by Peter Tonguette

Midway through George Cukor’s Rich and Famous (1981), there is a scene that, all by itself, encapsulates the witty banter that was the director’s signature. The heroine of the film, a celebrated writer played by Jacqueline Bisset, is in her room at the Algonquin Hotel, ostensibly to be interviewed by a young Rolling Stone journalist (Hart Bochner). Bisset orders a drink from room service, but in the next few minutes, every one but room service shows up, including her best friend (Candice Bergen), followed by her best friend’s daughter (Meg Ryan) and her boyfriend (Daniel Faraldo).

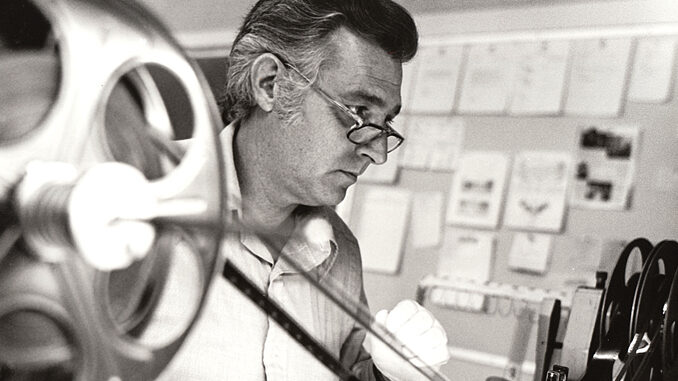

As the characters accumulate, the verbal jousting between them escalates, but it would not be half as effective without the crackerjack editing of John F. Burnett, A.C.E., collaborating with Cukor for the fourth and final time. He previously worked as an assistant on two Cukor films in the early 1960s and was nominated for an Emmy Award for editing his television movie Love Among the Ruins (1975). In Rich and Famous, each pithy one-liner is met by an appropriately terse cut by Burnett; his edits are like punctuation marks.

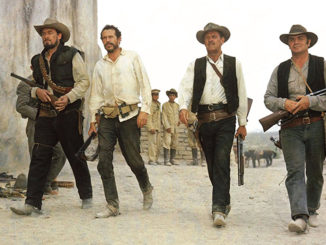

The scene, then, exemplifies both the director’s and the editor’s style. Burnett has edited every kind of film, including Westerns (1971’s Wild Rovers), romances (1973’s The Way We Were), and war epics (1983’s miniseries The Winds of War), but it is tempting to associate him most strongly with character- driven comedy-dramas like Rich and Famous. Perhaps that is why producer Ray Stark chose him to edit films in that vein, such as the beloved Neil Simon adaptations The Sunshine Boys (1975) and The Goodbye Girl (1977). He is also the earliest serving former president of the Motion Picture Editors Guild (1975-76) still living.

Burnett has a gift for finding moments of humanity beneath the lines. Running dailies with the director, he was always on the lookout for what struck him instinctually. It could be as infinitesimal as a man touching his necktie — and it is very far from a technical or rote process.

“When you’re putting something together, it isn’t like, ‘I’m in the master, now I’m going to the medium shot, then over-the-shoulders,’” Burnett explains. “Because I may run something and what do I open on? Big-head close-up. What I’m saying is, that was a certain moment that kicked that scene off for me. In The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter [1968], Cicely Tyson is having a big knockdown, drag-out with her dad. Usually, when somebody finished speaking, you cut to the other person. I must have set on her for 20 or 30 feet after she finished talking before I cut to him.”

Burnett grew up in Southern California, but despite his proximity to the movie business, his aspiration was to become a singer. He sang light opera from the ages of 13 to 17. “The problem was, that wasn’t very fashionable at the time,” he says. “I would have done much better if I was twangin’ with a guitar! The USO didn’t want to hear me sing ‘Figaro’ from The Barber of Seville!” By happenstance, after graduating from high school, it was suggested that he consider film editing as a vocation. A whole world opened up. “You may never go beyond that or you may never make editor,” he recalls being told, “but if you are an editor, there is always the door open that you may become a director or a producer. It was available.”

First, though, he had to get into the mailroom. Dressed in a dark blue double-breasted suit, he spent an entire day knocking on studio doors, meeting with no success. Before they went home, his mother (who was accompanying him) suggested they try Warner Bros., which was about two miles from the Burnetts’ house. He remembers, “I said, ‘No, Mom, it’s late, I’m tired, and I understand that Warner Bros. is the hardest studio to get a job at, and you see what kind of luck I’ve had so far!’” His mother insisted and 20 minutes later, he was the studio’s newest messenger. “Jack Warner didn’t have much of a formal education and he wasn’t that fond of college graduates,” Burnett says. “He wanted people to come through the ranks.” Burnett’s progress, however, was interrupted by a stint in the army during the Korean War, from 1952 to 1954. Upon his return, he found that many assistant editors at Warner Bros. had been pressed into service as full editors because of the new television market. His mailroom days were over.

“On a Thursday, the head of the department said, ‘You start Monday,’” Burnett remembers. “I said, ‘Well, I just got back from Korea. I’d like to have a week or two…’ ‘Come in Monday or you have no job.’”

Initially, he toiled in the coding room as an apprentice, but then something fortuitous happened: In 1955, Billy Wilder came to Warner Bros. from Paramount to direct The Spirit of St. Louis (1957), about aviator Charles Lindbergh. He was joined by his usual editor, Arthur P. Schmidt, whom, Burnett recalls, “had a very great presence. If he was walking around, you might think he was the head of the studio.” But Schmidt had to take assistants from the Warners lot. The job fell to Burnett and William Millspaugh, novices both. “They told him, ‘We’d like to give you two bright, young guys who have never done a picture,’” Burnett laughs.

After working for 18 months as an assistant on the technically challenging Spirit of St. Louis, Burnett was assigned to The Helen Morgan Story (1957). It was one in a series of classic musicals on which he was an assistant at Warner Bros., including The Music Man (1962) and My Fair Lady (1964). In working on these projects, with their immortal books and lyrics by the likes of Meredith Willson and Lerner & Loewe, Burnett’s frustrated musical ambitions proved helpful. He says, “I had to read music and put the music codes on, so when they lined up the track, everything was in sync with every take of every piece of film.”

It was not until the mid-1960s that Burnett moved up to editor, but he had been preparing for the transition. He and fellow assistant Sam O’Steen asked overworked editors in the television department at Warners if they had any sequences they didn’t have time to get to. If they did, the two would take them and work with them to improve their craft. Burnett and O’Steen also edited screen tests during this period, working one-on-one with

directors. Burnett’s first real opportunity to edit came on Blake Edwards’ The Great Race (1965), when the picture’s editor, Ralph Winters, A.C.E., was tasked — in the middle of cutting — with shooting second-unit footage.

By now, Burnett was on his way. But after his first film, an acclaimed adaptation of Carson McCullers’ The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, director Robert Ellis Miller placed him under a multi-picture contract. Eventually, Miller released Burnett so that he could begin availing himself of the many other offers coming his way. The successes began piling up, including iconic films of the early 1970s, like Herbert Ross’s The Owl and the Pussycat (1970) and Sydney Pollack’s The Way We Were.

It was at the peak of his professional success that he decided to run for president of the Editors Guild. “I had never been on the board of anything,” Burnett says. “But I had a lot of editorial stature and somebody nominated me for president.” He was reticent at first, but his wife, Rose Marie, loved the idea and suggested he write a briefletter explaining what he stood for, accompanied by a photograph of himself, to be mailed to all members. With that, the Burnett campaign commenced.

“Bernie Balmuth was running for president, too,” Burnett comments. “He asked me, ‘Hey, John, do you mind if I do a letter? We’ll put them in the same envelope and I’ll share the postage with you.’”

In 1975, Burnett succeeded Fred Chulack, A.C.E., as President of the Editors Guild. During his term, he notes, contract negotiations resulted in over a 50 percent compounded increase in wages over three-and-a-half years. On one memorable occasion in his tenure, Burnett found himself in the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, seated across from MCA Universal’s Lew Wasserman and Sid Sheinberg. “They were sitting on the bed, and sitting on the couch were the two top guys from Paramount,” Burnett recalls. He told the group that he wanted single-card, up-front credits for feature film editors. While, in 1967, Dede Allen, A.C.E., had been given such a credit on Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, it was not yet the industry standard.

Burnett recalls, “Sid Sheinberg spoke and said, ‘Lew, we can’t do that. It’s going to cost us too much money!’ And I said, ‘No, it’s not. Maybe eventually it is, stature-wise. But right now, it doesn’t cost you anything. We’re not asking for a card up-front and an extra two dollars a week. We want a card up-front to match the cameramen. We don’t want to be in the technical credits.’ Wasserman looked at me, smiled and said, ‘Sid, give it to them.’”

Even after Burnett’s time as president was over, his career highlights were not. In 1978, he enjoyed one of his biggest hits with another musical, Grease (1978), and in 1989, shared an Emmy with Peter Zinner, A.C.E., for the sequel to The Winds of War called War and Remembrance. He retired in the late 1990s, after finally producing, as well as editing, a show (Baywatch Nights) — just as he had been told might happen if he somehow got into the mailroom at Warner Bros. He never forgot the studio that gave him that unlikely first chance, or the man who ran it.

Years before, after Jack Warner had decided to sell his studio, Burnett ran into Tom Murphy, who was the assistant to Warner’s secretary, Bill Schaefer. Burnett had made editor, but had not yet had the kind of success that was to come. Even so, he told Murphy that he would like to thank Warner. Burnett told Murphy, speaking

of Warner, “Certain things happen from the top. He had a policy to give everybody a chance, whether they made it or not. Because of that, I’ve been able to give my 110 percent and do something with the opportunity.”

A few days later, Murphy called Burnett with explicit instructions: “At 2:30 tomorrow, you’re to call Jack Warner on the barbershop extension. He will be expecting your call at 2:30. Is that clear?”

“So I called him up,” Burnett remembers. “I go through this story. We must have been on the phone for 35 minutes. We finished and that was it, but he kept track of my career. I would get a call from Schaefer, saying how proud Warner was when I became president of the union and that he wanted to know what was going on with my career and if there was anything he could do to help me. And then I talked to Tommy Murphy one day and I told him what was going on. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘you became very important in his personal life.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘You know the phone conversation you had at 2:30 on Thursday? It was all being recorded. It was typed up and it’s the opening page of his lifetime scrapbook.’”

In the same way that John F. Burnett was grateful to the studio boss who called him, affectionately, “J.B.,” moviegoers should be grateful to him for all of the funny and touching human moments he found in the cutting room.