by Kevin Lewis

During the Golden Age of Hollywood, Louis B. Mayer, Darryl F. Zanuck and Cecil B. De Mille were powerful enough to determine who would work in the American film industry. The old cliché that behind every great man is a woman definitely applied to these three producers. If Mayer, Zanuck and De Mille––three very tough-minded, dominating men––shared one trait in common, it was a reliance on the judgment of the women around them. Zanuck’s wife Virginia guided him throughout his life, just as Ida Koverman, Mayer’s secretary/majordomo, directed him. Mayer’s confidence in women even transferred to his daughters, Edith Goetz and Irene Mayer Selznick, both powerful creative women who guided their husbands. DeMille’s female creative team, which included his wife Constance and scenarist Jeanie Macpherson, was humorously regarded as his harem.

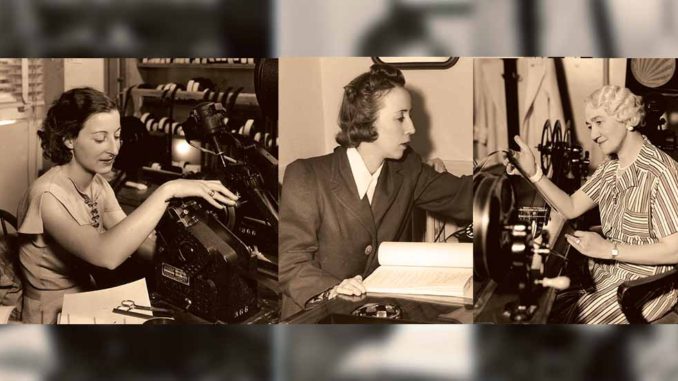

Three women editors from the 1920s through the 1950s had constant access to each of these men, respectively: Margaret Booth with Mayer at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Barbara McLean with Zanuck at 20th Century-Fox Film Studios and Anne Bauchens with DeMille at Paramount Pictures. Though Bauchens never held an administrative post at the studio like Booth and McLean eventually did, she was the film editor of the chief money-maker on the lot, De Mille. Together, Booth, McLean and Bauchens represented three of only eight female film editors working in Hollywood in the 1930s.

Of the three women, Booth had the most pervasive influence throughout the industry. Long after Mayer left MGM in 1951, she continued as supervising editor until 1968 when she was 70 years old. Then Ray Stark hired her as his supervising editor until 1982. In many respects, the politically astute Booth became the doyenne of the film industry, one of the few crossovers between the old and new Hollywood.

Unlike Booth, McLean was too shy to involve herself with industry politics, but firmly held the editorial department in her grasp through sheer personal determination and an enviable professional record. Bauchens never really emerged from the De Mille persona to establish herself as a versatile editor. Though it could be argued that the annual De Mille spectacles kept the financially unstable Paramount afloat, Doane Harrison became the studio’s editor who was promoted to an assistant producer.

Margaret Booth (1898-2002)

Margaret Booth was born in the 19th century and lived until the 21th century. Her career began with D.W. Griffith and ended with Neil Simon, almost 65 years later. During that period, she was supervising editor at MGM from 1939 through 1968, which was almost the end of the run for the old studio. When she was in her 70s, producer Ray Stark hired her to be his supervising editor for such productions as the Barbra Streisand vehicles The Way We Were (1973) and Funny Lady (1975). She also served as an associate producer for Stark through 1985 with The Sluggers Wife.

Booth was so respected in the industry that, in 1977, when Film Comment asked 100 film editors to name the top ten editors in the history of the medium, she placed number three in the poll. And why not? She was still at the top of her game after half a century––and still had nearly a decade of work left in her. Booth was always an MGM woman, however, as evidenced by her selection of three MGM classics as her favorite editing jobs: Bombshell (1933), Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) and Camille (1937). She was reticent about personal publicity and the literature about her life is meager. Toward the end of her MGM tenure, she consented to an interview with film historian/filmmaker Kevin Brownlow for his landmark oral history book, The Parade’s Gone By, when she was in London in 1965.

Booth (whose brother Elmer Booth was an actor in Griffith’s films until he was killed in a road accident in 1915) was a patcher/film joiner/negative cutter with the D.W. Griffith company around 1920. Within a few years, she was working on the films of John M. Stahl at Louis B. Mayer Productions on Mission Road in Eastlake Park, then just outside of Los Angeles proper. Stahl encouraged her to watch him edit his own dailies. “That way, he taught me the dramatic values of cutting; in fact, he taught me how to edit,” she told Brownlow.

When Mayer’s studio was acquired by Marcus Loew of Loew’s, Inc. to form Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1924, Booth found her niche. She became an editor in 1924 when Stahl was impressed with her editing of outtakes. “After a while, he started to look at these efforts of mine, and sometimes he’d take a whole sequence that I had cut and put it in the picture,” she recalled. “Then, gradually, I got around to making his first cut––and that’s how I got to be an editor.”

“Time and again, editors were sent back to their cutting rooms to adjust their work to her liking. But [Margaret Booth] was consistent and fair, and appreciated both good work and good effort.” – Ralph E. Winters

But her loyalty was to MGM, not to Stahl, and she refused to join him when he moved to Tiffany-Stahl and then Universal Pictures. As she told Brownlow, she never wanted to leave MGM and, “I didn’t want to work for just one man; I enjoyed working for everyone.” Micromanager Mayer, who was suspicious of stars, directors and screenwriters, made Booth his decision-maker and ally, perhaps because he could truly control film content with an editor. This was a tightrope for her because, as she admitted, she mainly worked for Irving Thalberg, “the greatest man who was ever in pictures,” but who threatened Mayer’s supre-macy with Nicholas Schenck, the head of Loew’s. In any case, by 1936, Thalberg was dead and Mayer had her all to himself.

Booth did not remain loyal to the past, however, and welcomed the new editing techniques of the 1960s. “When I cut silent films, I used to count to get the rhythm,” she said in The Parade’s Gone By. “If I was cutting a march of soldiers, or anything with a beat to it, and I wanted to change the angle, I would count, ‘one-two-three-four-five-six.’ I made a beat for myself. That’s how I did it when I was cutting the film in the hand. When Moviolas came in, you could count that way too; you watched the rhythm through the glass…

“There has been no advance in technique since the silent days––except for one thing: They’re doing away with fades and dissolves,” she continued. “I like this much better than the old technique of lap dissolves, which slowed down the pace. There was a time when we made eight-to-ten-foot dissolves. We taught the audience for many years to recognize a time lapse through a lap dissolve. Now they’re educating them to direct cuts––a new technique brought about by a new generation of directors who can’t afford dissolves or fades. And I think it’s very good.”

Booth reiterated her ideas about rhythmic qualities of editing in Film Comment in 1977: “Rhythm counts so much; the pauses count so much. It’s the same as when people speak or dance––you can tell right away when it’s wrong. Everything has to be rhythmic.”

Margaret Booth was born in the 19th century and lived until the 21th century. Her career began with D.W. Griffith and ended with Neil Simon

When he was starting out in the business, the late editor Ralph E. Winters , ACE worked at the foot of the Mistress. In the obituary/tribute he wrote for her in the JAN-FEB 03 edition of Editors Guild Magazine, Winters recalled, “My first picture with ‘Miss Booth,’ as she was called, and my first assignment as an editor, was Mr. & Mrs. North, starring Gracie Allen. [Booth] was a tough taskmaster and used to drag me over the coals every day––but I learned. Eventually, I worked my way up to become one of her favorite editors and, more important to me, a close personal friend.”

According to Winters, every MGM editor was required to bring his or her work to Booth, as supervising editor. “She had her own projection room and saw all the rushes and cuts for every MGM film. She was empowered to make changes and present the editing of sequences to various producers and directors as she saw fit,” Winters wrote. “[Booth] reported directly to Mayer, a fact that some didn’t like, but there was nothing they could do about it.”

He went on to write that Booth demanded only the best from the people she supervised: “Time and again, editors were sent back to their cutting rooms to adjust their work to her liking. But she was consistent and fair, and appreciated both good work and good effort.”

One of the many things Winters learned from her was to always “keep the story in mind. She hated editing for the sake of editing––but if you had to make a bad edit to advance the story, that was fine with her. She was not afraid to go to the mat with anyone, and producers and directors alike felt her wrath when she thought that they were going in the wrong direction. She fought hard for what she believed––and she was usually right. But she always protected her editors.”

Although she was nominated for editing Mutiny on the Bounty in 1935, Booth would have to wait until the 50th annual Academy Awards ceremony in 1978 (recognizing the films of 1977) to receive her only Oscar, an Honorary Academy Award for her contributions to the art of editing, when she was 80 years old. It was a long overdue recognition from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Women in Film also awarded Booth its prestigious Crystal Award in 1983, and the American Cinema Editors (ACE) bestowed her with a Career Achievement Award in 1990. At its Board of Directors Installation Dinner in 1998, the Editors Guild presented Booth with a commemorative crystal award in celebration of her 100th birthday and her outstanding career as an editor. She died in 2002 at the age of 104.

Barbara McLean (1903-1996)

Barbara “Bobby” McLean began her career as a negative cutter for the director Rex Ingram in the early 1920s. As Barbara Pollut (she eventually married soundman Gordon McLean, presumably sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s), she worked for Ingram’s film editor, Grant Whytock, and his wife, Leotta, who was also a negative cutter. Her work on such exotic Ingram films for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as Mare Nostrum (1924) and The Garden of Allah (1927) would prepare her for the sleek adventure sagas directed by Henry King at Fox several years later. When Whytock became Samuel Goldwyn’s editor in the late 1920s, McLean followed him as his assistant and worked on films produced by Goldwyn as well as Mary Pickford, both of whom were partners in the recently formed United Artists.

Darryl F. Zanuck, co-founder and head of Twentieth Century Pictures, whose films were released through United Artists, was said to have admired a film––possibly Frank Borzage’s Secrets (1933)––on which McLean assisted. He reportedly referred to her as “one of the best editors in town” and hired her as an editor for such Twentieth Century releases The Bowery (1933) and Gallant Lady (1934), the latter for which she received her first sole editing credit.

When Zanuck and Joseph Schenck bought the Fox Pictures studio in 1935––and merged his company with it to form 20th Century-Fox––he built a true state-of-the-art, three-story editing building. No one but editors were allowed on the second floor. Screenings were arranged on the first floor and producers, rather than directors, made the editing decisions. The third floor was for film storage.

Zanuck, who was probably one of the most well-rounded film producers and executives in the industry, knew as much about editing and screenplays from his previous years as an executive with Warner Bros. as leading editors and playwrights did. Besides McLean, his two other trusted confidants were screenwriters Nunnally Johnson and Philip Dunne, both of whom he elevated to producer/directors.

McLean and her second husband, Robert Webb, who she married in 1951, were an Oscar couple. Webb directed mainly action pictures for 20th Century-Fox such as Beneath the 12-Mile Reef (1954) and Elvis Presley’s debut Love Me Tender (1956), and won his Academy Award as assistant director of King’s In Old Chicago (1937), a film edited by McLean but for which she received no nomination. A measure of Zanuck’s respect for McLean is the fact that he only assigned her to the prestige dramatic productions. The studio chief’s favorite director after John Ford was King––and McLean edited the bulk of the prolific director’s films at Fox, including Wilson (1944), for which she received an Oscar.

Darryl F. Zanuck, co-founder and head of Twentieth Century Pictures reportedly referred to Barbara McLean as “one of the best editors in town.”

Ironically, although McLean was nominated for the Academy Award six additional times, she was not nominated for editing The Robe (1953), the inaugural film shot and released in Cinemascope. The challenges involved in determining editing cuts in the widescreen process for the first time certainly seemed to deserve a special award. Her nominations include: Les Miserables (1935), Lloyds of London (1936), Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938), The Rains Came (1939) The Song of Bernadette (1943) and All About Eve (1950).

In 1949, McLean was appointed chief of the editing division at Fox, a distinction she held until 1969 when she retired. Her departure from Fox coincided roughly with Margaret Booth’s from MGM, but for different reasons. McLean retired from the studio because Webb was very ill.

When she was asked by Film Comment in 1977 to answer three questions, she was succinct, almost too much so, in her answers: What is editing? “Film editing is telling the story with film.” What is good film editing? “Good film editing is selecting the best of the film.” What is great film editing? “Great film editing occurs when you begin with great pictures.”

McLean died in 1996 from complications of Alzheimer’s Disease. Her surviving colleagues at Fox remember her as a dedicated editor who rarely socialized, not even in the studio commissary, but who interacted in truly supportive ways with her editors on other films.

Anne Bauchens (1882-1967)

Anne Bauchens probably owed her longevity in the industry as much to her slavish devotion as to her editing skills. Long before the term auteur was applied to a film director, Cecil B. De Mille was one. He was even his own film editor in the silent era, though Bauchens was his negative cutter and served as a co-editor beginning with Carmen in 1915, his third year as a director.

The cinematographer Charles Rosher related to Kevin Brownlow (for the book The Parade’s Gone By) an incident that demonstrates Bauchens’ deference to the director, which may have originated the famous line, “Ready when you are, C.B.” As Rosher, a cameraman on Carmen, recalled, “De Mille was tough on lunch breaks. One day, about 3:00 p.m., he asked, ‘Anyone hungry?’ ‘We’re not, if you’re not, chief,’ Anne Bauchens, his cutter and script girl, replied. “I yelled, ‘Speak for yourself, Anne!’ De Mille called lunch.”

The St. Louis, Missouri-born aspiring actress met De Mille while she was working for his brother, William de Mille, as a secretary in 1912. William, who used the small “de” in his surname, the true family spelling––as opposed to the pretentious Cecil––also became a director, and Bauchens even edited two of his films: Craig’s Wife (1928) and This Mad World (1931). Bauchens obviously thought the “Big D” was her destiny.

Leatrice Joy, the star of the first version of The Ten Commandments (1923), among other De Mille epics, was friendly with Bauchens. The editor, she had said, “was devoted to De Mille, and he was very comfortable with her.” Since the director-producer really wanted to be his own editor, they were like duo pianists. In fact, De Mille even blocked Paramount’s efforts to hire another editor.

Although she will ever be remembered as De Mille’s editor, Bauchens also earned the distinction of being the first woman to win an Academy Award for Editing.

But this close working relationship did not bode well for Bauchens artistically, according to her contemporary, Margaret Booth, who pointed out to Brownlow in 1965, “Anne Bauchens is the oldest editor in the business. She was editing for years before I came into the business. De Mille was a bad editor, I thought, and made her look like a bad editor. I think Anne really would have been a good editor, but she had to put up with him––which was something.” That “something” determined her nickname, “Trojan Annie,” because of the prodigious work involved in editing the elaborate De Mille epics. (Brownlow also directed a documentary on the director, Cecil B. De Mille: An American Icon, for Turner Classic Movies in 2004.)

For forty years, although she was forced by MGM and Paramount to edit other films, Bauchens worked “cheek to jowl,” with De Mille, according to film historian and writer Lisa Mitchell, who was an actress in The Ten Commandments (1956). De Mille made Mitchell privy to his methodology during this award-winning, swan-song production for both the director and editor. Mitchell recalled the separation anxiety Bauchens experienced during this production; De Mille was shooting in Egypt and the raw footage was flown to Los Angeles in refrigerated containers for her to edit without him––a physically as well as emotionally difficult experience for the then-septuagenarian editor.

Although she will ever be remembered as De Mille’s editor (in fact, only 20 of the 63 films she edited were not directed or produced by him), Bauchens also earned the distinction of being the first woman to win an Academy Award for Editing. The picture was De Mille’s Northwest Mounted Police (1940). She also received Oscar nominations for three other films by the director: Cleopatra (1934), The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and The Ten Commandments (1956).

Special thanks to Kevin Brownlow, the Leatrice Gilbert Fountain and Lisa Mitchell for their advice, use of material and inside knowledge of the people involved in this story.