Cage, they were asked to provide the musical score for Forbidden Planet––just the haunting feeling a sci-fi space film would need.

They used ring modulation, plate reverbs, speed variations, reversing, cutting and splicing, as well as musique concrete––taking sounds recorded in the real world on their primitive tape recorder and changing them into musical phrases. These were techniques I was studying, and I used their soundtrack to the film as a learn- ing tool.

An interesting footnote is that their film score was credited as “Electronic Tonalities.” It was controversial at the time, as it was not eligible to be entered as a musical score at the Academy Awards. But the sound of the film was unlike anything audiences had heard before. The music is almost always present, and used with sound effects for space ships, backgrounds, etc. Its effect on me was invaluable, as I became aware of sound for picture. I moved to Los Angeles after college, and learned the craft of sound editing and mixing using my musical background, as many of us do in film sound re-recording.

In 1999, I attended a screening and panel discussion of Forbidden Planet, hosted by Star Trek’s George Takei (the film was one of Gene Roddenberry’s inspirations for Star Trek). On the panel were actors Anne Francis, Warren Stevens, Richard Anderson, Earl Holliman and composer Bebe Barron. Watching the film on the big screen, with the beautiful Cinemascope picture and restored sound was one thing. But now, with adult eyes and ears, it was a new experience yet again. The audience laughed hard during some scenes. This struck me dramatically because my memories of the scary monster and my terror had skewed my outlook. Also, the dialogue contained plenty of racy innuendo and “adult” topics!

Recently, I watched the film with my 10-year-old son. He covered his eyes during the scary (and romance) parts, and missed all the innuendo as I had years before. In the end, the film was all of these things––serious, funny, corny, scary and thought-provoking.

Alas, the ancient civilization on Altair-4 had advanced its technology too far in its quest for perfection. It was eventually destroyed by the fact that, “We are, after all, not God”––the final line of the film.