By Rob Callahan

Late on an early August morning, a Douglas DC-9 made its way through cloudy skies above northern New Jersey, on approach to land at LaGuardia Airport. The Air Canada flight from Toronto carried 76 souls aboard. Flying through clouds at 15,000 feet, the pilot was startled to discover another DC-9, outbound from LaGuardia, at the same altitude. The two aircraft avoided an accident — the pilot of the outbound New York Air DC-9 never even saw the Air Canada jet sharing its airspace — but the near-miss was close enough to make news the next day.

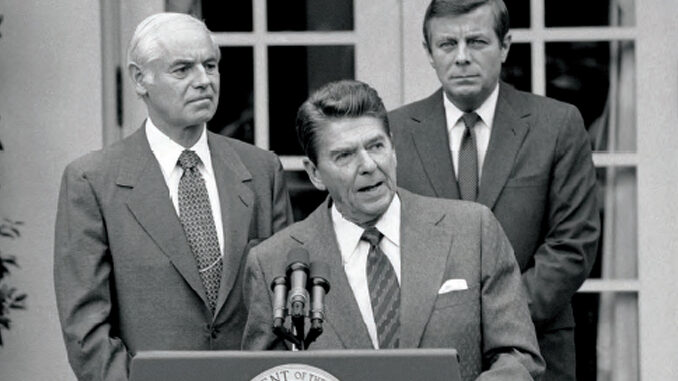

At the very same hour, about 200 miles southwest of where the two planes passed in perilous proximity, the new President of the United States, not yet seven months in office, was making news of his own. Flanked by the Attorney General and the Secretary of Transportation, Ronald Reagan addressed a throng of reporters at a press conference in the White House’s Rose Garden. The President — who retains to this day the distinction of being the only former labor union leader to later be elected as the nation’s chief executive — stood at the podium and issued a stern ultimatum: “Those who failed to report for duty this morning,” he said of striking air traffic controllers, “are in violation of the law, and, if they do not report for work within 48 hours, they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated.”

This summer marks the fortieth anniversary of what many regard as, in the words of historian Erik Loomis, “the greatest disaster in American labor history.” Having voted in July to reject a tentative agreement, the members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) walked off the job on the morning of August 3, 1981. Their fateful work stoppage continues to loom large in the consciousness and conscience of organized labor four decades later.

The controllers knew that the safety of air travel depended upon their highly-skilled and extraordinarily taxing work, as the LaGuardia incident made plain. Indeed, the connection between air traffic controllers’ working conditions and public safety had largely motivated the formation of their union in 1968. In the round of talks that led to their ill-fated 1981 strike, the controllers had sought shorter working hours and the option to retire earlier — changes that would have not only improved the quality of life for these employees working unusually high-pressure jobs but would have also enhanced the safety of the skies. The agreement that the controllers voted down would have granted them wage increases more than twice those of other federal employees, but it fell far short of the controllers’ goals.

PATCO’s slowdowns and work-to-rule actions [the practice of working to the strictest interpretation of the rules as a job action] of previous years had had dramatic impacts on air travel and had won the union significant gains. The controllers had hoped that their 1981 walkout would hobble the aviation industry and would force the Reagan administration back to the table to negotiate better terms. PATCO had defied the mainstream of the labor movement to endorse Reagan for election the previous year, and they banked on the prospect that the ecoonomic impact of a strike combined with the goodwill they procured through their rogue endorsement would persuade Reagan to buck the ultra-conservative anti-union elements in his own administration who refused to accede further to the union’s demands. (Indeed, in 1980 then-candidate Reagan had written the union a letter broadly supportive of the controllers’ bargaining objectives.) Although PATCO had made little effort to court public opinion or even secure the support of other labor unions in the lead-up to the strike, the controllers were convinced that they would be able to defy the legal prohibition on federal employee work stoppages and exact the terms they sought.

The controllers miscalculated. In an era in which unabashed, unrestrained union-busting had not yet become a tenet of Republican Party orthodoxy, PATCO had not anticipated the degree to which the administration would refuse to yield as a matter of principle. Notwithstanding the strike’s immediate impact upon air traffic, or the long-term costs and safety consequences of firing and replacing more than 11,000 highly-trained professionals, Reagan remained resolute.

The controllers miscalculated. Reagan remained resolute.

The close call outside of LaGuardia on the strike’s first morning was not an isolated incident. PATCO inventoried a number of mid-air near-misses the union attributed to inadequate skeleton crews of supervisors and scabs working the air traffic control towers. Confidential reports from a safety committee of the Air Line Pilots Association raised grave concerns about the ability of replacement controllers to ensure the integrity of the system. National Transportation Safety Board hearings even revealed evidence suggesting that error in National Airport’s air traffic control tower may have been a contributing factor in the crash of Air Florida Flight 90 into the Potomac River in January of 1982, killing 74.

In addition to their implications for air safety, the PATCO strike and Reagan’s decision to squash it exacted enormous economic tolls. Approximately 7,000 flights — roughly half of the nation’s air traffic — were cancelled on the first day of the strike alone. Estimates of the strike’s immediate impact placed the airlines’ pooled losses at roughly one billion dollars per month. The cost to taxpayers just for the training of replacement controllers eventually amounted to $2 billion. The economic ripple effects of the slowdown in air traffic are harder to quantify, but colossal. At the start of the strike, the differences between PATCO’s contract proposals and the Reagan administration’s offer totaled $534 million — a huge sum, but merely a fraction of what the government and society at large would pay as a consequence of Reagan’s refusal to negotiate. Historian Joseph McCartin asserts that, “It cost more to break the PATCO walkout than any other labor conflict in American history.”

But, costs be damned, the strike was broken, and broken decisively. While it would take more than a decade before the Federal Aviation Authority would be able to return staffing levels to their pre-strike state, PATCO was widely deemed defeated almost immediately after Regan followed through on his threat to fire the strikers en masse. On August 30th the editorial page of The New York Times declared “President Reagan has done it: he has proved that the air controllers’ union could not extort a favorable wage settlement by stopping the planes.” The editorial praised the President’s hardline refusal to bargain as “a commendable precedent,” although it advised the President to allow defecting PATCO members to return to work under their prior terms of employment, rather than banning them from air traffic control jobs for life. Reagan, though, showed little interest in moderating his stance. The strikers would be barred for life from future re-employment (until Clinton rescinded that order 12 years later), and their union was stripped of its negotiating rights and fined into insolvency.

Reagan’s rout of the PATCO obviously had devastating consequences for the 11,000 air traffic controllers who lost their livelihoods. But it also had profound reverberations beyond its direct impact upon those workers and their families. In a sense, Reagan not only broke a strike, but broke the prevailing model of industrial relations. Labor relations in the period of post-war prosperity had at least notionally been predicated upon an idea of industrial pluralism. Writing in the June 1981 issue of The Yale Law Journal, Katherine van Wezel Stone defines “industrial pluralism” as the view that collective bargaining is self-government by management and labor: “management and labor are considered to be equal parties who jointly determine the conditions of the sale of labor power. … [M]anagement and labor, both sides representing their separate constituencies, engage in debate and compromise, and together legislate the rules under which the workplace will be governed.”

It cost more to break the PATCO walkout than any other labor conflict in American history.

Arguably, this idea of industrial pluralism — of management and labor as equal partners in jointly steering American industry — never truly described the relationships of power in the U.S. economy. But capital had at least felt an obligation to perform pro forma gestures acknowledging the legitimacy of organized labor as an opposition party. Reagan’s response to PATCO shattered such norms. The President’s example emboldened private sector as well as public sector employers to forgo negotiations in favor of obdurate ultimatums.

“It launched a new era of union busting in the United States,” in Erik Loomis’s words, and “marked the beginning of the modern corporate war on organized labor.” Such an understanding of PATCO as a watershed isn’t limited to labor’s boosters; more than 20 years after PATCO, the arch-conservative commentator George Will crowed that Reagan’s defeat of the strike “altered basic attitudes about relations between business and labor … produc[ing] a cultural shift, a new sense of what can be appropriate in business management.” If labor conflict in the era of post-war prosperity was characterized largely by skirmishes for the high ground as labor and capital sought to gain relative advantage, in the time of Reagan and beyond, employers had both license and inspiration to wage wars of annihilation. Capital came to see its objective as not merely to gain the upper hand over unions, but to destroy organized labor utterly.

It would be a gross oversimplification to say that the PATCO debacle is the reason why the labor movement in the U.S. finds itself in its presently diminished state. Organized labor faced challenges pre-PATCO, and a host of factors have contributed to the diminution of unions’ presence and power in the economy over the course of recent decades. But the consensus is clear that the episode represents a key inflection point in labor’s decline. As a percentage of the nation’s workforce, the rate of unionization is now less than half of what it was at the time of the PATCO walkout. Notwithstanding isolated victories and progress on particular issues, labor has largely spent the past forty years since PATCO — for most of us, the entirety of our working lives — cursed to wander in the wilderness.

Why did PATCO fail so spectacularly? Is it simply a story of hubris, the controllers overplaying their hand? Is it essentially a story of individual resolve, Reagan’s steely determination to incur any cost for victory? Is it fundamentally a story of disunity, the failure of labor to close ranks and present a unified front in the fight? Or is it ultimately a story of seismic forces that transcend organizations or even nations, the ascendency of neoliberalism as the dominant world order? I don’t pretend to have authoritative answers, or even very good ones.

Perhaps the lesson to take away from the disaster of PATCO is that paradigms shift, subtly at first and then conspicuously.

Why did PATCO fail so spectacularly?

For the optimists amongst us, there are signs — tentative and attenuated though they may be — that perhaps labor’s years of wandering through the desert could come to a close, that perhaps a new epoch is nigh. Public sentiment now weighs heavily in favor of unions, with polls showing support for unions currently as high as at any point since Reagan took office; close to two-thirds of Americans are in favor of organized labor, according to Gallup, even though less than 10 percent are union members themselves. The wave of strikes in education that washed over the country in 2018 and 2019 captured the imagination and won the backing of working folks nationwide; the #RedForEd movement represented the largest collective action amongst public servants since the postal workers’ wildcat strikes of 1970 ushered in an era of super-charged public sector organizing. Activism around issues of social injustice is at levels not seen in generations, and activists are smarter than ever about articulating the ways in which the struggles for racial justice, gender justice, justice for immigrants, and justice for workers are all inextricably intertwined. An embrace of unions and suspicion of laissez-faire economic policy is especially pronounced amongst our youngest workers, for whom faith in the future of the planet, never mind the American dream, has been profoundly shaken.

Perhaps most markedly, the pandemic has interrupted our way of living, disrupted our labor markets, and thrown into sharp relief the limitations of neo-liberal reliance upon the free market to provide for fundamental human needs. The coronavirus relief package passed earlier this year represents the most ambitious anti-poverty public policy since the New Deal, a governmental response to economic inequality that would have been inconceivable even as recently as the Obama era. In a dramatic break from recent history, employers are now openly competing for workers by raising wages. It’s far too early to cast him in the role of the anti-Reagan, but it’s no coincidence that the current political climate and the devastation of the plague led to the election of a political figure, Joe Biden, who has publicly vowed to be “the most pro-union president you’ve ever seen.”

An organizer ought not be a pollyanna, and I’m not about to assert that labor’s long years of setbacks are now behind us. Nor am I naive enough to think that Biden might be relied upon to reverse the damage done by Reagan and his associates, acolytes, and heirs, who are legion. But for those of us who have only ever known a circumscribed and cowed labor movement, it is crucial to look back upon our history for a reminder that it wasn’t ever thus. Forty years after the PATCO catastrophe signaled an era of erosion in the clout of working folks, we owe it to ourselves and to our progeny to seek opportunities to usher in a new age, one in which future generations might live and work with dignity and power.