by Ray Zone

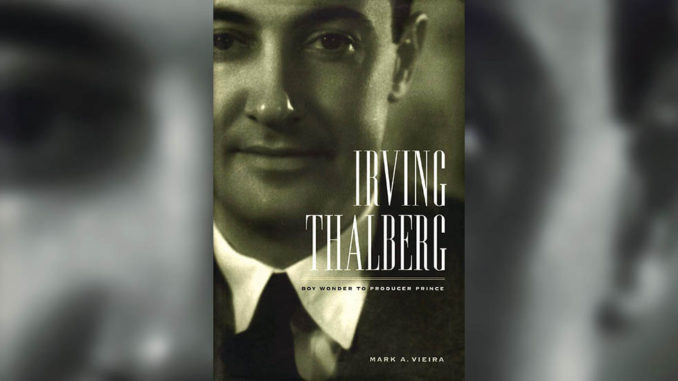

Irving Thalberg

Boy Wonder to Producer Prince

by Mark A. Viera

University of California Press

528 pps., hardbound, $34.95

ISBN: 978-0-520-26048-1

Mark A. Viera is the prolific author of numerous books about Hollywood film history, including Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood (Abrams: 1999) and Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic (Abrams: 2003). With his new book on Irving Thalberg, Viera has made a significant contribution to film history, particularly the growth of the star and studio system. This is a work that will have considerable interest for motion picture editors as well as students of motion picture culture.

Thalberg, as a very proactive producer, originated the function of the story editor. In addition, a large component of his success as an effectively engaged producer was his use of the preview to gauge audience reaction and the extensive use of re-takes and new line readings when he found them necessary. This attention to detail proved essential in Thalberg’s post-production methodology.

Viera’s book is studded with great anecdotes about Thalberg’s participation in the editing process, as well as historic editors. There is a wonderful story about legendary MGM editor Margaret Booth’s first day at work. This was in 1919, before the formation of MGM, when Thalberg and Mayer were working together at Louis B. Mayer Productions. At this time, Mayer’s studio was at 3800 Mission Road in Los Angeles, located adjacent to William Selig’s Zoo, where Mayer had rented space from the Selig Polyscope Studio.

“When novice film editor Margaret Booth came to Mayer from D.W. Griffith’s company in Hollywood, the remoteness of the strange little studio frightened her,” notes Viera. “She found out too late that Mission Road streetcars did not run regularly. After her first day in East Los Angeles, she made a tearful journey back to 17th Street in Los Angeles and then telephoned head editor Billy Shea. ‘My mother doesn’t want me to work with you because I can’t get home!’ blurted Booth. Only when Shea promised to drive her both ways did she agree to return.”

Irving Thalberg did not innovate the use of the sneak preview for motion pictures. But he previewed nearly every film that was made under his aegis.

Thalberg’s intervention in the editing process saved many productions. The 1924 Metro-Goldwyn production of He Who Gets Slapped, for example, was excessively somber and its downbeat nature made it “a dubious candidate” for the Capitol Theatre’s fifth anniversary gala premiere slated for November of that year in New York City. After viewing the initial cut, “Thalberg set his jaw, and according to studio publicist Frank Whitbeck, ‘he disappeared into the cutting room and didn’t come out for two days and a night,’” writes Viera. As a result, He Who Gets Slapped was Metro-Goldwyn’s “first smash hit.”

Another big Metro-Goldwyn production that Thalberg saved with his editing expertise was the 1925 epic Ben-Hur. After suffering a heart attack, Thalberg recuperated “at the Crenshaw Boulevard home of supervisor Bernie Fineman and his wife, actress Evelyn Brent. The reason was that the ‘sickroom’ there had the ideal dimensions for the projection of movies onto the ceiling over the bed. ‘Irving was still too weak to sit up,’ recalled Lucien Hubbard. ‘He had to lie on his back and look at the rushes of Ben-Hur on the ceiling.’”

Actress Marion Davies visited Thalberg while he was recuperating. “The cutter was there and they were working like mad,” recalled Davies in 1951. “He spoke to the film editor; ‘Cut this here and cut that there and two inches here and…’ This went on until they came to the end of the reel.” Ben-Hur also became a massive hit. Screenwriter Dorothy Farnum later called Thalberg “the skilled surgeon who cuts to heal.”

Thalberg did not innovate the use of the sneak preview for motion pictures. But he previewed nearly every film that was made under his aegis. Frequently, if a preview was negative, Thalberg returned to the studio and, working with a screenwriter, dreamed up new scenes to fill holes in the story. These new scenes were then shot and subsequently screened in a new cut of the movie at another sneak preview. “‘We were always previewing,’ said Margaret Booth. ‘You’d preview two, three, four times until you got it right.” Sets were not struck until it became apparent that re-shooting was finished. It was a difficult and time-consuming procedure but it saved many marginal productions and ultimately proved to be a sound business practice.

Mark A. Viera’s book is studded with great anecdotes about Thalberg’s participation in the editing process, as well as historic editors.

Thalberg and an editor would typically take a “Big Red” trolley to the previews throughout Southern California. By 1932, the preview trolley rides had become so frequent that the Pacific Electric System laid a spur directly onto the MGM lot. On the return trip back from one preview, a producer wailed out, “God, we have a stinker!”

“‘What are you talking about?’ snapped Thalberg. ‘It’s great! This is going to make a marvelous picture. The second reel, the third reel, the sixth reel, and the eighth reel are wonderful. We have to fix up the beginning a little, the middle a little, and the end a little––and we’ll have a great picture.’”

Viera’s fine history provides an insightful look into this legendary producer and a beautifully limned portrait of studio production in the classic years of Hollywood.