By Peter Tonguette

In life and on screen, picture editor Arthur Schmidt, ACE, got around. In the course of working on several of the most ambitious and accomplished contemporary American movies, Schmidt ventured into the past (and into the future), rubbed shoulders with presidents, and made contact with aliens. For director Robert Zemeckis, Schmidt was the editor of, among other classic films, the “Back to the Future” trilogy (1985, 1989, 1990), “Forrest Gump” (1994), and “Contact” (1997). He won two Oscars during his multi-decade partnership with Zemeckis: for “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” (1988) and for “Forrest Gump.”

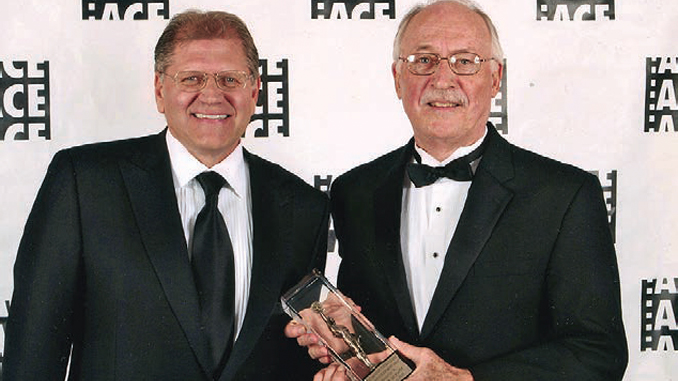

In an interview with CineMontage, Zemeckis described Schmidt as “truly a collaborator in the editing room.” “I really miss him; I really miss working with him,” Zemeckis said. “We had a great, great relationship.”

Schmidt, who died on Aug. 5 at the age of 86, was almost as well-traveled in his own life. Though he was born and raised in southern California, Schmidt spent several formative years in Spain, and throughout his life, he enjoyed journeys to new and familiar places. He was a cosmopolitan man who never let go of his early ambition to be a writer. He not only was a compulsive reader but believed all of the arts — not just the cinematic ones — ought to inform his work.

“I have a whole file of Artie’s thoughts about editing, which he prepared before giving talks,” said his wife, Susan Schmidt. “One thing he always told people is don’t get stuck behind a reel of film. Go out — go to museums, watch theater, read. It’s just as important as having the editing skills.”

Even so, Schmidt’s career path was undoubtedly lighted by his father, legendary editor Arthur P. Schmidt, who, during a long career in the industry, rose through the ranks to become the favorite editor of Billy Wilder, whose films “Sunset Boulevard” (1950), “Sabrina” (1954), and “Some Like It Hot” (1959), among others, he edited. One of four children born to Arthur Sr. and his wife, a former Goldwyn Girl named Madeline, Schmidt relished a childhood spent in close proximity to the business.

“From what I hear, he spent all his spare time at the movies,” Susan Schmidt said. “And, every time we saw an old movie on television and the credits came up, he said, ‘Oh, I delivered papers to him/her.’”

Yet the elder Schmidt counseled his son against entering a profession with such uncertainty and stress. “His father always said, ‘Don’t go into this. Why don’t you sell insurance instead?’” Susan Schmidt said.

Upon receiving a degree in English from Santa Clara University in 1959, Schmidt did not take his father’s advice, but he also stayed far away from motion pictures. He joked he would like to be the next Hemingway. Eventually, he found work teaching English as a second language in Spain, where he met future wife Susan (whose family, though British, had long made their home in Italy).

Schmidt was finally compelled to make his way back to California after his father’s untimely death in 1965. “Two of his father’s assistants asked if he wanted a job, and he got an entry-level job in TV receiving — schlepping the uncut dailies as it was coming in after it had been shot,” Susan Schmidt said. He used to sneak into the projection booth to view the incoming material.

Years as an apprentice editor were followed by years as an assistant editor. Eventually, though, Schmidt began getting opportunities to edit, including as the assistant editor working alongside picture editor Jim Clark on John Schlesinger’s hugely successful thriller “Marathon Man” (1976), starring Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier. His own initial solo picture editing credits included Michael Mann’s made-for-television picture “The Jericho Mile” (1979), for which he received an Emmy, and Michael Apted’s biopic of Loretta Lynn, “Coal Miner’s Daughter” (1980), for which he received his first Oscar nomination.

It was on another picture directed by Apted — the 1984 drama “Firstborn” — when Schmidt first crossed paths with Zemeckis. The director was casting about for young actors who might be considered for the role of Marty McFly in “Back to the Future,” a process that took him into Schmidt’s cutting room on “Firstborn.” Although Zemeckis did not find the right actor in the footage, he admired how the scenes he screened were edited.

“Back to the Future,” which Schmidt co-edited with Harry Keramidas, ACE, inaugurated what became one of the most noted editor-director collaborations in Hollywood. “That’s where it became very obvious that we were a really good fit,” Zemeckis said. “Cinematically, he finishes my sentences.”

Zemeckis said that, as his films became more and more accomplished, the process of editing was less and less about cutting around problems than making the film sing. “[Artie] comes in and you’re watching his cut and you go: ‘Yup, he cut to that reaction in the perfect place. You know what — that’s better than I ever could have imagined,’” Zemeckis said. “That’s the real collaboration.”

Zemeckis singles out Schmidt for praise on “Roger Rabbit,” which melded together live-action and animated footage in what was then a groundbreaking fashion. “We were literally editing different color leader, just cutting different color leader together with dialogue track, to start to form the movie,” Zemeckis said. “Every time some animation would come in, everything had to be re-edited.”

In a profile in CineMontage, Schmidt recalled the precision required to cut in animated footage which had cost a fortune to produce. “It was almost like cutting negative,” Schmidt recalled. “I asked if I could have an extra eight frames on every shot, just in case. ‘They said, ‘Absolutely not!’”

Zemeckis said of Schmidt’s work on the film: “If there was ever someone who deserved an Academy Award, it was Artie for that movie, 100 percent.”

Their work continued on a slate of ambitious, eclectic, and challenging films, including “Death Becomes Her” (1992), “What Lies Beneath” (2000), and “Cast Away” (2000). “He could find the perfect moments, the perfect parts of a performance, even when the actor wasn’t doing anything,” Zemeckis said. “He never left anything great on the editing room floor — he found it all.” After the last two films, Schmidt began the process of stepping away from the business, though Zemeckis lured him back into his cutting room on the 2012 drama “Flight” — the director’s first live-action film in a number of years.

“I had Artie come in a little bit just to make sure we weren’t going down the wrong road with anything,” Zemeckis said. “I’d been doing the digital movies.”

Schmidt’s own passion music meant that he particularly enjoyed placing temp music on his cuts. “He had a fantastic knack for just knowing the right piece of temp music to put in,” Zemeckis said. “You would go, ‘Oh yeah, it’s going to work so much better now.’ . . . It was really like having that second brain — or second heart, maybe.”

In addition to his wife, Schmidt is survived by his brothers, Ron and Gregory.