By Betsy A. McLane

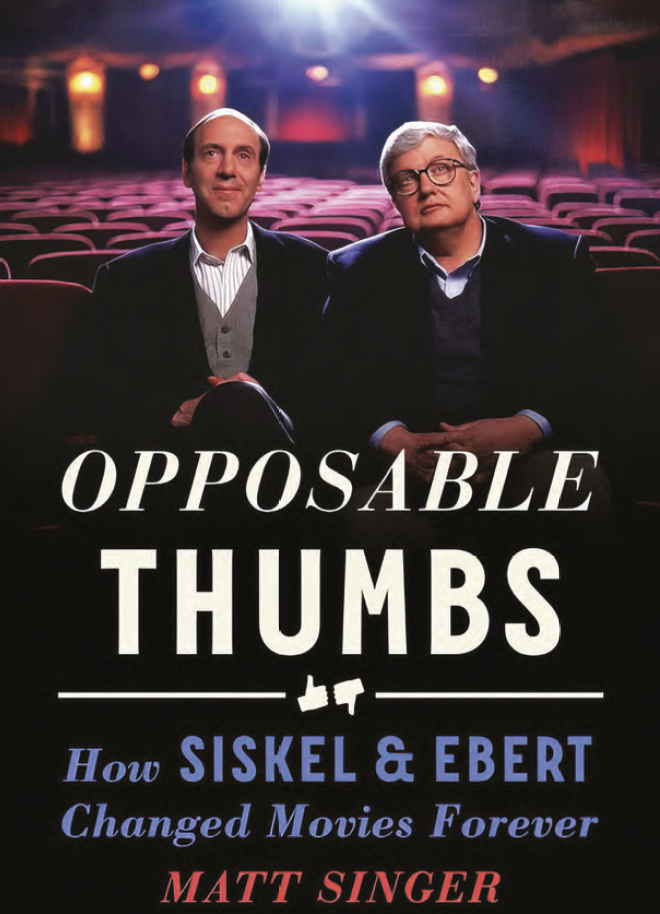

Reviewing movies with a “thumbs up/thumbs down” gesture might bring to mind the fate of ancient gladiators in the Roman Colosseum. It is definitive and dramatic. But for many years beginning in the 1970s, For many years beginning in the 1970s, other thumbs, belonging to film critics Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, were watched by more people than any Roman Emperor’s. Their decisions carried weight with the moviegoing public, but whether they meant life or death for a film is debatable. Matt Singer’s book, “Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel and Ebert Changed Movies Forever,” attempts to prove that Siskel and Ebert’s thumbs determined the fate of many movies.

Consider that this is a review, by a reviewer, of a book written by a reviewer, about two other reviewers: meta-criticism. Meta-criticism is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “Criticism of criticism; that is the examination of the principles, methods and terms either in general, or [as in this case] the study of particular critics or critical debates.” “Opposable Thumbs” parses in extraordinary detail the lives and work of film critics Siskel and Ebert. Singer is himself a film critic and currently chair of the New York Film Critics Circle. Singer’s critical stance can be assessed by looking at his other book, “Marvel’s SpiderMan: From Amazing to Spectacular-The Definitive Comic Art Collection,” co-authored with J. M. DeMatteis. Singer is also the editor and film critic at Screen Crush, a movie fan site. Singer is concerned with the popular, hence an emphasis on superlatives. “Spectacular,” “definitive” and “favorite” are large claims. This perspective may be a good starting place to write about men who were the most visible critics in U.S. television history, but such adulation casts a skeptical light on any claims of “Forever.”

If meta-criticism sounds too highfalutin an approach to a book about two well-liked 20th century American newspaper writers and television personalities, consider the grandiosity of its subtitle. Before the cover is opened, the subtitle makes clear that Singer is a fervent fan of the movies, and of these men. This is confirmed by a tone of respectful eagerness that wafts through every page. Singer’s attention to specifics is admirable, but at times the deluge of names, dates, and numbers is overwhelming, especially when listened to in audio form. Nostalgic fans of Siskel and Ebert may be the only readers to welcome all this detail.

“Opposable Thumbs” is especially good at explaining the various origin stories of “At the Movies,” the first incarnation of a movie review television show featuring Siskel and Ebert. Many people were involved with the idea for a program that would feature the film critics of Chicago’s two rival newspapers. Ebert worked at the Chicago Sun Times for 47 years, winning a Pulitzer Prize along the way. Siskel wrote for the competing Chicago Tribune, and the two were fierce rivals. While several individuals could lay claim to having thought up the show, it was Thea Flaum, the co-producer of “At the Movies,” who transformed the failure of the show’s pilot into a success by grooming two newspaper men into television personalities. Singer gives her due credit, noting that without Flaum, there would be no “Siskbert.”

Siskel and Ebert were popular, not for their erudite analyses but because of who they were, and especially who they became when they were together. Viewers tuned in to their shows partly for the reviews and partly for the film clips. At that time, clips were not universally available and had to be edited by the show’s staff from actual reels of film to help bolster the reviews. But what really captivated audiences was the verbal sparring between the two men, who at least at first openly disliked each other. When Siskel scooped Ebert and landed a choice interview, Siskel would say, “Take that, Tubby.” In time, they developed a respectful friendship, and Siskel’s daughters were flower girls at Ebert’s wedding to Chaz Hammel in 1992.

While the book covers their entire careers, it focuses on the 1970s and 1980s when the two were at the peak of their popularity and, as Singer points out, “The New Hollywood” was sucking attention away from traditional studio fare. Films by young directors Steven Spielberg, Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, Francis Coppola, Henry Jaglom, Michael Cimino, John Cassavetes, Joan Micklin Silver, and others filled the screens with new ideas and controversial material. Siskel and Ebert encouraged that “New Hollywood” energy. An appendix offers a list of films that the duo championed over the years but which never resonated with a wide audience. Although not all are listed by Singer, these included “Personal Best” (1982, dir. Robert Towne), “Cattle Annie and Little Britches” (1981, dir. Lamont Johnson), “Swamp Thing” (1982, dir. Wes Craven), “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge” (1990, dir. James Ivory), and “Brother’s Keeper” (1992, dir. Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky), among others.

While the book covers their entire careers, it focuses on the 1970s and 1980s when the two were at the peak of their popularity and, as Singer points out, “The New Hollywood” was sucking attention away from traditional studio fare. Films by young directors Steven Spielberg, Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, Francis Coppola, Henry Jaglom, Michael Cimino, John Cassavetes, Joan Micklin Silver, and others filled the screens with new ideas and controversial material. Siskel and Ebert encouraged that “New Hollywood” energy. An appendix offers a list of films that the duo championed over the years but which never resonated with a wide audience. Although not all are listed by Singer, these included “Personal Best” (1982, dir. Robert Towne), “Cattle Annie and Little Britches” (1981, dir. Lamont Johnson), “Swamp Thing” (1982, dir. Wes Craven), “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge” (1990, dir. James Ivory), and “Brother’s Keeper” (1992, dir. Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky), among others.

Siskel would get a scoop and tell Ebert: ‘Take that, Tubby.’

“Opposable Thumbs” also includes juicy trivia like Gene Siskel’s fascination with “Saturday Night Fever” (1977). Eventually seeing the film 17 times, the critic was apparently able to harangue director John Badham about continuity errors. Siskel purchased one of John Travolta’s suits from the film at a charity auction in 1978 for around $2,000 — and he sold it at a Christie’s auction in 1995 for $145,000.

Singer tries hard to make the case for Siskel’s and Ebert’s importance, and he succeeds in establishing the widespread fondness audiences had for their decades-long TV shows. He does an impeccable job of corralling thousands of facts, dozens of people, and hundreds of interviews and reviews to write what is, for now, the definitive book on Siskel and Ebert. The popularity of the two is undeniable, especially once their show went into syndication in 1982 as “At the Movies”; the title was soon changed to “Siskel & Ebert at the Movies,” and then simply to “Siskel & Ebert.” After Gene Siskel’s death at age 53 in 1999, Ebert continued with a variety of partners, but the bristling chemistry that made must-see television out of two verbally sparring men was gone.

The shows’ thumbs up/thumbs down reviews may have affected the box office success of some films — or the careers of a few filmmakers. Perhaps the most dramatic example was Roger Ebert’s support for the feature documentary “Hoop Dreams” (1994, dir. Steve James). As he wrote, “’Hoop Dreams’ … is not only a documentary. It is also poetry and prose, muckraking and expose, journalism and polemic. It is one of the great moviegoing experiences of my lifetime.” Ebert was part of the charge against The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences when “Hoop Dreams” was not nominated for an Oscar, an omission that contributed to a complete revamping of the Academy’s documentary nomination process. While Siskel also felt that a nomination was justified, he more practically stated that the controversy, stemming from distributor Ira Deutchman, helped make the film financially successful. Their admiration for this film was likely increased by the fact that the film’s subjects and filmmakers, like Siskel and Ebert themselves, came from Chicago.

Critics have not and do not change movies forever. While the popularity of Siskel and Ebert on television made them powerful national influencers, claiming that one (or two) critics could change the long-term course of movies is not a credible argument. Criticism of any form is by nature a reflection of the critic who is writing. Whether consciously or not, consumers learn about the biases and thought processes of critics whose opinions they read consistently. This makes almost all criticism self-reflexive. “Opposable Thumbs” and this book review are, in this sense, self-reflexive. Whether consciously or not, consumers can see between the words and come to know something about who is writing or speaking. They sometimes sense as much about the critic as they learn about the film under consideration. “Opposable Thumbs” offers a brief overview of the history of film criticism in the U.S. but does not go far enough in its contextualization of the show within that history. Singer also ponders the demise of known authorial criticism in the current era of instant public analysis. The overload of opinions about any film can make it hard to trust anyone. If anyone retains some of the power of a critical voice today, it might be long-time writers at The New York Times, and on a popular scale, Leonard Maltin.

The best critics have gravitas because of their subjective opinions. For a time, Siskel and Ebert had this gravitas because they were the most widely known film critics in the U.S. The intelligentsia might quote The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael or laugh at Gene Shalit’s pun-filled reviews on “The Today Show,” but in an era before anyone could become an internet film critic, Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel possessed two important thumbs. Matt Singer provides a valuable record of their work, but his glorification of the men ultimately reveals as much about him as it does about films and film criticism.

“Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel and Ebert Changed the Movies Forever”

By Matt Singer

352 pages

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2023