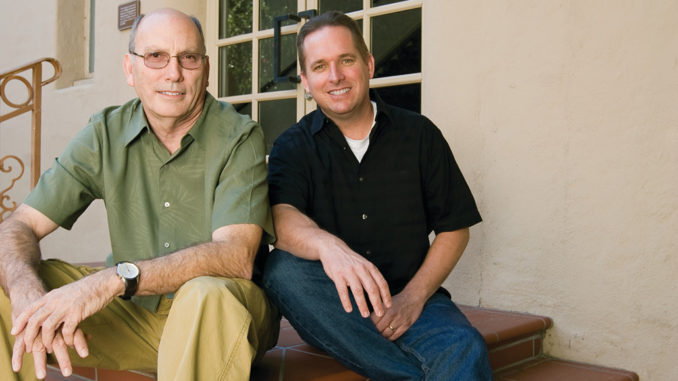

by Michael Kunkes • photo by Wm. Stetz

French composer Maurice Ravel said, “We should always remember that sensitiveness and emotion constitute the real content of a work of art.” Few words better express the filmmaking vision of iconic actor, director, producer and composer Clint Eastwood, a vision that is realized in no small part by Eastwood’s picture editors––Oscar winner Joel Cox, A.C.E., and Gary Roach. In 2008, the three partnered on a pair of deeply affecting emotional dramas––Universal’s recent Changeling, the true account of 1920s LAPD corruption and cover-up in the case of a missing child and serial killer, and Warner Bros.’ just-released Gran Torino, which marks Eastwood’s return to acting as an iron-willed Korean War veteran, forced by changing times and immigrant neighbors to confront his own prejudices.

For Cox, Gran Torino is the 33rd collaboration in as many years with Eastwood’s Warner Bros.-based production company, Malpaso Productions––as editor, supervising editor and assistant editor––one of the most prolific creative alliances in Hollywood history. Cox grew up at Warner, starting in the mailroom in 1961; he’s been working in Hollywood since appearing onscreen as a baby in 1942’s Random Harvest. Cox learned to cut by watching and being mentored by legendary editors such as Ralph E. Winters, Sam O’Steen, Walter Thompson and Bill Ziegler. He was already a battle-tested assistant editor when he came to work for Malpaso in 1976––and almost immediately found himself co-editing Eastwood-directed and -acted films with another leading editor and mentor, the late Ferris Webster. The rewards have been many for Cox, including a 1993 Oscar for Best Film Editing of Unforgiven, and a second nomination for Million Dollar Baby in 2004.

Roach joined Malpaso as a young apprentice editor in 1996. While working on Absolute Power (1997), he was in an advanced state of on-the-job training, learning the Avid from assistant editor Tony Bozanich and film assembly from Cox and his longtime assistant, Michael Cipriano. Within a year, Roach became a full assistant on the Eastwood-directed Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and, in a sharing rather than passing of the torch, became Cox’s co-editor in 2006.

CineMontage sat down with the two collaborators at Cox’s cutting room at Malpaso on the Warner lot as they were finishing post-production on Gran Torino.

CineMontage: How did you get your big breaks?

Joel Cox: When I went to work for Clint in 1976, I had just one editing credit, Farewell My Lovely (1975), which I co-edited with Walter Thompson. That year, I took over the final editing of The Outlaw Josey Wales when Ferris Webster, Clint’s regular editor, became ill. That’s how my relationship with Clint came together. I co-edited with Ferris until he retired after Honkytonk Man in 1982, and the next year, I took over the reins as Clint’s sole editor on Sudden Impact.

Gary Roach: For years, Clint would ask me if I was cutting any scenes, but I was too busy with assistant work. My break came in 2006 when he decided to start shooting Letters from Iwo Jima at the same time Joel was editing Flags of Our Fathers, and Clint really wanted me to co-edit Letters. So I’m thinking, “Great; the first film I edit is going to be in Japanese.” I remember asking Clint if Joel and I would have an interpreter in the cutting room and he said, “Nope. You guys will figure it out.”

CM: Joel, how have you passed along what you’ve learned?

JC: The method I’ve taught Gary is the one I learned when I was an assistant. We look at dailies and when we sit down to actually edit a scene, we run each of the takes and create a page or two of handwritten notes about what is important in each take––the emotions, the feelings, the looks on the characters’ faces, their actions, shot angles, take numbers––and write all that down as a bible that gives us the direction of that scene.

CM: Gary, what is the toughest adjustment you’ve had to make from being an assistant?

GR: At the end of Changeling, I handled all the cutting in of visual effects shots, worked with the sound editors and kept the DI going. I got completely in the mode of handling all that technical stuff, and then had to get back into creative mode for Gran Torino. Because I’ve only done a few shows, it takes me a few days to get back into that role.

Photo by Tony Rivetti, Jr. Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures

CM: What’s the typical process of working with Clint Eastwood?

JC: We never go on location. Clint wants us here to look at the film and discuss with him what we’ve seen. Gary and I cut film during the week, then ship him what we’ve done; he’ll suggest changes, then we move on. But Clint never tells us what to cut, what scenes or angles to use. There’s a lot of responsibility––but also a lot of trust. By the time he sees a first cut, it’s already pretty close.

CM: How do you divide up scenes and sequences?

JC: It’s whoever comes in first in the morning! We don’t sit down and say, “You do this and I’ll do that.” Sometimes, there will be two or three scenes in a row that, because of the way they were shot, would work better if the same person cut them. But otherwise, that’s exactly how it works. A lot of times, you will see two editors on a film and be able to pick out the different ways they have of doing things––but Gary and I are from the same mold. You’d have to be me to know who cut which scenes.

GR: The way it worked out, we each cut almost exactly half of Changeling and Gran Torino. After ten years of sitting with this amazing editor and director, I’ve come to know Joel’s style as well as what Clint likes. I can cut a scene and he can cut the very next scene, simply because there is no method to our madness. Our styles just flow together.

CM: Does Clint make major changes?

JC: I’ve worked for Clint for over 33 years, and he has actually disassembled only one sequence on me––and that only because the actress in the scene wanted more close-ups. Clint says that if a scene works, there are no rules to follow. My only rule is that I try never to cross the imaginary 180-degree line when there are two people in a scene, because I don’t like to see them both looking in the same direction; for example, both looking camera right. I really feel that the audience should see two people looking at each other.

CM: Speaking of twos, it seems that many of the best moments in Eastwood films are two-shots.

JC: The way we edit, we don’t go to a lot of close-ups––which makes it tougher because as editors we’re worried about matching. But Clint won’t inhibit an actor for the sake of matching shots. He wants a 40-foot screen utilized across 40 feet, so very rarely will you see a very extreme close-up with Clint, and then only for a very good reason. For him, the emotion of the scene might be in the wider shot because you have the character’s whole body language giving you the emotion; it’s not just in the eyes.

CM: How much of Changeling did not make the final cut?

GR: Our first cut was 3:15, and we ultimately got it down to 2:20 by cutting sequences that took the story into areas it didn’t need to go. When the Mounties come to arrest Northcott [Jason Butler Harner], Clint shot a long sequence in which he temporarily eludes capture in a rooftop chase. Then we were into a chase movie and Changeling was not about that. Another plot line that was removed was a sequence that takes place when Christine [Angelina Jolie] comes home from the mental institution and Gustav Briegleb [John Malkovich] brings men to the house to protect her because he thought she was in danger from the LAPD.

JC: Clint looks at the big picture and says, “This scene takes us away from moving the picture along, so we have to cut it.” And even when he’s acting in one of his own films, he’s not afraid to cut himself out.

“Neither Clint nor I quite get what people who shoot a million feet do with all that film. You burden the actors down, you burden their performances. His actors come to the set well rehearsed and knowing his method. He believes that there’s freshness in the first take of a performance that you lose five to 20 takes down the road.” – Joel Cox

CM: How did Gran Torino come to your attention?

JC: Gary and I were editing Changeling in Carmel, near where Clint lives, when he brought us the script for Gran Torino. We both read it and I told Clint, “It’s almost as if this guy [Nick Schenk] wrote it for you.” He thought it was kind of off-the-wall and didn’t really know how people would react to it. I told him, “People have to understand that you’re just playing a character; this isn’t really who you are.” And the truth is, though people may think of him as Dirty Harry, he’s more like the Robert Kincaid character in Bridges of Madison County––very soft-hearted and easygoing.

CM: How would you describe Gran Torino?

JC: Gran Torino is a smaller, more intimate film than some of Clint’s more recent movies. I would describe it as “Grumpy Old Men meets Archie Bunker meets Dirty Harry.” Also, like Million Dollar Baby, it has a plot twist that you will never see coming.

CM: What was the most challenging scene for you to cut––in either movie?

JC: In Changeling, there’s the hearing scene at the institution between Christine and Dr. Steele [Denis O’Hare]. He’s sitting at his desk, looking over his notes and humming. She thinks he’s going to release her, when actually he’s getting ready to completely take her apart. Editing that scene was all about tempo, timing and holding the cuts. Music also plays a part in the hanging scene at San Quentin at the end of the film. Northcott is singing “Silent Night” on the gallows, and as he sings the words “…mother and child,” the trap opens––I cut quickly to Christine then back to him and down he went. You take a moment like that, set it up and put it into position to play a certain way. These are the little things an editor does that don’t jump out at you.

GR: In Gran Torino, there’s a great scene in the barbershop where Clint and the barber try to teach Thao [Bee Vang], the Hmong teen, how to banter back and forth with people like “real men.” It was not an easy scene because there was just so much dialogue and I wanted to create pauses that would allow the right emotional tone into the scene. What Clint did with the Hmong actors was amazing. They surround his character throughout the film and he got great performances out of these amateur actors with little or no previous experience.

There is also the scene in Changeling where Sanford [Eddie Alderson] is in the police station and another kid is sitting there tapping a ruler on his shoulder, intercut with the scene at the Wineville ranch where Northcott is chopping up a kid. We don’t normally do a lot of quick cutting, but I felt we needed to do these one-second cuts of the axe coming down, cutting to the ruler tapping on the kid’s shoulder, then to the kid’s eyes. I also did some variable speeds of the axe coming down in the Avid. I had no idea what Clint was going to say, and when he saw it, he just said, “Hmmm, yeah,” and walked out of the room. And I thought, “Oh, that’s just great.” And the next day he came in and said, “No, I like it––I just had to sleep on it.”

“Clint will have a tune in mind, and he’ll sit down at the piano and plunk it out… They’ll bring a bunch of material to us, we load it in, and then Joel will overlay and work these themes together to put together a score that Clint invariably falls in love with.” – Gary Roach

CM: Was there any point where you were editing Changeling and Gran Torino at the same time?

JC: Changeling was basically finished when we started editing Gran Torino, to the point where we were able to take it to Cannes and run it.

GR: We had a cut of Changeling within a week of the wrap, and on Gran Torino, we were virtually up to camera the entire time, with a cut two days after production wrapped. At Warner Bros., Joel and I have separate editing rooms. But when we go up to Carmel, we have two Avids in the same room, and Clint will sit between us, watch what we’re doing and give us the changes he wants us to make. We get things done really quickly.

CM: Joel, would you ever edit film again?

JC: I could do it, but a lot of editors today don’t have the training and background to work with film anymore. The Avid is a revolutionary tool, but I edit electronically the same way I cut on the Moviola. I do the mark-in, get to the end of the shot, do my mark-out and cut that in. I’ve had young editors tell me that they spend 90 percent of their time in edit mode sliding the cuts. I only do that after I’ve put four or five cuts together and run the scene. If there’s something I want to adjust then, I will––but I don’t even spend ten percent of my time sliding cuts.

CM: Does Clint shoot a lot of footage?

JC: Neither Clint nor I quite get what people who shoot a million feet do with all that film. You burden the actors down, you burden their performances. His actors come to the set well rehearsed and knowing his method. He believes that there’s freshness in the first take of a performance that you lose five to 20 takes down the road. He’s not against a stutter or a flaw in a reading. That’s why Clint doesn’t like to loop. You can’t re-create the ambient sound or the voice inflections and emotion that you get on the set. He’d rather have the performance. But he always gives me more than an adequate amount of footage to edit the film.

CM: How do you work with music?

JC: Clint and I both believe that music is something that is there to support the film, not to be a character. We also believe that you don’t have to play music from the first frame till the last; that’s not the style of movie he does. If you have to use music to get people to feel strong emotions, then the film isn’t working by itself. He knows his audience; he’s making films for adults.

GR: Clint will have a tune in mind, and he’ll sit down at the piano and plunk it out, and somewhere along the way he’ll get together with his son Kyle and arranger Michael Stevens. They’ll bring a bunch of material to us, we load it in, and then Joel will overlay and work these themes together to put together a score that Clint invariably falls in love with. At the very end, Lennie Niehaus, Clint’s orchestrator, comes in and writes string and other arrangements that fill it all out.

CM: What’s up next for you two?

JC: The Human Factor, which Clint starts shooting in March. Morgan Freeman will be portraying Nelson Mandela during his first term as President of South Africa, after the fall of apartheid.

CM: Where do you think picture editing today is heading?

JC: The one thing I fear is that films today are being made for a much younger audience and edited in a very different style. I am not against that. However, I think a film is viewed through the eyes of the characters, and I don’t want to tip the audience off to something that’s going to happen before the characters see it. It should be like a book; you never know until you turn the page. The audience should be like a fly on the wall. It’s the characters’ story, not the audience’s.

GR: This is why it’s important for me to have a similar style to Joel––so that we share the same rhythms. I must say here that Joel has been incredibly gracious in allowing me to work by his side. It’s been an incredible experience and it is so appreciated.

JC: I like to tell people we are the “masters of emotion,” because that’s what Clint’s films are all about. We don’t have egos because the films say it all. There’s huge art being created in this room, and we are the luckiest guys in the world.