by Ray Zone

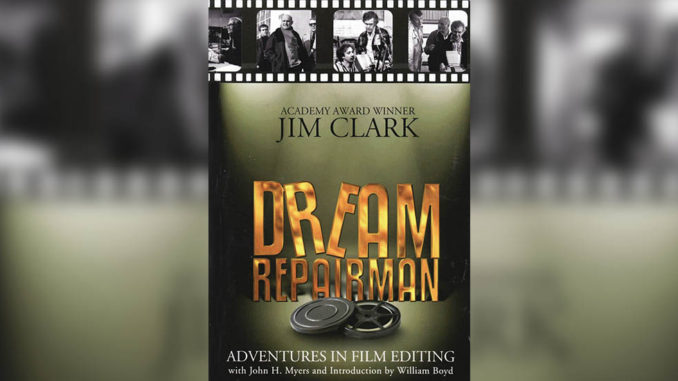

Dream Repairman

Adventures in Film Editing

by Jim Clark with John H. Myers Introduction by William Boyd

311 pps., paperbound $24.95

ISBN: 978-0-9797184-9-6

I’ve been a film editor for more years than I care to remember,” writes Jim Clark. And though he has tried his hand at directing and writing, “It’s in the cutting rooms that I’ve made my most substantial contributions,” he claims. With this engaging and highly entertaining autobiography, Clark recounts an illustrious career as an editor on films like The Innocents (1961), Charade (1963), The Killing Fields (1984; for which he won an Academy Award), Marathon Man (1976), Midnight Cowboy (1969) and The Jackal (1997), and working with directors such as Jack Clayton, Stanley Donen, Roland Joffe, Michael Caton-Jones and John Schlesinger.

There are not many autobiographies written by film editors. Maybe this is because “most good film editors remain unknown to the public,” observes Clark. “This in no way diminishes the role they play in the success or failure of the finished product. We remember Alfred Hitchcock but not George Tomasini. We know Howard Hawks but not Christian Nyby, and on it goes.” We can be grateful that Clark has expended the effort to recount his career as an editor in motion pictures, sharing many war stories that are very amusing. He acknowledges that his book “won’t teach you much about film editing. I’m not certain you can learn such skills from a book. Editing film is really a combination of instinct and experience––with a lot of experimentation thrown in.”

Clark began his professional career at Ealing Studios, which he characterizes as “a microcosm of British society, reflected in the pictures they made.” Sir Michael Balcon, like a great headmaster of a school, presided over the studio and was responsible for Ealing’s rise and fall. “The studio was class-ridden,” recalls Clark. “You knew your station and stayed in it or incurred wrath in high places.” Clark’s duties were largely centered around the rewinder, and he had to learn how to use the Bell & Howell foot joiner, “a massive iron pedal-operated device. This was a machine you had to respect or it would have your fingers.”

“Without the material, we can’t do a thing. We are only interpreting what we’re given.” – Jim Clark

Soon, Clark moved into sound. His descriptions of technical progress in sound and picture editing throughout his career provide a nice capsule history of the evolution of editing technology. He recounts, for example, the painstaking efforts necessary with “blooping ink” applied to optical sound edits in the days before magnetic sound editing. “If you didn’t bloop the join” with a triangle of opaque black ink on the optical track of the film, “it would make a popping noise.” When the sound mix was balanced and director-approved, they would go for a take. Tension increased because mistakes would subsequently be costly. “Being a sound mixer in those days was ulcerating, though, if a reel had been going well before errors were made, the good section could be saved and used, since it was possible to neg cut the final mix too.”

Intermittently, Clark incorporates a flashback section in his narrative. These are recollections of his school years and they provide illuminating glimpses of his lifelong passion for cinema. As a schoolboy at the Oundle School, for example, Clark founded the Oundle Film Society in 1947, an organization that continues to this day. Sixteen-millimeter prints of films were rented initially, and then two 35mm projectors were installed at the school. These early experiences in cinema and the handling of film and projectors served the editor well in his subsequent career.

Clark’s descriptions of the different methodologies of directors like Clayton and Donen is highly informative. Working with Clayton on The Innocents, Clark found the director to be “a perfectionist who left nothing to chance and was very precise in his approach to work.” Stanley Donen, however, “shot Charade in a perfectly straightforward manner” with coverage of entire scenes in long shot, medium shot and close-up without moving the camera. “These dialogue scenes were entirely made in the cutting room,” writes Clark. “We also line cut a good deal to reduce the scenes and make them sharper.”

Working on Charade, Clark picked up some little tricks of his own. “For example, I would never let a character shut a door, allowing him to start to move the door, but having the sound of the closing off-screen. Later on, I developed this more, so that actions––once begun––were very rarely completed.” Clark is not a fan of some present-day editing techniques. “I am still averse to overcutting and deplore the pernicious influence of commercials and pop videos on feature films,” he notes.

When he received the Academy Award for editing The Killing Fields, Clark was disturbed that director Roland Joffe had not been nominated. “I’ve always been concerned when editors get awards and directors don’t,” he declares. “It seems wrong to me because without the material, we can’t do a thing. We are only interpreting what we’re given. We are the dream repairmen. That’s what we do. We repair other people’s dreams.”