By Peter Tonguette

The late filmmaker William Friedkin was fond of describing his 1973 horror masterpiece “The Exorcist” as being a meditation on “the mystery of faith.”

Undoubtedly, religious conviction — and its lack — is at the heart of the story of 12-year-old Regan (Linda Blair), the precocious but well-adjusted daughter of divorced actress Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn) who unaccountably undergoes severe behavioral changes — and, during several famous sequences, gravitational changes — that are eventually attributed to demonic possession. A neurotic Jesuit priest, Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller) is put on the case, and in ecclesiastical partnership with a battle-seasoned exorcist, Father Lankester Merrin (Max von Sydow), liberates Regan and confirms his own, previously dubious faith.

Yet the “mystery of faith” isn’t the only mystery that hovers over “The Exorcist.” Perhaps the biggest unsolved question is how such an unlikely project became not only one of the genuine box-office sensations of the 1970s but the cornerstone for a seemingly endless succession of sequels, prequels, reboots, imitators, and outright copycats?

In an engaging and enlightening new book about the “Exorcist” franchise, veteran entertainment journalist Nat Segaloff establishes the many challenges, stumbling blocks, near-misses, and even occult occurrences that might have derailed the film. Consider the literary background of screenwriter and producer William Peter Blatty, who was a serious and committed Catholic but who, until writing the novel upon which the film was based, had proven himself only as a writer of comedies. No less uncertain was the film’s casting, special effects, editing, and music, any one of which could have derailed the whole enterprise.

Then there were the ominous on-set occurrences, including a stage that was consumed by fire, a severe back injury experienced by Burstyn following an ill-advised stunt, and the death of supporting actor Jack MacGowran within weeks of the completion of his scenes. “Such negative energy in that film!” said Shirley MacLaine, a longtime crony of Blatty’s on whom the writer based Chris MacNeil (but who was ruled out for a role in the film). For her part, Burstyn put it this way: “We were calling on some very heavy energy. People might say dark forces, but that might be too dramatic. I don’t think you fool around with those kind of energy fields without having some sort of manifestation, and we had a lot.” Even so, the film was a gigantic commercial success whose intellectual property is still being harvested — see, for example, this fall’s release of David Gordon Green’s “The Exorcist: Believer”— and whose behind-the-scenes stories remain fascinating enough to produce a book such as this one.

Then there were the ominous on-set occurrences, including a stage that was consumed by fire, a severe back injury experienced by Burstyn following an ill-advised stunt, and the death of supporting actor Jack MacGowran within weeks of the completion of his scenes. “Such negative energy in that film!” said Shirley MacLaine, a longtime crony of Blatty’s on whom the writer based Chris MacNeil (but who was ruled out for a role in the film). For her part, Burstyn put it this way: “We were calling on some very heavy energy. People might say dark forces, but that might be too dramatic. I don’t think you fool around with those kind of energy fields without having some sort of manifestation, and we had a lot.” Even so, the film was a gigantic commercial success whose intellectual property is still being harvested — see, for example, this fall’s release of David Gordon Green’s “The Exorcist: Believer”— and whose behind-the-scenes stories remain fascinating enough to produce a book such as this one.

To be sure, the drama surrounding the making of “The Exorcist” has been amply recounted in innumerable documentaries and making-of featurettes, but Segaloff is an author uniquely well positioned to retell well-trod stories fully and well. The author of an earlier biography of Friedkin, Segaloff had firsthand access to both the famously mercurial and volatile filmmaker as well as to writer-producer Blatty, and his own involvement with the release of the original film renders him an eyewitness to its iconic status: In 1973, the year that the picture was released, Segaloff was working as a publicist for the Sacks Theatres chain in Boston.

“Ticket holders waiting in line for the next performance would see the distressed faces of those leaving and pump themselves into a frenzy even before the lights went down,” Segaloff writes of the initial, admittedly over-the-top audience response to the film. His own reaction was more measured but no less appreciative. “I tried to understand why people of faith seemed disturbed in ways that other people were not,” he writes. “I also saw that the artistry and thought that went into the film were genuine.”

In a series of swift, well-delineated chapters, Segaloff maps out the backstory, production, and still-ongoing legacy of “The Exorcist.” Arguably the Rosetta stone of the project is a 1949 newspaper article about an alleged exorcism that caught the attention of a young Blatty, then a student at Georgetown University. Raised in the Catholic Church, Blatty strayed from his faith only in the strictly professional sense: instead of becoming a priest, as was expected of this last-born of five children, he became a comic novelist (“I, Billy Shakespeare”) and screenwriter traded in farces, including Blake Edwards’s “A Shot in the Dark” and “Promise Her Anything,” starring Warren Beatty and Leslie Caron.

Yet Blatty’s faith remained with him, even if only scant traces could be discerned in his work up to that point. But in 1969, he was still profoundly distraught by the death of his mother two years earlier. “I would say in my case, my grief could be described by an outside observer as neurotic [and] overdrawn,” he said. In response to his grief, Blatty remembered the real-life exorcism he had once read about and set about fictionalizing it for his first non-comic novel, “The Exorcist.” By his lights, the novel would not only be a gripping, chilling tale but would achieve something even more profound: prove the existence of a higher power. “Here, at last, was tangible evidence of transcendence,” Blatty said of the real-life case. “If there were demons, there were angels and probably a God and a life everlasting.”

Proof of a higher filmmaking power, at least, may be discerned in the numerous bits of chance and coincidence that helped get the movie made, including Blatty’s initial instinct to hire Friedkin, who, at the time that the manuscript for “The Exorcist” was being circulated, was completing what would be his breakthrough film, the Oscar-winning “The French Connection.” In seeking Friedkin’s services, however, Blatty was not merely latching onto the directorial flavor of the month but following his gut. Years earlier, when he was still in the employ of Edwards, Blatty had crossed paths with Friedkin, who had reacted unfavorably to a script Blatty penned for Edwards — a script about which Blatty shared Friedkin’s low opinion. Holding the director in high regard for his rather merciless honesty, Blatty came to believe that Friedkin could make “The Exorcist” into an authentic and believable film.

Crucial to that believability was the film’s casting. Although superstars such as Paul Newman and Jack Nicholson lobbied for the part of Father Karras — and Stacy Keach had been cast in the role — Friedkin would hear of no one but Jason Miller, a Catholic University of America-educated playwright who had the manner and countenance of a man of the cloth. Meanwhile, the search for a young thespian to play Regan had largely been a frustrating, fruitless affair until the almost-accidental discovery of Linda Blair. “There came a time when I thought we were not gonna be able to make this film with a twelve- or thirteen-year-old,” Friedkin said, but when Blair’s mother arrived unannounced with her daughter in tow, the director had the foresight to agree to see her — another miracle, at least of the casting gods? Casting Max von Sydow as Father Merrin was comparatively straight-forward, although the Swedish actor made no bones about the fact that he did not share his on-screen character’s religious convictions. Although he had been cast as Jesus in George Stevens’s “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” von Sydow told Friedkin, “I played Jesus, but I didn’t play him as a Christian, I played him as a man.”

In Segaloff’s telling, the editing of the film was its own series of trials. The supervising film editor of record was a newcomer named Jordan Leondopoulos (whose scant subsequent screen credits go no further than 1981), but the bulk of the editing fell to Norman Gay, Evan A. Lottman, ACE, and Bud Smith, ACE. Ruthless with his own work — and, by extension, Blatty’s — Friedkin lopped off a number of scenes during post-production, including Regan’s “spider walk” down a flight of stairs and a theologically weighty discussion between Karras and Merrin. Blatty never reconciled himself to these cuts, and by the turn of the millennium, he had managed to cajole Friedkin into reinstating them. Prepared by Friedkin’s then-regular editor Augie Hess, this cut was dubbed “The Version You’ve Never Seen” when it was released in theaters in 2000. “The first thing to say is that it is not the director’s cut,” said film critic Mark Kermode. “If anything, it is the writer’s cut.” Burstyn was opposed to the after-the-fact tinkering. “I like the original the way it was,” she said.

As would become typical for a Friedkin production, the soundtrack was given enormous scrutiny. Volunteering to drink, smoke, and consume raw eggs to sufficiently distort her voice, legendary actress Mercedes McCambridge was called in to dub the lines spoken by the demon-possessed Regan; McCambridge’s voice, in turn, was further augmented by “the squeals of pigs being led to the slaughter, voices played backwards, different microphones, and various levels of distortion on the combined tracks.” Famously, a score by Lalo Schifrin did not pass muster with Friedkin — “He took the roll of [sound] film, took it out in front of Todd-AO, right in the street, and just threw it into the parking lot,” recalled editor Smith — but providence was on his side when he happened upon an eerie recording by Mike Oldfield titled “Tubular Bells,” the sounds of which are still synonymous with the film.

Perhaps the various on-set accidents and strange goings-on suggest that “The Exorcist” was a cursed film — or, as Burstyn put it, one that was interfering with nefarious energies — but it’s clear from its many strokes of creative good fortune that it was also a blessed one. Certainly the executives at Warner Bros. had reason to be thankful: on its original release, the film grossed $193 million. Yet if the public responded to the picture, a cadre of Hollywood old-timers felt it was an example of how far their industry had fallen. Although the film was nominated for 10 Oscars — including Best Picture, Director, Actress for Burstyn, Supporting Actress for Blair, Supporting Actor for Miller, and Editing — veteran director George Cukor is said to have proclaimed: “If this thing wins an Academy Award it’s the end of Hollywood.” (The film walked away with two Oscars: Best Adapted Screenplay for Blatty and Best Sound for Robert Knudson and Christopher Newman.) Yet despite its excesses, shock effects, and occasional gross-out moments, the film is notable for having by and large honored the seriousness with which Blatty first undertook the project. “I didn’t set out to scare the hell out of people as you do with a horror film,” Friedkin said. “I set out to make a film that would make them think about the concept of good and evil.”

“Cursed,” however, might very well be the right word to describe the subsequent entries in the “Exorcist” canon, most of which were beset by post-production drama. In 1977, John Boorman made as his follow-up to his masterpiece, “Deliverance” (1972), the first sequel to “The Exorcist,” “Exorcist II: The Heretic.” This highly imaginative, ostentatiously stylized film has long had admirers in high places — New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael wrote that “the picture has a visionary crazy grandeur (like that of Fritz Lang’s loony ‘Metropolis’)” — but Boorman’s initial 117-minute cut prompted fierce audience blowback. “I saw this film at a night-before preview, and the audience started laughing at the movie well before I was inclined to,” said film scholar Tim Lucas. The perception that the film was a stinker was so pervasive that Warner Bros. compelled Boorman to make post-release cuts that resulted in a 110-minute running time. “Whatever [the audience] laughed at, he cut,” Segaloff writes. “Some of the excised footage made it into the final version eventually released on home video, some did not.” Reflecting on the experience, Boorman said: “The sin I committed was not giving them what they wanted in terms of horror. There’s this wild beast out there which is the audience. I created this arena and I just couldn’t throw enough Christians in it.”

Thirteen years later, Blatty, who had not been involved in “Exorcist II,” agreed to transform his novel “Legion” into “The Exorcist III,” but the project was betwixt and between: although “Legion” had featured characters from “The Exorcist,” it was in no way an obvious continuation of the earlier story. Executives from Morgan Creek were dismayed. “The problem, the company realized, was that a film with the word ‘exorcist’ in the title needed an exorcism,” Segaloff writes, pointing to $9 million worth of rewrites and reshoots that included the fantastical notion of Jason Miller (Father Karras in the original film) being cast in a role already occupied by Brad Dourif; in the final film, the actors alternate. A similar fate befell Paul Schrader’s “Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist,” which Morgan Creek was sufficiently dissatisfied with to shelve and supplant with an entirely different prequel, the film that became “Exorcist: The Beginning,” directed not by Schrader but by Renny Harlin. For those interested in the vagaries of modern Hollywood, as well as the power of editing to make or break a movie, the multiple versions of “Exorcist II,” “The Exorcist III,” and the “Exorcist” prequels all exist on DVD and Blu-ray.

The “mystery of faith” may confound humanity for the rest of time, but this book proves that the mystery of good (and bad) moviemaking is almost as intractable.

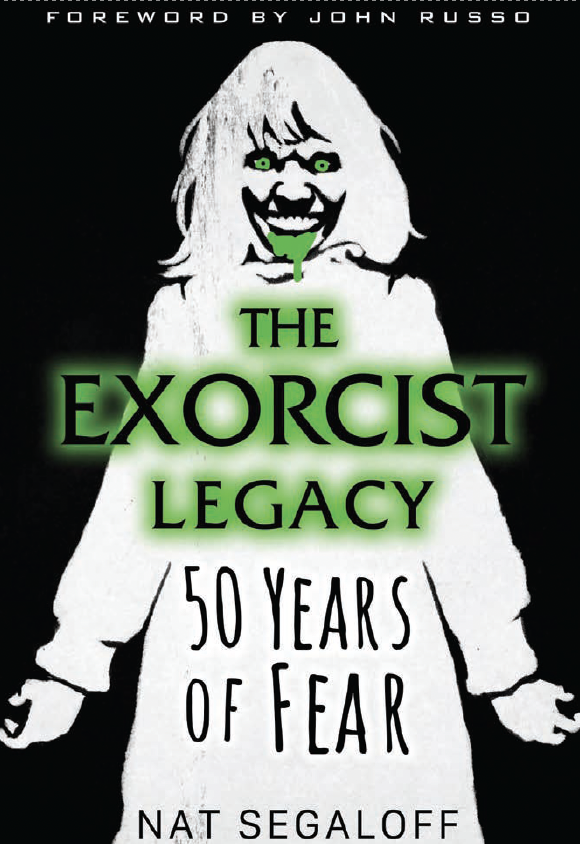

“The Exorcist Legacy: 50 Years of Fear”

By Nat Segaloff

311 pages, Citadel, $28, 2023