by Peter Tonguette

At first blush, it might seem unlikely that editors and cinematographers would have much to say about working with each other. Because of the bifurcated way in which most films and television shows are made, with production and post-production each functioning more or less independently, they seldom have occasion to work together on a one-on-one basis.

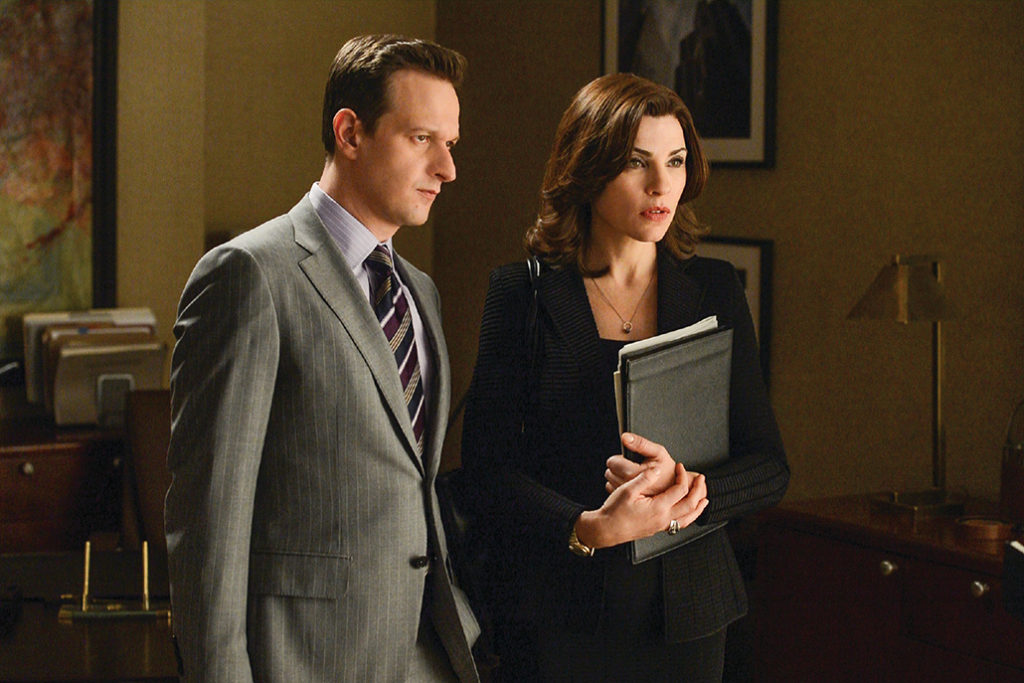

That does not mean, however, that they do not collaborate. Each depends on, and feeds off, the work of the other. In recent interviews with CineMontage, this was a point emphasized time and again by the editors and cinematographers of two popular episodic television shows: The Good Wife, which will begin its fifth season September 29 on CBS, and The Newsroom, which had its second season premiere July 11 on HBO.

The Good Wife

The Emmy-winning drama The Good Wife, starring Julianna Margulies as a former attorney who goes back to the legal fold, shoots in New York, but post-production is handled in Los Angeles. According to Scott Vickrey, A.C.E. — who, along with David Dworetzky and Matthew Kregor, has cut the majority of episodes since the series premiered in fall 2009 — this means that the editors speak with the show’s cinematographers rarely, with the most in-depth talks coming at the beginning of a season when certain stylistic parameters (such as shot sizes) are discussed in tandem with producers Michelle King and Robert King. They also confer if there is a problem.

“Most of the conversations,” Vickrey says, “come up when something is needed or if shots are missing or if there’s been some lighting issues, where we look at something, and we go, ‘Whoa, this is very dark. Is this really what you intended?’ or ‘We’re going to need a few more shots here to really make this work.’”

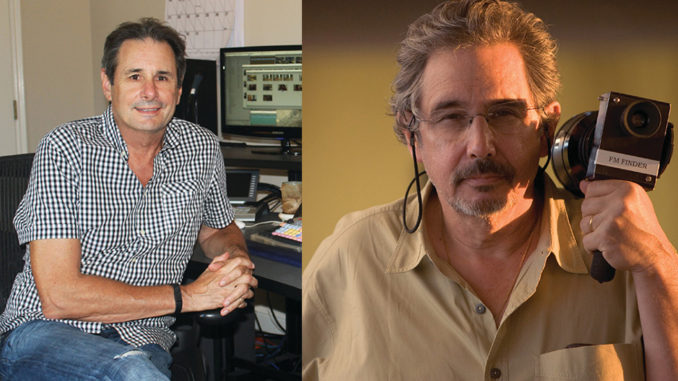

“They’ll send me a little picture, and they’ll say, ‘Take an insert of this,’” explains Fred Murphy, ASC, a veteran of feature films who, like Vickrey, has been on The Good Wife since the beginning. Since each episode is filmed in only eight or nine days, with a first cut shown to the director only two days after that, it is understood that not every shot can be obtained during principal photography.

“One thing with episodic is that they can’t always grab the inserts that are needed,” Vickrey adds. “But you know that you’re going to go back with a B unit and get anything that’s missing because you have standing sets, and you have the crew around for a very long time. On a feature or TV movie, once they’re done shooting, that’s pretty much it and everybody goes home. On a series, you can go back and get inserts and pick-ups that will help with the storytelling.”

Of course, that is not to say that Vickrey finds himself going back to Murphy too often with requests. “Fred really makes sure that he gets the coverage so you can cut the scene the way you’d like to,” Vickrey notes. “There are definitely options there. You don’t get locked into, ‘Well, we’re just going to do this in one master, and that’s it.’”

For the courtroom scenes that make up much of The Good Wife, the editors may receive up to four or five hours of dailies per day, drawn from three cameras. While Murphy takes his time in lighting and staging a scene, Vickrey feels that his methods pay off in the long run. “Fred is going to give you what you need and you’re not going to have to go back and re-shoot,” he says.

At the same time, Murphy is attuned to what the editors do not have a use for, based on observing which shots are selected and which are omitted. “You have very little time to do a lot of this stuff,” Murphy comments. “You try not to do things that are going to end up on the floor.” For example, Vickrey points out that high-angle courtroom shots tend to be used only at the beginning or end of a scene, so there is no need for such shots to cover the whole scene. “I think that Fred sees how the shows are cut together,” Vickrey says. “He knows what’s really important.”

For his part, following the first season, Murphy found that wide shots without dialogue seldom made it to the final cut, so he devised ways to make sure the dialogue in a scene is incorporated into those wide shots. There are too many time pressures, he says, to shoot “some shot that might be beautiful and might be really interesting, but is never used.”

“[Editors are] able to structure all these moments, and all these peaks and valleys of the performances, that give it the depth and the character and the emotion that I don’t necessarily get to see… I’ll see a great performance — and most of the performances are great — but how it intercuts with some of the other angles and some of the other characters, I don’t necessarily get that kind of privilege.” – Todd McMullen, cinematographer

Murphy refers to the kind of unspoken dialogue that goes on between the cinematographer and editor. The order of the shots “should be self-explanatory, if you do it right,” he observes. “The editor should see it and say, ‘Ah.’ Even if he’s not involved in the conversation.” Even so, Murphy enjoys seeing his work filtered through the eyes of others. “I’ve had some really good editors,” he reflects. “Really good ones. On a movie I did called Hoosiers [1986], the editor, Tim O’Meara, A.C.E., was part of making that movie good. He was a terrific editor, and very helpful and understanding in helping make that movie work.”

But if Murphy values editing, Vickrey prizes what this particular cinematographer has brought to The Good Wife. “They love him on the show,” Vickrey says. “He is a DP who I feel really does take time to light the scenes properly. Everything is very consistent. He’s great at capturing the mood of the scene through his lighting.”

In 2012, Murphy brought aboard former gaffer Tim Guinness (who had worked in that capacity on The Good Wife) to shoot every other episode, alternating with Murphy. “It makes a big difference for both of us,” the cinematographer laughs. “We’re no longer exhausted.” As far as Vickrey is concerned, Guinness’ work fits in perfectly. Looking at dailies, there are times when he can’t tell whether Murphy or Guinness shot a particular episode. “It’s amazing how consistent the work is between the two DPs,” the editor says.

The Newsroom

For editor Howard Leder, one of several editors who has worked on The Newsroom over the course of its two seasons, the bulk of the editor-cinematographer collaboration also occurs after the production of a given episode has ended. “Most of our interaction is on the screen,” Leder says of cinematographer Todd McMullen, who has shot every episode of the series’ two seasons (except for the pilot). “I see what they’ve done and react to that in the cutting room.”

In the case of The Newsroom, starring Jeff Daniels, Emily Mortimer and John Gallagher as part of a cadre of on- and off-air talent on the fictitious TV show News Night, there is a lot for the editors to react to. The average episode shoots for 10 days, and it is not unusual for numerous takes to be shot. Since series creator Aaron Sorkin specializes in writing long scenes, Leder notes, “With three cameras on a five-page scene, if they shoot 20 takes, that is a huge amount of footage that you’re going through.” He adds, “If they do 20 different versions of a scene, chances are you’re going to use a lot of those in different pieces. You’ll need take one because it’s so different from take eight.”

Adopting a style similar to that of another series he worked on, Friday Night Lights, McMullen moves fluidly through a scene, whipping from one character to another. “That’s what we describe as ‘the show,’” Leder says. “This kind of movement and letting the camera do a little bit of the editorial work in moving the eye around.” The main newsroom set is always teeming with action. “We have days when our principals show up — like Alison Pill or John Gallagher — and they’re basically just extras,” Leder continues. “Your character is there for the day working, so you just need to be there in the background.”

McMullen gives a free hand to his camera operators so they can pick out points of interest in this atmosphere. “I try not to give them too much instruction because they’re another element in telling the story,” McMullen comments. “I don’t micromanage my guys because all of a sudden the focus puller might pull focus to somebody in the foreground for a really wonderful moment.”

With rare exception, McMullen shoots with two cameras and tries to use three when the location permits. He relishes getting cross coverage. “As far as the continuity, it’s a lot easier for Howard to cut that stuff together because it just runs right through,” he explains. “He’s got the same performance on all three cameras.” In part, his methodology dictates the style of the show, with the camera hanging back from the action. McMullen adds, “If the cameras are on top of the performers, you can’t obviously get a couple cameras in there. We try to scoot back a little bit and maybe shoot through some things, get some nice foreground going, and go from one person to another, and keeping it alive that way.”

Since the entire season is in the can before the first episode airs, the editors can revisit the dailies from an earlier episode they may have put aside. “The first version of scenes you do can be very good, but then at some point there’s often the question, ‘Can we go deeper in this scene?’” Leder says. “So we re-open the footage and dig back in and maybe find a take where they tweak the emotion in a different way.”

Todd McMullen.

In the second season, which takes place over the course of last year’s presidential election, one key character was brought more into focus after Leder became more familiar with him. “There is an overarching story that pushes the entire season, and there’s a character who is kind of in the driver’s seat in that,” the editor says. “In my initial passes on him, I had kind of underestimated him. After I saw and was reading later episodes, I felt I needed to bring him to the foreground a little bit more.”

Leder points to a scene between Sam Waterston and guest star Jane Fonda in the second season finale. “There are dozens of ways you can get through it, and they would all be valid,” he explains, adding that the entire cast gives post-production a wide variety of choices, while some actors give them a “spectacular” variety. “With somebody like Jeff Daniels, he’s so good that you could use virtually any of the takes.”

During shooting, McMullen says that he finds it easy to lose sight of the big picture, which is why he enjoys seeing his work interpreted by the editors. “They’re able to structure all these moments, and all these peaks and valleys of the performances, that give it the depth and the character and the emotion that I don’t necessarily get to see,” he acknowledges. “I’ll see a great performance — and most of the performances are great — but how it intercuts with some of the other angles and some of the other characters, I don’t necessarily get that kind of privilege.”

Courtesy of HBO

In supervising two or three camera operators, the cinematographer is liable to miss certain moments that are ferreted out by the editors. “I might be looking at one camera, while another one just happened to pan over or tilt down and find something that the character was doing — and then it got used in the cut,” he remarks. “It is like, ‘Oh, wow! Good eye, man; you found that.’”

Leder concludes, “We’re two of the horses in the team that is pulling the chariot.”