By Rick Mitchell

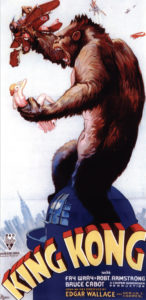

The commencement of production on Peter Jackson’s remake of King Kong calls for a look back at the 1933 original, a pioneering film in many ways, including post production.

Unfortunately, except for visual and sound effects, there has been very little documentation of this aspect of the original film. However, it originated procedures and techniques that would be used until supplanted a decade ago by the digital technology that will be central to the execution of Jackson’s 21st century version.

Released four and a half years after the introduction of sound, Kong can actually be seen as representing the industry’s ultimate triumph over the new technology, a perfect merging of the visual art that silent film had become, especially in its last four years, with the aesthetic possibilities of the aural.

The film begins with a series of dialogue scenes staged and shot in a style reminiscent of the earliest talking pictures. As it moves away from New York, dialogue decreases and the visuals are accentuated, especially after the introduction of the musical score in Reel 2B, culminating in an entire central reel (4B) carried solely by the visuals, sound effects and music.

The original Kong was made by RKO Radio Pictures, the first major company formed specifically for the making of sound films. It was also the result of RCA’s David Sarnoff’s desire to get in on the new phenomenon. In 1928, RCA purchased the FBO Studios at Melrose and Gower in Hollywood, and later the Pathe lot in Culver City, on whose then Stage 11 the jungle scenes for Kong and the concurrent The Most Dangerous Game would be shot.

According to an International Photographer article published in fall 1929, by then RKO’s editing rooms were set up with the basic equipment that mostly would be standard in the industry for the next 65 years: editing machines, sync blocks, splicers and coding machines. Though Kevin Brownlow’s interviews for The Parade’s Gone By revealed that few editors of silent films used viewing devices, sound required them. RKO had Moviolas with heads for reading optical tracks, as well as separate optical track readers for the assistant(s).

The editorial staff consisted of the editor, at least one assistant, and one or two apprentices. Unfortunately, little is known about the picture editorial staff of Kong. As with all other departments in the studio system, editorial crews were assigned by the department head unless producers or directors requested specific editors. It’s not known if Ted Cheesman was assigned to Kong or requested it, but he would edit all of Merian C. Cooper’s subsequent productions at RKO, including She (1935) and Mighty Joe Young (1949). His assistant(s) and apprentice(s) have not been identified to this date.

The daily routine of the editing room was basically the same as 60 years later. As the sound was recorded optically on 35mm negative, the editing room would receive both daily picture and track from the lab, CFI, and it would be logged, synced, screened, ink coded and broken down for editing. Prior to the adoption of splicing tape in the mid-1950s, the editor would make physical cuts on both picture and track with scissors, paperclip the ends together, and wind the footage onto a takeup reel.

The assistant or apprentice would subsequently hot splice this material. Of course, a frame was lost on each side of the cut, and if a scene had to be extended, it was filled out with black leader until a reprint could be ordered.

This is one reason why many older editors’ first cuts were rough. They prided themselves on how few black frames were in their cuts or in having a low number of reprint orders. Yet this did not prevent fast paced editing, as many scenes in Kong will attest (The last editor to use hot splicing was Richard G. Wray, A.C.E., the brother of the late Kong star Fay Wray. Up until his retirement in the mid-1970s, when he was working on Marcus Welby, M.D. at Universal, Wray’s first cut picture would be hot spliced, but changes were made with adhesive tape.).

One unusual aspect of the production of Kong is that, in those pre-union days, it was shot off and on for over a year. Scenes requiring rear projected stop-motion material would be held up until the animation was done. Fay Wray made at least three films, the concurrently shot The Most Dangerous Game, Doctor X and Mystery Of The Wax Museum, during Kong’s production. It’s not known what affect this had on the editing room; was the crew laid off or did they work on other pictures when they had nothing to do? It’s also not clear what was done about incorporating effects shots into the work picture. Whereas in previous films involving extensive visual effects, such scenes were usually clustered into one or two sequences. Kong, its sequel Son Of Kong and Universal’s The Invisible Man were the first films to have large numbers of such shots spread throughout their entirety.

The unique post-production requirements of King Kong would become absorbed into the standard techniques of the industry.

With two of the processes used in Kong – the Dunning Traveling Matte Process and rear projection – finished composites would be part of regular dailies. Only those shots using the Frank Williams Traveling Matte Process and those involving matte paintings would involve waiting for compositing. It’s also not known whether or not the Kong editing room got pre-opts to work with.

In the Dunning Process, invented in 1928 by C. Dodge Dunning, a 17- year-old high schooler, the background was shot first and a print from it, dyed yellow, would be bipacked in the production camera with an unexposed pan-chromatic negative. The foreground would be staged in front of a blue backing and illuminated with yellow light. This allowed it to print through the yellow dyed background, while the blue backing caused the background to be exposed in all other areas. As confusing as this sounds, the process worked quite well and was used for most composite photography until the perfection of rear projection. One scene in Kong is specifically identified as being a Dunning shot: Kong shaking the sailors off the log. All of the composites in The Most Dangerous Game were done by the Dunning Process as well.

The drawback to the Dunning Process was that interaction between the foreground and background was difficult. According to visual effects artist Jim Danforth, to do such shots for Kong by it, a Moviola was linked to the camera by the same techniques used to link the sound recorder so that another print of the background plate could be viewed in sync with the one bipacked in the camera.

Other composite shots were done by the Frank Williams Process, the industry’s first perfected double-matting system. Here, the foreground was photographed, initially against either black velvet or a pure white backing. But, by the time of Kong, it was shot against a blue backing and with bipacked blue sensitive and a panchromatic negative. Prints from these negatives would produce the male and female mattes, and everything would then be combined in an optical printer. Additionally, Williams developed a live action variation of the rotoscoping technique developed by Max Fleischer to combine live action and cartoons, in which the scene in question is projected frame-by-frame onto animation cels, the area to be matted inked in, and the cels then photographed to create the matte. It’s not certain if this latter technique was used anywhere in Kong, though it is used in She and became a key component in Universal’s visual effects pallet, and not just in the Invisible Man films and Abbott and Costello comedies. It’s not known if the Kong Editorial staff was involved in lining up the foreground and background elements of these shots as some editors or assistants would be called on to do in later years, or if this was done by the optical house, as is standard today.

The daily routine of the editing room was basically the same as 60 years later.

Pioneering sound effects editor/designer Murray Spivack initially worked from the script in determining what sounds he needed for Kong, the dinosaurs and other effects, a technique used later by studio staff editors when brought on in advance for pictures with unique sound needs. It’s not known at what point he began specifically fitting these sounds to the picture or what he worked with in doing so. (By the early ’40s, dupe negatives were made on positive stock and prints from them provided to sound and music editors and for dubbing room projection. It’s not clear how early this process was introduced or what was done before then.) To minimize the deterioration of sound quality, until the late 1930s (and even after in some instances) only those scenes involving the addition of sound effects and music would be re-recorded.

Otherwise, the original production sound negative would be cut like that of the picture; sound splices are quite audible when these tracks are played on modern equipment.

Kong apparently was not publicly previewed, but was shown to RKO executives in an approximately two-hour version before being locked at a tight 100 minutes on 11 1,000 ft. reels by late January 1933. At least a month would be required for dubbing, negative cutting, timing and the striking of the initial prints needed for show exhibitors and the premiere engagements at the Radio City Music Hall and Roxy in New York and Grauman’s Chinese in Hollywood.

The unique post-production requirements of King Kong would become absorbed into the standard techniques of the industry, improved upon slowly by new technologies until the introduction of digital processes in the 1990s. Much of the research and development in this area has been done over the last decade, but this doesn’t mean Peter Jackson and his staff will have an easier time than 70 years ago.