by Norman B. Schwartz

One morning back in 1976, when I had offices in the old Samuel Goldwyn Studios in the heart of Hollywood, I received a call from the head of sound services who knew me well because I was then the president of a very successful post-production company that specialized in dialogue sound editing, voice casting and dialogue direction. Seemingly, that morning an English technician who was supposed to have watched over lip-sync during an ADR recording session had not yet shown up and the director and actor had been kept waiting for an hour in a sound studio, unable to re-do dialogue scenes from their movie. My colleague asked if I would cover the session.

The first thing I asked was the name of the film and the actor. “Superman: The Movie, with Marlon Brando,” was the answer. The film, which had not yet been released, was already famous because an actor had asked for and received the most money for the least amount of days worked in the history of motion pictures: $3.7 million and a percentage of the profit––for 12 shooting days.

“After the first take, he looked over at me at my table with penetrating eyes that said, ‘You know and I know that what I am doing is crap––but that’s all you’re going to get. Take it or leave it.’ I pointed out the words and phrases that were out of sync, and suggested he go for another take.” – Norman B. Schwartz

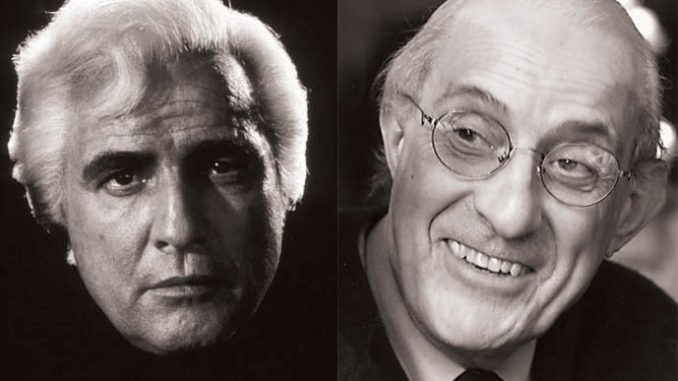

As I crossed the studio lot to the ADR recording stage, I envisioned the Brando most of us remembered from his unforgettable first films: the pouting, sexy, terrifying but mesmerizingly handsome hero of A Streetcar Named Desire, and the surly head of the motorcycle gang in The Wild One (“What am I rebelling against? What have you got?”). These performances had revolutionized film acting; they seemed so real that any actor who followed after them could not have helped imitate him in some fashion.

When I entered the studio, what I found instead was not that beautiful, young man of memory, but an enormous whale of a man—he then weighed about 220 pounds. The creature had stuffed himself into a chair and was very angry for having been kept waiting. When I introduced myself, explaining that I was subbing for someone else, he looked me up and down, inside in and out, with a look that said: “You better know what you’re doing, kid, be-cause if you don’t––I’m walking.”

The director of the film was seated on the sofa in the back of the studio reading a trade paper and seemed totally uninvolved. I had no other recourse but to go to work…or pretend to…

Although I had never seen the film, I looked at the sheets of dialogue someone in England had prepared. Instead of being broken down into short sentences––which would have been easier for the actor to synchronize––there were long, florid, Shakespearean speeches that went on and on. Rather than to explain how difficult perfect synchronization was going to be, I pretended all was in order.

Brando’s first, long speeches as Jor-El, father of Superman, were projected on the screen so that he could study the original noisy soundtrack. He watched and listened to his expensive performance without the slightest interest, managed to push himself up from the chair, wobbled to the microphone, put on earphones and began re-recording the dialogue under these ideal conditions. I immediately noticed that he was making no attempt at anything that resembled a true performance; his voice was monotone, his lip-syncing questionable at best.

© Warner Bros.

After the first take, he looked over at me at my table with penetrating eyes that said, “You know and I know that what I am doing is crap––but that’s all you’re going to get. Take it or leave it.” I pointed out the words and phrases that were out of sync, and suggested he go for another take. Despite his apparent insouciance, he was still clever enough––or perhaps still professional enough––to catch most of the lip-sync errors. After a few takes, I knew that with a lot of cutting and pasting from one take to the other, all of it could be made to fit.

We went on like this mechanically, line after line, cue after cue, for a while until Marlon suddenly stopped, turned to the glass window of the control booth and asked in a loud voice if it was possible to get some water. Instantly, the sound system in the stage clicked on and an amplified voice in the dark replied, “What sort of water, Mr. Brando?”

“Perrier.”

To this day, I don’t know how the task was accomplished so rapidly, but by the time we finished the next take, a six-pack of green glass bottles was on the table before him. Brando opened one with his huge mitt of a hand, and began drinking from the mini-bottle. Suddenly he stopped, got up slowly from his chair, walked over to the table where I was keeping notes and, in a new and totally unrecognizable voice, asked, “Would you like one, Norm?”

I nodded, unable to speak. The monster with the six-pack was smiling down at me––a smile of infinite sweetness that every person who has ever worked with a movie star recognizes. It means: “I like you. You know what you’re doing.” Before my eyes, the creature had transformed himself into an eight-year-old asking me to be his friend. Such is the way of actors.

We continued working. The tonality of the voice never changed, but after two or three takes, it would usually synchronize more or less to the face in front of us on the screen. By the end of the morning, we had finished re-recording the last line of dialogue to be replaced.

“How was it, Norm?” he asked.

“Fine, Marlon,” I said. “I’m sure they’ll be able to get it all in sync.” Who they were I didn’t know or care.

“No,” he said, “ I mean how was it over all?”

Over all? He stared at me with those X-ray eyes of his, daring me to tell the truth. I could not speak it, but neither could I lie to him. I tried to suppress my inner thoughts, but I knew he could somehow hear them. “How is it possible,” I thought loudly, “That a man like you, Marlon––surely the greatest American actor of our generation––could have reduced himself to such a hack and whore?” For of all the people in the world who might have been asked that question, who was better qualified to answer it than Marlon?

I know now that if I had had the courage then to say aloud, “Over all, it’s awful, Marlon. I mean, your dialogue can be made to sync, but there is absolutely no performance whatsoever,” he would have instantly replied, “If that’s what you think, Norm, then let’s do it all over again.”

But getting a performance that day was not my job. That was the director’s. “The lip sync’s fine,” I said. The film’s director, happy to get out of the studio with something that resembled a performance in acceptable sync, nodded his approval and called it a wrap. Brando and I shook hands. He told me it had been a pleasure working with me, and hoped we would meet again under “more felicitous circumstances.” Those were his words. But we never did… As had been the case with so many people who had come his way before and would after, I had had my morning with Marlon.

(Editor’s Note: This article is © 2010 by Norman B. Schwartz, and has been excerpted, with permission, from the author’s forthcoming book, ACT NOW: A New Approach to the Old Techniques of Acting.)