by Peter Tonguette

Louis B. Mayer was crying.

The boss at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer — a man both admired and feared all over Hollywood in the 1930s — listened as a female studio employee read him a story. As the most powerful man in the movie business, Mayer was on the receiving end of stories all day long. He heard everything, and the ones he liked best found their way onto the soundstages of his fabled studio and, eventually, onto screens in movie houses across America during the Great Depression, where they spurred the dreams and fantasies of millions of people.

But this was no ordinary story, and the teller was no ordinary woman. She was the head of the story department at MGM, and she had her hands on material that would eventually become a beloved Oscar-winning film.

The story that made Mayer weep was an early outline of William Saroyan’s screenplay that would eventually evolve into “The Human Comedy.” Eventually released in 1943, the heart-tugging coming-of-age story starred MGM stalwart Mickey Rooney as a telegram messenger who often was the bearer of death notices and other bad news. The script won an Oscar, and the film became an audience favorite.

That day, though, Mayer was the first audience member to tear up at “The Human Comedy.” It wasn’t just the words that affected Mayer. There was something about the way the tale sprang to life as told by the woman who was reading it.

Who needed Mickey Rooney? Mayer had Kate Corbaley.

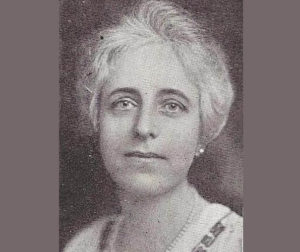

Today Corbaley’s name is unknown except to a small cadre of film scholars, mainly those who write about the life and legend of Mayer, but in her day she was considered a major player—a gate-keeper, in fact, who helped decide what movies got made and who appeared in them. During those days, at the summit of the Studio Era, Clark Gable and Greta Garbo ruled the screen, but Corbaley had something to say about what they did and when.

She had won the ear of the boss at the top studio in Hollywood at a time when women were often forced into domestic roles at home or, when they did enter the workplace, were relegated to perfunctory administrative tasks. With a literate background and a talent for cutting to the heart of the matter, her opinions on source material — novels, magazine articles, plays — could provide that first puff of wind that could make a project set sail — or the wisp of disapproval that would keep it anchored in harbor.

Her command of projects was legendary: In a 1937 Los Angeles Times column, movie critic Philip K. Scheuer wrote that Nelson Eddy knew 400 songs by heart, Eleanor Powell had 1,000 dance-step combinations down pat, and Corbaley had managed to memorize the plots to over 5,000 novels and plays.

Equally important to Guild members, Corbaley functioned as one of the industry’s first studio story analysts. Early female picture editors, like Margaret Booth, could save a film after the fact, but Corbaley was one of the very few given the responsibility of deciding whether a project should even be shot at all. Like modern-day story analysts — a classification represented by the Motion Picture Editors Guild since 2000 — Corbaley was tasked with determining whether a story was worthy of being turned into a screenplay, or whether a screenplay should make it before cameras.

It was a vital role, if an unheralded one.

“She is nonexistent, insofar as the motion-picture public is concerned,” wrote Gene Fowler, who made Corbaley the subject of a write-up in gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky’s “Hollywood” column in 1938.

“She does not strut among the fashion-plate sirens of the preview, nor does she scream for recognition in the conference when the scenario hacks make great kennel-sounds while fighting for the bones of story credit,” Fowler continued. “Yet Irving Thalberg once said that Kate Corbaley was the most important person in the entire studio.”

According to Saroyan biographers Lawrence Lee and Barry Gifford, Corbaley earned the nickname of “Mayer’s Scheherazade” for her ability to captivate Mayer with her gifts as a storyteller. “And she lived up to it,” the biographers wrote.

Indeed, according to Mayer biographer Bosley Crowther, Corbaley herself claimed that the studio boss wept on three occasions as she was reading Saroyan’s words.

During her years at MGM, Corbaley became a kind of reciter-in-chief to Mayer who, for all his acumen in matters of business, had an aversion to the written word. This is unlikely to have fazed Corbaley, who understood that she gleaned the pearls of culture for enterprising men, but not erudite ones.

She was among the contributors to the Palmer Photoplay Corporation’s guidebook “The Essentials of Photoplay Writing,” which offered the following pragmatic advice to would-be screenwriters: “Motion picture producers neither seek nor demand literary ability.”

Instead, Mayer preferred to listen to Corbaley transform the words on the page into pictures visible in his mind’s eye. The pictures flickered before him in glorious black-and-white: There was Gable making a dramatic entrance; there was Garbo reclining gracefully in a gown.

“She was his storyteller,” Scott Eyman, author of the biography “Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer,” said in an interview with CineMontage. “He enjoyed the way she would break a story down and tell it to him verbally. She could tell a story the way Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer would tell a story on screen.”

PIONEER AND POET

In 1878, when Kate Alaska Hinckley was born to industrialist William Hinckley and his wife Mary, movies didn’t yet exist — it would be another quarter-century before the exhibition of Edwin S. Porter’s early silent short “The Great Train Robbery.” Her unusual middle name reflects the circumstances of her birth: According to The San Bernardino County Sun, later her hometown paper, she entered the world on the steamer Alaska as it wound its way from Mexico to California.

Her ancestors were said to have included pioneers, and an independent streak ran in her immediate family. While Kate was still a toddler, her parents’ marriage came to an end; shortly thereafter, her mother wed banker William Hooper, whose name she adopted. “She was regarded as his own daughter among friends and residents,” The Sun reported.

Raised in San Bernardino and nearby Colton, Kate was a student of English literature — and was made a member of the honor society Phi Beta Kappa — at Stanford University, from which she graduated in 1900. She first found employment as a high-school English teacher in San Bernardino, but it was not long before she began receiving recognition as a writer in her own right.

In 1903, Kate — writing as Kate Alaska Hooper — published a work of verse in the magazine Sunset. The poem, “The Field of the Cloth of Gold,” included a paean to the land of her youth: “To blue California skies o’er head / Singing, nay, shouting the glad, free song / Of a land unscarred and young and bold / Here lies the real field of the cloth of gold.”

In 1905, Kate married engineer Charles W. Corbaley, with whom she had four daughters. The couple decided to move to Los Angeles, which would have a fateful impact on Kate’s career. Her storytelling instincts found an outlet in the burgeoning picture business. After years of accumulating bylines, Corbaley hit pay dirt after she entered her scenario “Real Folks” in a contest sponsored by Photoplay magazine and the Triangle Film Corporation: Not only did Corbaley walk away as the winner ($1,000 in prize money, or about $25,000 in today’s value) in a field of 7,000 applicants, but “Real Folks” was produced by Triangle.

In the Photoplay story announcing her win, Corbaley talked about her approach to writing: “The day has come when people want plays of character and not plays in which exciting plots are hung on wooden automatons.”

The produced film of “Real Folks,” starring Francis McDonald, Albert Lee, and J. Barney Sherry, may be lost to the mists of time, but Corbaley got a career out of the deal. In 1919, The San Ber- nardino County Sun blared the following headline: “Mrs. Kate Corbaley Has New Success as Writer.” That year saw the re- lease of two films on which she received story credit, “Gates of Brass” and “The False Code.” The paper noted: “Her many friends and admirers will be immensely interested and pleased in her latest advance in the writing game.”

FROM WRITER TO READER

Corbaley could lay claim to the status of hometown heroine, but as her career as a scenarist progressed through the teens and early ’20s, she also gained her share of “friends and admirers” in high places.

According to Gene Fowler’s column on Corbaley, producer Hunt Stromberg deserves credit for Corbaley’s switch from writer to reader. Already on the faculty and advisory council of the Palmer Photoplay Corporation, Corbaley teamed up with Stromberg as a “play reader and literary agent,” Fowler wrote. In 1926, after Stromberg began his tenure at MGM, Corbaley followed him to the studio. She never left.

Like today’s story analysts, Corbaley churned out overviews of possible projects, including, for example, an adaptation of Wilson Collison’s play “Red Dust.” In a synopsis she dictated in December of 1927, Corbaley deftly describes the work’s characters, plot, and setting, pausing to praise strong or recognizable elements, such as the “love conflict” at the heart of the property. Her instincts were, as ever, sound: Five years elapsed before a version of “Red Dust” reached the screen, but the resulting film is now considered a classic. Boasting the exotic setting of French Indochina, the spicy pre-Code production stars Clark Gable as a rubber-plantation boss ensnared in a love triangle alongside Jean Harlow and Mary Astor. Directed by Victor Fleming, “Red Dust” was remade by John Ford in 1953 (“Mogambo,” also starring Gable) and was selected for inclusion on the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry in 2006.

Corbaley advanced through the story department at MGM, with one promotion announced in The Los Angeles Times in connection with the hiring of Albert Lewin as an assistant to producer Irving G. Thalberg in 1928: “Kate Corbaley, novelist, playwright and pioneer screen writer, has been appointed Lewin’s assistant in handling the story department at the plant.”

Eventually, though, Corbaley was not only part of the story department but, in a sense, came to embody the story department. “She was one of the readers, what they called a reader at the time,” veteran MGM picture editor Margaret Booth said in an oral history with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. “She was one of them, and was the head one.”

A 1932 item in Fortune magazine described Corbaley — “a plump, ruddy lady who looks like a good character actress made up to resemble a county dowager” — as overseeing a staff of 12 readers tasked with sifting through assorted printed matter, from novels to articles in magazines and newspapers. According to The San Bernardino County Sun, around 2,000 stories cycled through the department each week — probably a very high estimate.

There were countless inter-office communications between Corbaley and Selznick, Mayer’s then-son-in-law who, years before he oversaw “Gone with the Wind,” managed his own production unit at Metro. The memos reflect the dizzying array of projects considered for production at the studio. In one memo from 1933, Corbaley suggests that the studio consider stars first (and, presumably, story second), proposing the idea of British actor Charles Laughton as Falstaff in an adaptation of Shakespeare’s “The Merry Wives of Windsor” and regretting that screen legend John Barrymore no longer had the looks to carry off Hamlet.

In another, from February of 1935, Corbaley advanced Sir Walter Scott’s novel “Ivanhoe” as subject matter that might satisfy audiences’ appetite for adventure — provided they could pry it from Universal. Selznick’s reply was encouraging, though “Ivanhoe” was not produced by the studio until 1952.

Corbaley always seemed to be peering around the next corner. Writing to Selznick in March of 1935, she makes mention of a new biography of English statesman Warren Hastings titled “Strange Destiny.” “Is it too soon to do another story of this type in that locale—or would you be interested in seeing a good outline of the book?” Corbaley wrote to her famous boss, who agreed it was too soon but asked her to revisit the idea in a few months.

The back-and-forth between story editor and producer suggests MGM’s eagerness to identify film-ready material. In another exchange from March of 1935, a few months after the studio had a hit with an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ “David Copperfield” (with W.C. Fields as Micawber), Selznick asked Corbaley for insight into which Dickens novels are most popular after “Copperfield.” The next day, Corbaley answered with a page-long memo chock-full of opinions and advice. Although the consensus answer was “Great Expectations,” Corbaley lodged a minority report. “Certain groups of people will always do battle for their favorite novel,” she told Selznick, “but I am confident when we get the full report you will find that PICKWICK PAPERS leads the field.”

About a month later, Corbaley messaged Selznick with the results of several studies of the matter, including figures from the Los Angeles Public Library that listed “Oliver Twist,” “A Tale of Two Cities,” and “The Pickwick Papers” as running “neck and neck” for that sought-after second spot. Always thinking, she concluded her memo with a non-Dickens pitch: “May I call to your attention that a book we own is still carried as one of the most popular Period novels ever written in this country, THE CRISIS, by Winston Churchill.”

THE STORY WHISPERER

The memos that passed between Corbaley and Selznick reveal some of the frustration felt by story editors (and story analysts) then and now: Days of work might go into developing reports on potential lm material, but producers could veto a project with the flick of a wrist.

On the other hand, Corbaley’s unique partnership with Mayer — her ability to transfix him with her storytelling gifts — must have provided her with an unusual degree of job satisfaction. She was good at her job, and she knew it. In an Academy oral history, MGM publicist Robert M.W. Vogel remembered the influence Corbaley had on Mayer. “Kate would go to Louis and suggest such-and-such a story, such- and-such a picture and so on and so on, and almost automatically he would take her word for it,” Vogel said, adding that his faith in her was justified. “She had a wonderful story mind,” he said.

That mind was stopped in its tracks when Corbaley died in 1938 at the age of 60 — just a year before MGM delivered its one-two punch: “Gone with the Wind” and “The Wizard of Oz.” In a front-page story, The Los Angeles Times gave the cause of death as a “brief illness,” but her hometown paper elaborated on that account, explaining that she had been ill with a cold that progressed to a case of pneumonia. The New York Times ran an obituary, and the Associated Press put the news out on its wires.

MGM had lost an irreplaceable talent. Simply put, when Kate spoke, Louis B. listened.

“He liked the way she talked, he liked the way she thought, he liked the way she narrated,” Eyman said. “He functioned in his head to a great extent, and he could just sort of close his eyes and listen and see the film in his head as she talked the story. It determined what got bought, how much they paid, and who got cast. To a great extent, it all depended on how Kate Corbaley narrated the story.”

It’s not known whether Mayer, who could be brought to tears by Corbaley’s storytelling, wept again at her funeral service at what is now St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral in the West Adams district of Los Angeles. But according to MGM scenario department head Samuel Marx, the boss was bereft at the loss of the right-hand woman responsible for so many of his creative and business decisions.

On that most solemn of days, Mayer expressed his sentiments to Marx plainly: “I would rather have lost any star than this woman.” ■