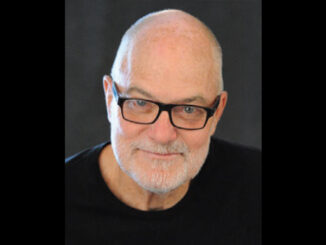

By Peter Tonguette

As one of the most admired negative cutters in Hollywood, Mo Henry made the “final cuts” on some of the most successful movies of the last four decades.

As a negative cutter, Henry was responsible for assuring that the cuts decided on by the picture editor and director in the workprint were recreated, with pinpoint accuracy, in the original camera negative. Her credits stretch as far back as Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws” (1975), her first film, and continue through Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Licorice Pizza” (2021), her last. In between, she served as negative cutter on such beloved and acclaimed movies as Richard Linklater’s “Before Sunrise” (1995), Michael Mann’s “Heat” (1995), David Lynch’s “Mulholland Drive” (2001), and, among her own favorites, the second Harry Potter movie, “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets” (2002).

Henry died on January 14 at the age of 67 in Los Angeles, where she had lived her entire life. She is remembered among her many colleagues not just for her talent and professionalism, but her dedication to her craft.

“Combining those two dangerous words ‘negative’ and ‘cutter’ to describe Mo Henry seems wrong, because she was the most ‘positive’ ‘joiner’ you would ever want to meet and work with,” said picture editor Walter Murch, ACE, who worked with Henry on several films, including “Apocalypse Now Redux” (2001).

Henry belonged to what might be considered the first family of negative cutters. One of four children born to Mike and Patricia Henry, her father was a negative cutter; her aunt—her father’s sister—was a negative cutter; and her son, Logan Henry, is a negative cutter.

Despite this heritage, Mo did not necessarily dream of a life working with reels of film. Mo just simply wanted a job, and her father was aware of an opportunity at Universal. “She moved out of her parents’ place the day she turned 18, and her dad got her a job,” Logan Henry said. “At the time, she was just young and needed something to do, but she really blossomed in the industry and she really took to it.”

In a 2015 interview with CineMontage, Henry said she was well-suited for the job. “I had the right personality and I was accurate,” she said. She began working with opticals on the 7 p.m. to 4 a.m. shift, she recalled. Then came “Jaws.” Although the film would become one of the signature blockbusters of its age, she was entrusted with negative cutting on the film because no one realized how good it was at the time. “My boss, who happened to be my dad, asked me to start on it,” she told CineMontage. “He said, ‘It looks like it’s headed straight for TV, so if you make a mistake, nobody will know.’” After the success of “Jaws,” Henry worked, often uncredited, on other major feature films, but she eventually landed at Quinn Martin Productions, which was her entrée into television programming, which she enjoyed.

After all, the difficulty of work in her profession was determined by the number of cuts she had to make, and TV shows in those days did not have an overabundance of them. “I loved cutting ‘M*A*S*H,’” she remembered to CineMontage. “It was only half an hour and the style was lots of long takes. Each reel had very few cuts, so it was fun to work on.”

‘Looks like it’s headed straight for TV,’ the boss said. It turned out to be ‘Jaws.’

In the mid-1980s, Henry took a sabbatical to pursue interior design and real estate, which had been her original aspiration. After a while, though, she felt compelled to return to filmmaking. She went to work for a commercial production company, first as a P.A. and then as a production coordinator, and eventually resumed her career as a negative cutter at Universal.

Following numerous entreaties, legendary negative cutter Donah Bassett persuaded Henry to work for her company. “From then on, I cut features exclusively,” Henry told CineMontage. “I had never had to deal with things like multiple-language soundtracks, multiple elements like interpositives, internegatives, and overlays.” Yet Henry absorbed it all, and Bassett eventually asked her to take over the company. She bought the company in 1995.

Although Henry enjoyed negative cutting as a craft, she relished running her own business, which was known, for the entirety of its existence, as D. Bassett & Associates. Henry nurtured relationships with executives and won contracts from major studios; Warner Bros. was among her company’s biggest clients during the peak years of the mid-to-late 1990s. “As a business-owner, she really hit her stride and just had a pretty well-oiled post-production machine,” Logan Henry said. “Those were the busiest years, and really a boom for her business.” High-profile productions from those days include everything from “Batman Forever” (1995) to “Twister” (1996), “Air Force One” (1997) to “Lethal Weapon 4” (1998).

At its peak, D. Bassett & Associates did the negative-cutting on about 30 titles annually—with as many as four or five being worked on concurrently—and employed as many as eight full-time negative-cutters, Logan Henry said. “She became a very, very skilled cutter,” he said. “She had a very strong reputation for just not making mistakes.”

Her rule for her employees was: one missed cut on a project would be over-looked, but a second missed cut meant you were out the door. “The missed cuts that any of her employees did throughout her tenure you could count on two hands,” Logan Henry said.

Among the most challenging projects of Henry’s career was “Apocalypse Now Redux,” director Francis Ford Coppola’s ambitious reediting of his 1979 Vietnam War masterpiece. “On that film, she had to take B-negative 35mm stock that had been stored for 20 years in limestone caves in Pennsylvania, and integrate it with the fragile, dirty, much-printed original negative of the 1979 ‘Apocalypse,’” Walter Murch said. “Did her hands tremble? I was not there to see her actual cutting, but I doubt it.”

In fact, Murch recalled, contact printing had rendered the first reel of “Apocalypse Now” so dirty that normal cleaning would not suffice; hand-tweezers and Q-tips did not work, either.

“Mo suggested: ‘Hot alkaline bath,’” Murch recounted. “Francis Coppola, risk-taker, was immediately interested. ‘Sounds like Medieval torture,’ he said. ‘Hot alkaline will puff up the emulsion, softening it,’ Mo explained, ‘and then we gently agitate the bath water as the film runs through the rollers, and the dirt just floats off the softened emulsion.’ ‘What’s the risk?’ wondered Francis. ‘A one-in-ten chance that the emulsion will get so soft that it unbinds from the acetate, and reel one comes out as clear leader, with the emulsion just a rainbow puddle at the bottom of the tank.’ Francis, who trusted Mo, as all of us did, said, ‘Let’s do it!’ And so it came to pass: reel one went through the hot alkaline bath and . . . emerged beautiful and clean, emulsion still bound to the acetate. To Mo, smiling and implacable, this was business as usual.”

After the digital revolution, the traditional negative-cutting business at D. Bassett & Associates slowed down, though she remained available for directors who preferred to work in film—including Paul Thomas Anderson and Christopher Nolan—as well as for archival work with studios. And, at the tail end of her career, she took on a project arguably unique in all of film history: the assembly of Orson Welles’s long-unfinished film “The Other Side of the Wind,” which was shot in the early-to-mid 1970s and finally released by Netflix in 2018.

“I don’t know if any other film project has been as complex—no doubt one of the reasons that Orson was unable to finish the movie,” said picture editor Bob Murawski, noting that the film had been shot in 35mm, 16mm, Super 8, color, black-and-white, and other formats. “And much of it had been cut up into tiny pieces many decades before we ever got involved. Mo fearlessly took on the almost impossible task of organizing and reassembling all of it, a meticulous process that consumed many months before I started, and continued all the way through our editing process. It is safe to say that Orson’s movie could not have been finished without the mighty work of Mo Henry.”

Mo Henry looked back on her life and accomplishments with satisfaction.

“The experiences she had and the relationships she built over the years was because of her work,” Logan Henry said. “She certainly didn’t have an ego about it at all, but she was grateful for what the business gave her throughout her life.”