By Kristin Marguerite Doidge

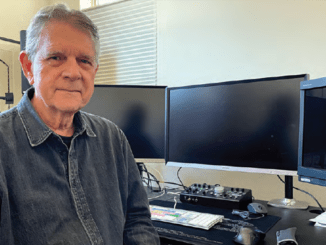

When Houston, Texas-born picture editor Mako Kamitsuna, ACE, was a little girl growing up in Hiroshima, Japan, she thought one day she might be an astronomer. But her curiosity about the unknown — about the mysteriousness of human existence — ultimately led her to the movies, instead.

“I was enamored by film itself when I was very tiny, around six or seven years old, when I first saw a Hollywood movie on a big silver screen in my hometown,” she said. “When I saw the movie, I thought, ‘If there is a profession out there when you grow up, where you could draw and you could make a living [in] moving pictures, creating pictures, this is something I could do.’”

Kamitsuna’s work as an editor was on display earlier this year in the horror comedy feature film, “Renfield,” starring Nicolas Cage as Count Dracula and Nicholas Hoult as his longtime servant. (Kamitsuna was credited as additional editor; the main picture editing team was comprised of fellow Guild members Zene Baker, Ryan Folsey, and Giancarlo Ganziano.)

“It’s a classic, iconic vampire genre film,” she said. “But what’s really interesting about ‘Renfield’ is it really keys in on the tiny insecurities of this big ego. It’s a very human flaw that this film focuses on, whether it’s Renfield or the vampire, Dracula. It humanizes these monsters in a way that is funny and painfully embarrassing at the same time, because you see yourself now in their shoes.”

She said she and her team of fellow editors approached the movie as “social commentary of the life we’re going through right now,” adding that “Dracula was like a Trumpian character.”

As for Kamitsuna’s own life and work, “Renfield” is just the latest in a long string of successes as an editor, writer, director and producer. Some of her other recent accomplishments include editing several acclaimed scripted television series for HBO, including the final episode of “Westworld” (season 2) and the first three episodes of “Perry Mason” (season 1). She also served as editor and consulting producer on the upcoming FX Network limited series reboot of “Shogun,” which will have a strong emphasis on the Japanese characters’ point of view.

“I know as editors, we pride ourselves on being ‘invisible artists,’ but what we do behind closed doors really is an essential ingredient for any material to be born as a movie,” she added. “Without our craft, the movie doesn’t exist.”

She doesn’t consider herself a career editor “per se,” but rather views writing, directing, and editing as one singular craft in the filmmaking process. “Editing is an essential craft as a filmmaker,” she said. “If you don’t know what editing is, you are depriving yourself of the real potential the movie can be.”

A ‘MYSTERY OF A STORY’

Having been “thrown” into an American school where she “couldn’t speak a word of English,” Kamitsuna found her voice as a child by drawing pictures as a manga artist. As a 12-year-old, she made her first film — an animation piece — and by the time she was a graduate film student at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, she was “indoctrinated into what film editing is.”

“I loved it,” she said. “It’s such an instinctual language for me to react to what the picture is telling you — reading visual language — and putting it together.”

Kamitsuna’s first big break in putting together a film as a professional came when she met writer-director Dee Rees in 2010. Her first task: cutting a trailer as part of a filmmaking competition to raise funds to finish what later became the critically acclaimed feature film, “Pariah.”

“She had such a rhythm and an eye,” Rees said. “Even with a trailer, she told a story.”

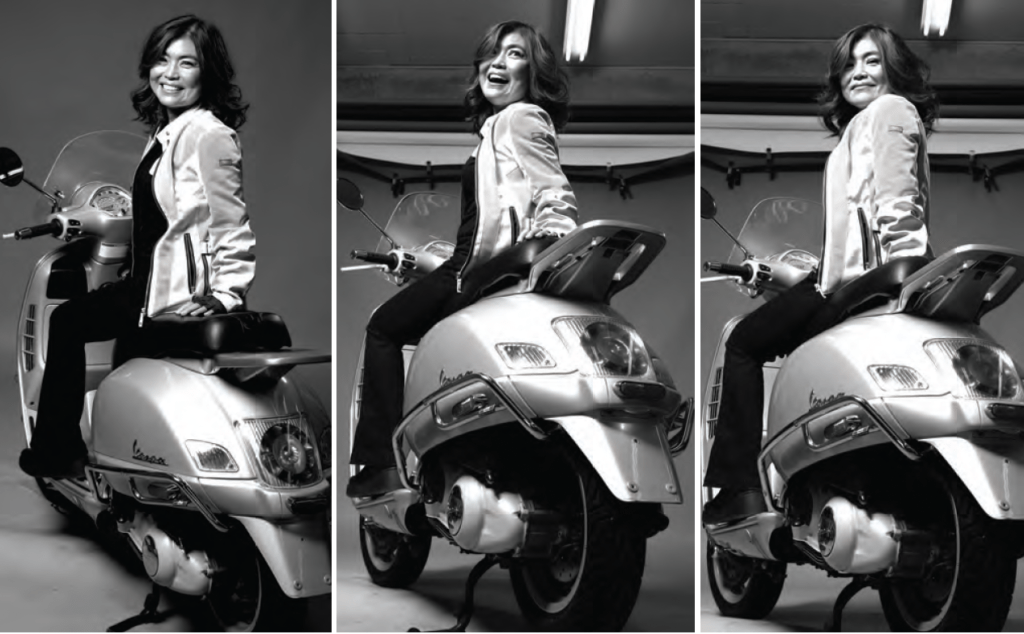

“Pariah” tells the semi-autobiographical story of a 17-year-old Black poet in Brooklyn coming to terms with her identity as a lesbian and her efforts to find acceptance from her family. Shot on a $500,000 budget over just 19 days, the film earned praise when it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2011, winning the Best Cinematography Award and the John Cassavetes Award at the Independent Spirit Awards. Kamitsuna was completely immersed in the filmmaking process, Rees said, often traveling back and forth from the set to the cutting room on her green Vespa scooter (her “spaceship,” as Kamitsuna calls it) with footage on a hard drive. When she initially recommended adding one more poem to the film, Rees balked at the idea. But Kamitsuna insisted. “She isn’t afraid to go toe to toe with a director to create something better,” Rees said. “And that idea ended up being transformative.”

In 2016, the pair rejoined forces on “Mudbound,” the Oscar-nominated feature film adapted from the novel of the same name by Hillary Jordan. The mutual trust between director and editor allowed for a shorthand — and greater experimentation — to take place.

“This is all about ‘give me your best’ — provoking each other to keep trying, keep doing,” Kamitsuna said. “It’s all about making this movie fly, transform, and transport audiences. Whatever flexibility and experiments we did, Dee always had an unwavering understanding of what this movie needs to be about.”

For Rees, she found that the moment of transformation in “Mudbound” came when Kamitsuna recommended changing the sequencing of an important scene, adding that “she’s masterful at her craft.” The film, which starred Carey Mulligan, Garrett Hedlund, Jason Clarke, Mary J. Blige and Jason Mitchell, went on to earn four Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress, Best Cinematography, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Original Song in 2017.

Having split her time as an editor between documentary, narrative features, and scripted television, Kamitsuna said she always looks for “something that is not being said.”

“I look for a moment when it crosses over regardless of language, color of your skin, or the culture — the universally resonating basic language, basic story, basic conflict. That’s what I always look for in a narrative,” she said. “All that being said, it’s really a mystery of a story. There’s always a story behind a story. Truth is hidden. Mystery is what binds it all together.” As for her nonfiction work, Kamitsuna called working with director Michael Mann on the four-part documentary series “Witness” in 2012 “world-shifting,” adding that his work ethic was “eye-opening and so impressive.”

“It’s almost superhuman,” she said. “He doesn’t stop questioning his material, pushing everybody to continue to search, look, enhance, improve, sometimes undo it and start from scratch. Just endless, endless effort. He demands a lot from people and editors, but he proves himself by doing the work himself. Having that [experience] was quite remarkable.”

While “Witness” focused on a raw look at war photojournalists in the field, her next Mann-directed project, “Blackhat,” was an action thriller about illegal hacking based on real events that took place in Iran several years earlier. The 2015 film starred Chris Hemsworth, Viola Davis, and Wei Tang, and was the first feature Mann shot entirely using digital cameras.

His commitment to authenticity and experimentation inspired Kamitsuna in the cutting room, too. “One thing Michael said to me that really freed me was, ‘you’re an artist, so play with the material. Show me what you do, show me what you feel,’” she said. “That awakened me to the responsibility of editors to show all the new potential options that the material has in store.”

As for what’s in store for the future, Kamitsuna said she’d still like to do “bigger, more challenging studio movies with very strong directors. I like to keep looking for those challenges.”

She also feels strongly about advocating for editors to ask for an editor’s cut of any film or television project they work on, noting that she always offers two versions of the editor’s cut: one as it was scripted, and the other as a more freely rearranged and reinterpreted version she feels is worthwhile to present. For her, the editor’s cut can be used “as a basis for constructive and creative dialogue with my director [and] for checking my director’s creative parameters and endurance.” This helps optimize the time editors have with directors and helps to “make the movie fly.”

“The scandal of last year’s Oscars (with the film editing award being excluded from the main broadcast) was a reality check on where the respect for our craft stands in this industry,” she said. “I can’t say this any clearer: There is no movie without editing. The editor’s cut matters, and I want today’s and the next generation of editors to be vocal about this. Look for a way to be more visible and to demand what we need to do our job better.”

Kristin Marguerite Doidge teaches journalism and is the author of “Nora Ephron: A Biography.”