by Rob Callahan

Picture a box. Make it nondescript, unadorned. Its only remarkable feature is a slot cut into its top. Imagine that this box has one sole purpose: It exists so that you, and others, might write what you would like on pieces of paper, and then deposit those pieces of paper in the slot.

Now decide: Do you want it to be a suggestion box or a ballot box?

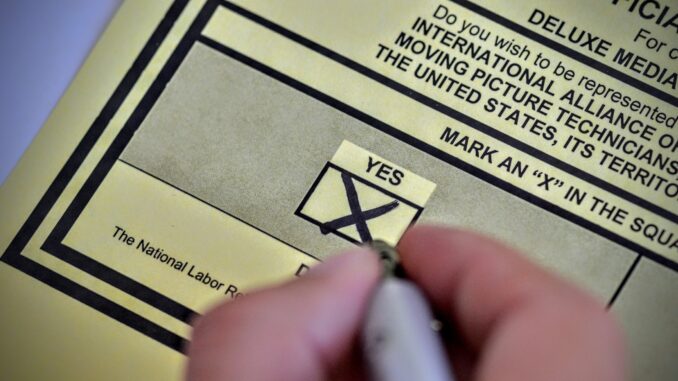

In early October of this year, a group of employees at Leftfield Entertainment, a large reality television production company in New York, faced such a choice, set more or less explicitly in just such terms. And, only a few weeks earlier, the employees of Deluxe Culver City, an LA-area post-production facility, made effectively the same choice themselves, albeit not as explicitly framed. Both of these choices took place in the context of union certification elections conducted by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

The Leftfield employees were writer/producers who had petitioned the NLRB to conduct an election in which they could certify the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) as their union. Not long after they filed their petition with the Board, their management e-mailed a rambling, anti-union screed to the writer/producers on company staff. Within the jumble of the e-mail’s assorted arguments and aspersions was a curious reminder: Management wanted to call everyone’s attention to the fact that the company had recently installed a suggestion box.

The message implied that elections and negotiations were rendered extraneous by the elegant simplicity of a box into which employees could easily deposit notes to their bosses. What need for the ponderous mechanics of collective bargaining when there’s already a mechanism for the submission of one’s ideas to management’s thoughtful consideration?

If employees choose the ballot box, they insist upon both a voice and a vote in decisions shaping their working lives.

Like this production company, almost every non-union employer runs an anti-union campaign when it discovers that its employees intend to organize. Virtually all such campaigns include boasts of the employer’s “open door policy,” inviting employees to discuss their concerns directly and individually with management — without the intrusive intervention of outsiders from the union.

Indeed, Deluxe Culver City made a substantively similar argument to members of its staff when they sought to organize. In one of the company’s anti-union e-mails to the facility’s employees, it wrote, “We pride ourselves in having a direct relationship with our employees and believe this is central to our success as a company. Having a union or third-party bargaining agent…would change the partnership we have with our employees.”

Every employer fighting unionization makes the case that employees’ interests are best served when they discuss their concerns with the employer individually and directly, through the “open door.” The claim in this one e-mail from the production company was really no different. Only, in this instance, the “open door” had narrowed to the width of a slot.

Unwittingly, perhaps, Leftfield’s e-mail laid out a useful set of metonyms to illustrate the decision before the employees — the same decision facing all non-union employees contemplating collective bargaining. Do they opt for the suggestion box or for the ballot box?

If employees accept the suggestion box as their ultimate means of participating in workplace decision-making, they effectively relegate themselves to the role of supplicants, empowered only to recommend changes to the terms of their employment. Perhaps management will honestly consider the ideas submitted to them, or perhaps they will ignore all proposals, thus rendering the suggestion box no more effective than a wishing well. In either scenario, though, the separation of roles is clear: Employees suggest; management decides.

If, on the other hand, employees choose the ballot box, they assert their right to democracy on the job, insisting upon both a voice and a vote in decisions shaping their working lives.

Deluxe Culver City employees chose Editors Guild representation with a Union Yes vote of 92% in early September.

Democratic participation in decision-making is perhaps the most fundamental distinction between organized and non-union workplaces. When I talk to post-production employees about the advantages of working union jobs, most often I hear them express interest in the contractual terms one can readily quantify. Folks speak of higher wages, excellent health and retirement benefits, better hours and the like. Less often does anybody mention enfranchisement as one of the perks of union employment.

But workplace democracy is, in fact, the wellspring from which all the other advantages of union employment flow. The superior conditions secured through union contracts don’t originate in employers’ largesse, nor can our union negotiators, however skilled, conjure them from nothing. They come from the difference in clout between those employees who can only entreat employers for improvements on the job, and those employees empowered to elect the terms under which they will sell their services.

Witness the recent contract negotiations between the United Auto Workers (UAW) and Fiat Chrysler, in which the employer substantially improved its offer after UAW members voted down a tentative agreement that the employees felt did not go far enough to remedy a despised two-tier wage system. Employers who know their offers must pass the test of a popular vote calculate their employees’ worth differently than employers who are free to simply make take-it-or-leave-it offers to individual workers.

Winston Churchill famously popularized the apothegm, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried.” And it is true that the ballot box is no panacea. The democratic process is more often ugly than utopian. In the workplace as well as in the civic sphere, the practice of democracy gets muddled in imperfections, affording no guarantees of easy progress. Even enfranchised employees often struggle to convince management to take their concerns seriously. Moreover, majority rule only translates into real bargaining power when coupled with a commitment to solidarity.

But nearly 90 percent of employees in the United States now work in jobs without any meaningful mechanisms for democratic participation in decision-making. If democracy’s merits are remarkable chiefly in relation to all the other forms of governance that have been tried, it’s noteworthy that democracy has only seldom been assayed in the workplace. On the job, dictatorship — sometimes benevolent dictatorship and sometimes not — is the default mode of governance. With the steady decline of union density in this country, fewer and fewer employees are empowered to vote on the terms of their jobs. It’s no coincidence that in the past several decades that workplace democracy has been on the wane, our country has experienced wage stagnation and exacerbated inequality.

Thankfully, employees are still able to come together and insist upon their right to democratic collective bargaining. Organizing isn’t easy, and the campaigns employers wage to discourage it can be both aggressive and effective. But that doesn’t mean that groups of workers are unable to successfully challenge management’s dictatorship in the workplace.

In both of the union certification elections I have touched upon here — the WGAE’s October election at Leftfield and our September election at Deluxe Culver City — employees soundly rejected the suggestion that they be satisfied with a suggestion box. They elected instead to have a voice and a vote on the job. The writer-producers in New York chose WGAE representation with a Union Yes vote of 64% in early October; the post-production professionals in California chose Editors Guild representation with a Union Yes vote of 92% in early September.

Each of those groups, like every group of employees who elect union representation through the NLRB’s certification process, now faces contract negotiations with its employer. The margins of the votes notwithstanding, there’s no guarantee that either set of negotiations will be easy or even amicable. Employees have voted themselves a seat at the bargaining table, but there is no assurance that they will come away from that table with everything they seek.

What is certain is that they now have a meaningful means of participating in decisions that used to be the sole prerogative of their bosses. That’s democracy at work. Imperfect, perhaps, but far superior to its lack.

If you are working a non-union job in post-production, and you are interested in having a voice and a vote in your workplace, talk to an Editors Guild organizer. You can call the Guild’s organizing hotline at 818-925-6734 or contact an organizer through our organizing website, www.PostProud.org.