by Peter Flood

I am a war baby who grew up in Texas before leaving for a larger world that included living in Manhattan for 22 years and moving to Los Angeles to work as a story analyst. So, if what I have to say now reads old to anyone, well good — because old has a way of becoming new again, especially when old is as unforgettable as My Darling Clementine.

Don’t believe me? Then Google “Metropolitan Museum of Art” and run a search on “Cycladic” and tell me how old it looks to you. Or visit the medieval refectory in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan to see da Vinci’s The Last Supper; not the photo, the real thing. There are two images inside on opposite walls; One is the real thing, the other decorative. I have nothing against decorative, but the real thing takes you beyond what you think you already know.

I’m not a hero, but I know what one looks like thanks in part to My Darling Clementine.

Art in the form of talking pictures, for example, looks at the world in a way that can trip us forward into a feeling-based understanding of who we are or want to be in this world. This understanding may come in an instant or slowly, learned over time through an accumulation of instants. But, once it arrives, it is irrevocable: I do what I see to do, or I don’t.

One of the better angels of age is patience when it comes to both storytelling and sex, a learned appreciation for the inevitable in a narrative sense. Patience knows the value of endurance, and endurance is heroic, I have come to believe. I’m not a hero, but I know what one looks like thanks in part to My Darling Clementine.

I was too young to see this movie when it was first released in 1946, so what I have to say now is less about love at first sight than my slow realization of a baseline meaning of the word “good.” Writing coverage on-lot and off, I keep a post-it reminder on every computer to ask myself the question: “Is it good?” And by “good” I don’t mean goody-goody, well crafted or cool. I mean “good” in the Aristotelian sense of “adding to existence,” as opposed to diminishing existence for no purpose other than cruelty disguised as entertainment. So in other words, what’s the point?

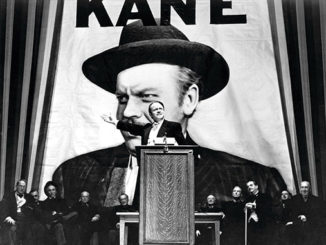

The point is this: What makes us want to see something again? What is good in My Darling Clementine is not historical accuracy about a 30-second gunfight. The title character is a familiar fiction, the Earps were never cowboys, Tombstone is in monotonous southern Arizona and not Monument Valley, Doc Holliday was a dentist and not a surgeon, and he didn’t die at the OK Corral.

The good in My Darling Clementine is poetry, not fact. The good is director John Ford’s humanist and artful approach to character and pace. Also his painterly vision of the world with a deep-focus, da Vinci-like sense of composition, a parade of images that generate emotion deeper than stimulation. At the center of this vision are people who feel “ordinary,” characters who deliver the humanity of everyday heroism. There is no superhero invincibility, no guarantee of safety or even a good outcome in life other than what you bring with you: courage, discernment, self-reliance and restraint.

Restraint is what I see in the Henry Fonda characterization of Wyatt Earp as a man attentive to and more respectful of others than threatening. Slow to anger, you might say, and it’s a value that generally disappeared from storytelling during the 1990s on the assumption that it requires too much of us to wait long enough to know what the fight is and why it’s necessary — “necessary” being the key word here.

“Necessary” makes My Darling Clementine a morality play. The fight is neither desired nor avoided; it comes to the Fonda character like it comes to a first responder who does what has to be done. The same can be said for other great Western heroes: Ethan Edwards in The Searchers for example, or…for my own father. Real heroes work, prosper, care for children and aging parents, cook, clean, drive, play games, tell jokes, go to war and die suddenly.

The point is that I have learned from watching heroes in life, and as images that represent what life can be in worlds other than my own; worlds in which “adding to existence” is artfully distinguished from selfishness, ignorance and neglect. It’s not a judgmental thing, but an observation of responsibility, to ourselves and to others. Responsibility is the real thing I see in My Darling Clementine and other, character-driven, talking-picture art.