by Rob Callahan

“There’s no place like home,” Dorothy avows, willing herself back to the banal comforts of Kansas. Now, as we try to will ourselves out of the shared nightmare of this pandemic, 12 months (at this writing) after Los Angeles issued its initial stay-at-home order, I don’t doubt Dorothy’s conviction that there’s no place like home. The question now is whether there exists, in fact, anyplace other than home. The home occupies all, being now not merely a domicile, but also simultaneously a bunker, a hermitage, and an office.

One year into this catastrophe, I number myself among the fortunate ones: My family and I have avoided falling ill, and I have work. This global ordeal tries my patience and weighs heavily upon my spirit, but I know that I’ve no personal cause for complaint. It has exacted far more terrible tolls from far too many. Even those of us who remain comparatively unscathed, though, are not unchanged. One of the subtle but significant impacts the pandemic has had upon me is the way in which it has altered my understanding of that place like no other, home.

Like a lot of our members who have had employment during the pandemic, Editors Guild staff members have been working from home. Most of the work we do can be performed remotely, and remote work affords obvious advantages in terms of safety. What’s less obvious is how working from home affects work-life balance, how it changes our relationship to our work and to our coworkers, and even how it challenges our idea of home itself.

Yeoman farmers, feudal serfs, or even the traditional artisans who first formed guilds would not have fully shared our definition of “home.” But, since the advent of industrial capitalism, the notion of home has largely come to be understood as a space distinct from the worksite at which we labor for wages. Home is where one lives, sure, but “living” isn’t just about drawing breath. (In pre-pandemic times, many of us would spend the majority of our waking hours in workplaces; we didn’t properly “live” there.) Home is the space in which we belong during those periods of time when our time belongs fully to us – that is, when we’re not selling our time and talents to an employer.

If industrialization helped to define “home” as the place we live when we control our own time, a post-industrial pandemic has upended that understanding, perhaps permanently, for those of us with jobs that lend themselves to remote work. That transformation, to be sure, isn’t all bad. Obviously, working from home has been instrumental in helping us to remain healthy during a plague. Moreover, it has freed us from the drudgery of daily commutes, and it has given us more opportunities to spend time in proximity to those we most love. I’ve been relishing the lunches with my wife and kid, and it’s great being able to prune tomato plants in my garden at the same time that I’m on a conference call. In many respects, working from home is a luxury.

The additional technology upgrades such as virtual offices have also made remote and hybrid jobs a lot easier. Now the whole workforce can connect online and function in a similar way as one will in the office. We can hold meetings, videoconferences, and discussions, virtually without being together in the same space. A few services may also provide London virtual office to its members so that they can keep their personal address off the internet and public records. Anyone can easily get a virtual office for your company by choosing monthly plans depending on your requirements.

But the collapse of the physical distinction between home and work can make maintaining the equilibrium of work-life balance trickier. I’ve spoken to many post-production professionals working from home who speak of increased pressures, implicit or explicit, to work through breaks, to work irregular hours, or to put in unpaid overtime. When we work where we rest, it gets harder to police the boundaries between the time that belongs to our employers and the time that we retain for ourselves. Some of them mentioned that in order to help them cope with the stress that they might feel to be working consistently that they had invested in alternative medications similar to CBD gummies or crystal therapies. Whether these treatments help I’m not sure but for my co workes they seemed to believe in them. It shows perhaps that getting a work-life balance when fully working from home might be harder than most could think.

More salient to the question of organizing, perhaps, is how remote work affects our relationships with coworkers. Even as our working lives now encroach upon the sanctuary of the home, colleagues are more distant, and connections between coworkers less organic. Our family members are perhaps more like workmates, while our workmates are less like family.

Organizing is all about forging solidarity with coworkers to exercise more power vis- -vis bosses. With the world of post-production coming increasingly to look like a cottage industry-consisting of colleagues each sequestered in their individual homes, hither and yon, invisible, or even completely unknown to one another-can organizing new shops even be possible?

I am pleased to report that, yes, remote workforce management and organizing can happen and has been happening – even while remote work has kept post employees physically separate from each other. Just as corporate offices have remote work management software to maintain their productivity, production crews are also adapting to the new situation creatively.

A lot of that organizing has taken place in conjunction with production crews working in more-or-less traditional (albeit socially distanced) settings. Unscripted shows-titles such as “Bake Squad” and “Ellen’s Next Great Designer”-have been flipped in recent months, largely on the strength of in-person production crews demanding union protections on those shows. Such campaigns look much like the IATSE’s pre-pandemic organizing of individual shows, in which production crew members on set coordinate with post employees working off-set to present their employer with an ultimatum: sign a union contract or your show doesn’t get made.

But we also have a couple of recent examples of organizing wins driven entirely by post-production personnel working remotely. One such was the January strike of the “Unfiltered” crew.

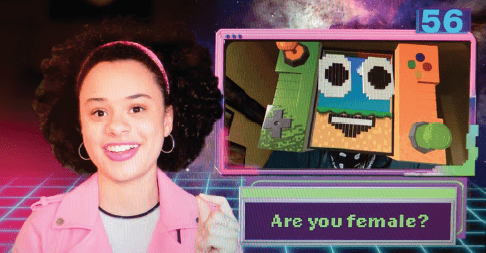

“Unfiltered,” a new game show for Nickelodeon, is an instance of the industry innovating new forms of content intended to be pandemic-proof: there is no set, no production crew, and hence no risk of viral exposure. The show’s on-screen talent shoot themselves in their own homes using green screens and camera and lighting kits sent to them by a vendor for the production. A crew of assistant editors, graphics artists, and editors (all working from their respective homes) then cobbles together the remotely-filmed footage with a barrage of motion graphics. The effect is a televised approximation of the app-mediated means by which members of an extremely online generation relate to one another. The show is, essentially, all post.

The show may be pandemic-proof, but it wasn’t organizing-proof. Guild organizers spoke to members of the show’s post crew towards the end of the show’s first season last fall. We gathered, virtually, to discuss organizing over the course of multiple Zoom sessions. The clear consensus among the crew was that the show, which was proving itself a success for the network, relied heavily upon their skills and efforts. Notwithstanding their instrumentality in the show’s success, the post personnel were working long hours at wages well below industry standards. And, of course, in the midst of an unprecedented health crisis, they weren’t receiving any contributions towards Motion Picture Industry health coverage.

The remaining schedule in that first season didn’t bode well for our leverage demanding a union contract, but the crew decided and pledged to one another that they would unionize early in the second season in the event that the show was renewed. It did get renewed, and, in the first week of January, the day before the first episode of the second season was to air, the IATSE notified the company that its crew demanded union recognition. When the company didn’t immediately grant recognition, the crew went on strike.

We usually say that a crew “goes out” on strike, or that they “walk off” a job. But those spatial terms don’t quite fit when the strikers don’t, in fact, go anywhere. And of course there was no picket line, as there was literally no worksite to picket. In the absence of traditional modes of action-workers physically accompanying one another away from the workplace and physically patrolling the workplace’s perimeter to discourage would-be scabs-intra-crew communication became all the more crucial. Folks had to keep in contact to be confident that they stood together, even while physically apart, and to know that the show couldn’t go on without them. Ultimately, though, it didn’t matter if the crew members were on a picket line or on their living room couches. What mattered is that they were acting in concert and their work wasn’t getting done.

The network recognized that the crew’s action jeopardized the employer’s ability to deliver a hit show in time for scheduled air dates. Two days after the strike began, we had an agreement to return everyone to work under a union contract. As a result, the ten editors and assistant editors saw increases to their base pay ranging from 50% to 70%, plus vacation pay, holiday pay, and, of course, MPI health and retirement benefits. It was our Guild’s first strike conducted entirely over Zoom-likely among the first of such strikes for any union-and it scored a huge payoff for the crew.

But organizing wins don’t necessarily involve work stoppages. A case in point: only a few weeks after the “Unfiltered” strike, we won union recognition for a nation-wide group of 50 editorial employees working for the animation studio Titmouse, Inc., a prolific producer of adult-oriented animated programming, including such titles as “Big Mouth” for Netflix.

The animation sector of our industry, already experiencing boom times before the pandemic, was quick to embrace remote work. Without physical production crews, physical sets, and on-camera talent, retooling animation for working from home was relatively easy. When stay-at-home orders brought all of live-action production to a complete stand-still, animation only began picking up the pace.

The Titmouse organizing-from-home effort faced challenges that wouldn’t have pertained to organizing at a traditional worksite. There was no water cooler at which coworkers could meet and establish connections. There were no after-work happy hours at which they could casually share stories about workplace concerns. Some of the Titmouse employees had been working at the company for years, but many others only began there more recently and had never had the opportunity to meet any of their coworkers in person. Text messages, emails, and meetings via videoconference had to suffice for building a community and consensus capable of effecting change at their employer.

But the Titmouse editorial crew did that work of building solidarity, culminating in an overwhelming majority of the employees signing electronic union cards in a virtual vote for Editors Guild representation. We sent the company correspondence informing them of the crew’s choice in late December. A few weeks later, we had reached an amicable agreement for management to recognize the crew’s choice to unionize, based upon a neutral third party’s verification that a majority of the employees in question had signed cards. At the time of this writing, Titmouse’s editorial employees are preparing to negotiate their first union contract at the company.

Collective action is a prerequisite for meaningful change, and there are challenges to achieving such collective action when workers are working in individual isolation. As an organizer, I’d much prefer to meet with workers in person and look them in their eyes. More important, I’d prefer that the leaders on our organizing committees would have direct, unmediated access to their colleagues as they’re reaching out to bring coworkers on board with the organizing effort.

But it’s also perhaps true that the lives of involuntary sequestration we’ve lived over the past year have helped us to recognize how crucial it is to remain connected to those with whom we share common interests. These months have often been lonely ones, but that loneliness has, maybe, made us more eager and more innovative in our efforts to forge bonds that make us less isolated, more powerful.

Even from the bunkers of our living rooms-pressed into service as working rooms-organizing finds a way.