by Edward Landler • photos by Peter Zakhary/Tilt Photo

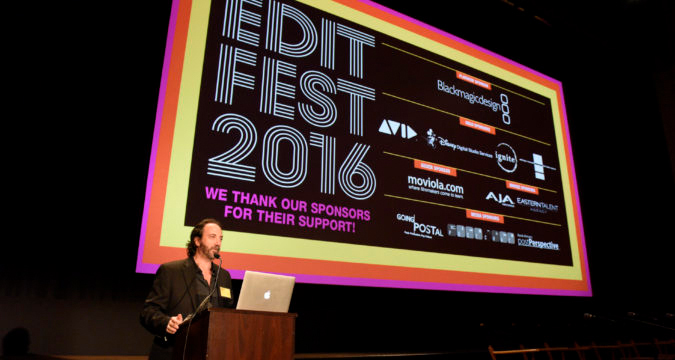

On an early August Saturday, a capacity crowd of established and aspiring post-production personnel filled the Main Theatre of the Disney Studios in Burbank for EditFest LA 2016, organized by the American Cinema Editors (ACE). A day-long celebration of the art and craft of editing, the event’s ninth annual presentation offered four panels of film and television editors sharing their insights and experiences.

Editor (and Professor of the Michael Kahn Endowed Chair in Editing at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts) Norman Hollyn, ACE, noted, “EditFest is awesome because it’s a bunch of editors talking about editing and a bunch of people interested in editing talking about editing.” In the theatre, the audience indicated by a show of hands that almost half were editors, and almost as many were assistant editors.

Welcoming the audience, ACE Vice President (and President as of August 16) Stephen Rivkin, ACE, thanked event platinum sponsor Blackmagic Design and other sponsors, including AVID, the Motion Picture Editors Guild and event host Disney Digital Studio Services, as well as ACE Executive Director Jenni McCormick and her staff. Following is a re-cap of the panels:

Cutting It in Hollywood

John Axelrad, ACE (Crazy Heart, Rudderless)

Zene Baker, ACE (Neighbors, This Is the End)

Barbara Gerard (Brothers and Sisters, Supergirl)

David Rogers, ACE (The Office, The Mindy Project)

Moderated by Mitchell Danton, ACE (Survivor, Switched at Birth)

The day’s first panel was inspired by moderator Danton’s recent book, Cutting It in Hollywood: Top Film Editors Share Their Journeys. For the book, the author interviewed 23 editors to explore their personal learning experiences and what they faced to achieve their aspirations in the industry.

Four of the editors joined the moderator to share their insights with the EditFest LA audience. “The best storytellers make the best editors,” said Danton, and he asked them how they got their first big breaks into the business.

“For most of us, it’s a series of small breaks,” said Axelrad. Who is also an MPEG Board member. After USC Film School, he honed his skills on the Avid and started amassing contacts while gaining editing credits on low-budget and deferred payment projects. Eventually, he found work as an assistant with top editors, including Anne V. Coates on Out of Sight (1998) and Erin Brockovich (2000). For the last 15 years, he has been editing major features.

That same constant drive to build on incremental breaks characterized the other panelists’ early progress. Baker made corporate videos in Raleigh, North Carolina until ex-film school classmate David Gordon Greene asked him to edit what became an acclaimed indie, George Washington (2000). Coming to Los Angeles, Baker’s regional background sidetracked him until the director of another indie film he had edited brought him in to edit his first studio project. The star of that project was Seth Rogen, who has regularly called on Baker to edit the pictures he produces, starting with 50/50 (2011).

From an animation house in the Bay Area, Gerard made the move to LA and got into the Guild as an assistant editor on a slasher movie. An assistant on Fox’s The Pretender (1996-2000), she was allowed to cut scenes and later to edit full time. It was much harder getting her second series, the later seasons of Dawson’s Creek (1998-2003), but she said, “Executive producer Greg Berlanti has kept me employed ever since on seven shows.”

When Rogers came to LA, he worked in a post house as a runner and spread his resume reels all over town hoping to get a post-production assistant job. From assistant editor at a trailer house, he moved on to being assistant editor on the last three seasons of Seinfeld (1989-98). Then he edited a string of TV series, which led to editing, directing and producing The Office (2005-13) and The Mindy Project (2012-present).

For the rest of the session, Danton asked the panelists to screen sequences from their work, which presented a major problem from which they had learned. For Axelrad, it was a leaden-paced scene with too much dialogue from James Gray’s Two Lovers (2008), in which Joaquin Phoenix takes ex-girlfriend Gyneth Paltrow to the hospital — with no budget for reshoots.

“To get more sympathy, we used ADR to change the dialogue,” he said. “We cut the entire conversation in the waiting room and cut straight to the hospital room. Instead of drug abuse, she was there because of a miscarriage. Then in the cab going home, no dialogue, just two people holding each other; silence was more powerful… Editing is the best rewrite.”

Baker spent two weeks editing a loud frat party in Neighbors (2014), in which neighbor Seth Rogen coordinates a plan to get a frat guy to see his girlfriend hooking up with a fraternity brother. The editor said, “The original was much longer; it all had to get condensed, but the audience had to constantly connect who was being talked about.”

When Rogers came to LA, he worked in a post house as a runner and spread his resume reels all over town hoping to get a post-production assistant job. From assistant editor at a trailer house, he moved on to being assistant editor on the last three seasons of Seinfeld (1989-98). Then he edited a string of TV series, which led to editing, directing and producing The Office (2005-13) and The Mindy Project (2012-present).

To keep it moving, Baker used the music to link the action but had to retime practically all the shots. Fortunately, they shot the scene at a super-low frame rate to allow them to ramp up the speed of shots.

Like the other clips, Gerard’s scene from TV’s Supergirl (2015-present) with over 250 visual effects was originally much longer. An entire fight up in the sky over Metropolis had to be cut to allow a 45-second shot — in which Supergirl apologizes for the destruction she caused after exposure to red kryptonite — to remain. Gerard said, “The studio objected to it, but our creative personnel pushed back to keep the whole apology.”

Rogers finished the session with two sequences that he both directed and edited from The Office and The Mindy Project. He said, “It’s fun and rewarding to do both, but extremely challenging.” The Mindy scene depicted a baby’s head being shaved but the baby cried whenever the electric razor came near. Rogers said, “We shot and edited so that no one noticed that we didn’t show the shaving; the audience just assumed it happened. The smoothest editing lock process ever and the studio producers approved immediately.”

Cult Film Favorites

Mark Goldblatt, ACE (The Terminator, Armageddon)

Mark Helfrich, ACE (Showgirls, Rush Hour)

Tina Hirsch, ACE (Death Race 2000, Gremlins)

Norman Hollyn, ACE (Heathers, Wild Palms)

Jane Kurson, ACE (Beetlejuice, Monster)

Moderated by Michael Krulik, Avid Principal Applications Specialists

With four editors discussing the cult films they worked on, moderator Krulik asked them what made them cult films.

Hirsch described Death Race 2000 (1975) as “weird, wacky and kind of low budget.” Helfrich saw Showgirls’ cult status “as a guilty pleasure.” What makes The Terminator (1984) a cult movie, said Goldblatt, “was that no one had any expectation for it and it hit a chord.” Hollyn said Heathers (1988) is a cult movie “because everyone working on it really cared about the movie and not what other people said.” Kurson, the only one on the panel who never worked for Roger Corman, said of Beetlejuice (1988), “It’s not like any other film; it’s its own category.”

Before screening a scene from James Cameron’s The Terminator, Goldblatt thanked Hirsch: “Tina, Death Race 2000 got me off my butt to go over to Corman and get a job as an editor.” That’s where Goldblatt met Cameron. About the clip showing Arnold Schwarzenegger’s cyborg hunting Linda Hamilton, he said, “This is tech noir… You’ll see how points of view work in the sequence.” The film took 10 weeks to edit and, he said, “The material was such that you just have to be focused and it kind of cuts itself.”

When Helfrich learned that Showgirls (1995) would be reated NC-17, he wanted to edit it. He said, “Without doubt, the most fun I’ve ever had on a film. We edited in a working Tahoe casino with naked showgirls walking in and out of the editing room.” It was later noted that it was the only clip from a “naked” movie ever screened at Disney Studios. The sequence’s dance number prompted Krulik to point out Helfrich’s work on music videos. The editor said that the movie turned out the way it did because of director Paul Verhoeven: “He had final cut.”

Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000, produced by Corman, cost only $300,000. Hirsch said, “We started working on it in February and it opened April 29, but it wasn’t about the money, it was about working with Paul.” The film’s beginning was screened with the editor referring to the producer’s control, “We hoped this would be a seven-minute sequence, but it had to be five.”

Hirsch never went to film school; she learned by doing. She said, “On low-budgets, early on I learned I had to work with what I had. On higher-budget shows, they were surprised I never asked for reshoots. Walter Hill hired me because he saw Death Race; he said, ‘If you can cut that sh*t, you can do anything.’”

When Hollyn read the script for Heathers, the material excited him. In the film’s opening sequence, he said, “We were juggling tone and juggling plot information, sort of inventing our own language… If you’re not with us through this, you’re not with us through the rest of the picture.”

While eventually achieving cult status, Heathers’ initial cut was changed. Originally, Winona Ryder and Christian Slater both get blown up and go to the high school prom in heaven. Hollyn recalled, “The distributor told us, ‘We’re not giving you $3 million to blow up our hero.’” As it turned out, the distributor went out of business shortly before the film opened.

Hirsch never went to film school; she learned by doing. She said, “On low-budgets, early on I learned I had to work with what I had. On higher-budget shows, they were surprised I never asked for reshoots. Walter Hill hired me because he saw Death Race; he said, ‘If you can cut that sh*t, you can do anything.’”

Kurson worked on Beetlejuice for a year. She cut to the script, in which Michael Keaton’s demon Beetlejuice only appeared in three scenes; she felt the audience would feel cheated. She said, “David Geffen gave us more money to shoot new scenes and that made it a good movie.” After screening the scene introducing the demon, she told of how director Tim Burton would watch scenes in the editing room and make weird noises: “He was doing the sound effects to the scene… You shouldn’t take things personally when you edit.”

Wrapping up, moderator Krulik asked the editors what their favorite cult movies were. For Goldblatt, it was Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970); Helfrich picked Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970). Anything by Stanley Kubrick was Hollyn’s choice and Kurson said, “Anything by [Luis] Buñuel.”

Hirsch chose her own film, Xanadu (1980): “While working on it, I had a dream. I’m on the lot with the movie’s main editor, and stars come up in the sky in the shape of a heart. I told people the dream at work and producer Joel Silver made it the real beginning of the movie.”

Inside the Cutting Room: A Conversation with…

Michael Tronick, ACE (Straight Outta Compton, Hairspray)

Moderated by Bobbie O’Steen (author of The Invisible Cut and Cut to the Chase)

Introducing Tronick, O’Steen brought attention to his career as a music editor before her turned to picture editing, and asked about the mentors who helped guide his career. Praising music editor Dan Carlin, Sr., composer Ralph Burns, picture editors John Wright, ACE, Billy Weber and Chris Lebenzon, ACE, Tronick told of how he “tried to extract abilities and qualities from these people I worked with.”

Their influence in shaping his career soon became more apparent. A political science major in college, Tronick was attracted to the teamwork he found working on student film projects. Later, working with an industrial film production company where Carlin was on staff, he gravitated toward post-production and became the music editor’s “schlep” for Carlin’s feature film work.

Becoming a full-fledged music editor on Semi-Tough (1977), he worked on Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (1979) and Star 80 (1983) with Burns, and screened a clip from Jazz. Fosse and the composer, Tronick said, “taught me how to really listen… and Fosse was the kind of director who got out of me what I wasn’t aware I had in me.”

Recounting tales of Dede Allen, ACE, running post-production “like George Patton” on Reds (1981), and Mick Jagger and Hal Ashby on the concert film Let’s Spend the Night Together (1982), he moved on to his transition to picture editing. Working with Wright on Outrageous Fortune (1987) led to editing picture for musical sequences on a TV feature Wright was cutting.

Then, he joined Lebenzon and Weber as third picture editor on Beverly Hills Cop II (1987), the project that made him a full-time film editor. He said, “I was in awe of my colleagues. At the end of the day, my trim bins — remember those — were overflowing and Billy just had a couple of clips. I was so embarrassed, I’d stay late to clean out my bins.”

Introducing the tango sequence with Al Pacino and Gabrielle Anwar from Scent of a Woman (1992), Tronick voiced his respect for director Martin Brest: “Marty maintained the sanctity of the editing room until he finished his director’s cut.” After viewing the blind man dancing with the young woman, O’Steen noted, “You start with her joy rising and then you cut to Pacino’s buildup of joy.” Tronick answered, “As a music editor and a musician, you develop an innate sense of rhythm, and then this camera crew gave me all these choices…over 100,000 feet were shot for the tango sequence.”

To edit the next clip, the cat-and-mouse shootout between Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt in Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005), Tronick insisted the footage be junked and reshot in a “decent house” to make it the “kick-ass scene” they wanted. He said, “I don’t like going to a set, but that time it was invaluable for me to see what the layout was.”

Recounting tales of Dede Allen, ACE, running post-production “like George Patton” on Reds (1981), and Mick Jagger and Hal Ashby on the concert film Let’s Spend the Night Together (1982), Tronick moved on to his transition to picture editing.

This was followed by another dance sequence, from Adam Shankman’s Hairspray (2007), with Christopher Walken and John Travolta as Wilbur and Edna Turnblad dancing in their yard. Shankman, who also choreographed, “would dance in the cutting room to show me what moves to cut to,” the editor said.

The conversation concluded with a clip and a discussion of Tronick’s most recent work, Straight Outta Compton (2015). Cutting it with director F. Gary Gray and editor Billy Fox, ACE, he said, “I wanted to make the movie accessible to me and to audiences. I realized the impact of the NWA album, at the level of a Sgt. Pepper; I gained a respect for their musicality and the whole art form.”

The Lean Forward Moment

Jeffrey Ford, ACE (Captain America: Civil War, The Avengers)

Kim Roberts, ACE (The Hunting Ground, Waiting for Superman)

Kevin Tent, ACE (The Descendants, Nebraska)

Susan Vaill, (Grandfathered, Grey’s Anatomy)

Moderated by Norman Hollyn, ACE

For the day’s final panel, the group members discussed scenes they did not edit but that inspired them to edit. Best known for his recent work on superhero movies, Ford presented a scene near the climax of Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff (1983), edited by a team of five editors. Ford said, “We carry the rhythm and grammar of these works into our own work. You steal from it and you’re inspired by it.”

The sequence inter-cuts jet pilot Chuck Yeager on a test flight with a gala celebration for the Mercury 7 astronauts just before the first manned space flight. Ford extolled its “movement, sound and music. It is utterly defiant about how you wait for things. It’s becoming harder to do this kind of thing today — the cross between total art cinema and total entertainment.”

Moderator Hollyn brought up the issue of cutting for style’s sake vs. emotional punch. Action editor Ford felt that character or narrative determined his cutting, not just style. With her background on TV series, Vaill said, “I investigate style for the need of innovation; the innovation demands I cut for style, but mostly it’s for performance and story.”

Jumping between big issue and personal documentaries, Roberts said, “Sometimes style comes from negotiating with what you have and sometimes the director comes in with a sense of style.” Tent, best known for working regularly with writer/director Alexander Payne, responded, “In all of the films I’ve worked on, the style just happens organically; it’s not something consciously that I do.”

The last clip, presented by Vaill, was the climactic 100-meter race from Hugh Hudson’s Chariots of Fire (1981), edited by Terry Rawlings, ACE. The TV editor said, “I saw this when I was 11 and I became a sprinter.”

Roberts screened a clip from Terry Zwigoff’s documentary Crumb (1994), edited by Victor Livingston, that starts to set up the relationship between cartoonist Robert Crumb and his brother Charles. She said, “It encompasses a lot of what I like about documentary. You pick up all the details that have nothing to do with what they’re saying; they let the viewer discover things. It does a lot of work that pays off later.”

Unlike the Ken Burns “photo, photo, photo” style, said Vaill, “The character actually shows you his comic book covers in the moment.” The moderator asked how the audience understands what the filmmaker wants, and Tent said, “Hopefully, your editing will show them what you’re thinking. You want to show it slowly…they get engaged.”

Tent went on to screen EditFest’s second clip from All That Jazz, edited by Editors Guild President Alan Heim, ACE. Beginning with the Fosse-like main character’s fantasy conversation with death, the sequence takes him to a film cutting room (“Alan cut it and he’s in it,” noted Hollyn) and a theatre rehearsal. Tent said, “It feels very free; they cut where they want it to.”

The musical nature of the movie led to a discussion of how the panelists work with music. Tent said, “Music helps me get used to the cuts.” Roberts responded, “I often get stuff with zero style. Music helps me build to the style, but it’s also a crutch.” Ford never listens to a film’s music while editing but will listen to other music while cutting — “but not if it’s synchronous.”

The last clip, presented by Vaill, was the climactic 100-meter race from Hugh Hudson’s Chariots of Fire (1981), edited by Terry Rawlings, ACE. The TV editor said, “I saw this when I was 11 and I became a sprinter. I love the bizarre rhythms: Two minutes go on before the gun; the race is 10 seconds and it’s over in a flash, and they keep reliving and reliving it.” Tying it all together is the emotional tableau of the coach, played by Ian Holm, alone in a room with a bird in a cage.” Vaill sums it up, “I love how it plays with time — the delayed gratification of it.”

To conclude the session, Hollyn relayed questions via Twitter from the audience to the panel, such as, “What’s your favorite way to drive narrative?” Vaill answered, “Sometimes by cutting off the beginning and the end of the scene, so you’re left with the problem of what the scene itself is.” Tent approved, adding, “So you’re conscious of the last thing that audience members think about when they move from the last scene to the next one.”

And, finally: “What rules have you broken and why?” Ford said, “The worst thing you can do is conform to a film school dictum.” Tent continued: “I don’t think there should be rules; do whatever you need to do and can do to make it work.” Roberts finished with, “One of our biggest tools is surprise — and not following a rule is a surprise.”

With that, the audience and the panelists went outside for the EditFest after party to eat, drink and carry on…talking about editing.