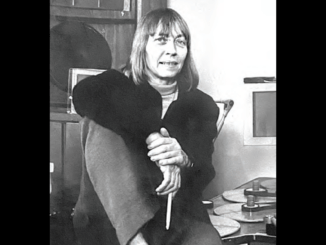

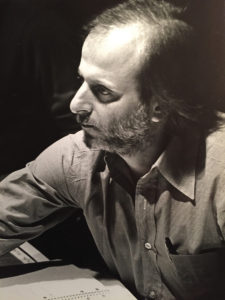

Barry Malkin, ACE

Picture Editor

October 26, 1938 – April 4, 2019

Although I was a new kid in a new neighborhood — pretty much in a new school each and every year — I do have a memory of another boy I met when I was about 14 years old. He was shooting baskets alone at the public playground near Springfield Boulevard in Queens and, seeing me watching, asked me to shoot baskets with him for 25 cents apiece. I knew I had no such skill, but was anxious to have a friend, so I took on the challenge. I lost about $1.25 in quick order, but little did I know that this boy, Barry Malkin, would remain a friend and more; he became an important professional associate throughout my life.

For a while, we knew the same kids; Barry came to my 15th birthday party (of which I actually have 8mm movies), and then we went on our separate lives. We were brought together a few years later by the film industry we had both entered through different doors.

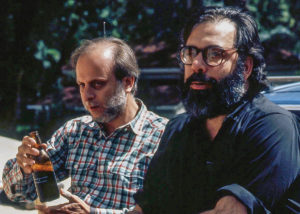

Barry had become a film editor, working with editor Aram Avakian, and I was a recent graduate of the UCLA film school who had made a film in New York edited by Avakian (You’re a Big Boy Now, 1966). So it made sense that Barry and I should work together on a new film that I planned to make while traveling across the USA. With an editing room in an RV trailer, Barry joined this cross-country adventure of The Rain People (1969), editing it as we went along our way.

It was a great adventure and was followed by a lifetime of collaboration on many movies. He was the one person from those early teenage years who was to span an entire lifetime working in film, and a collaborator on much of the work I did. Also, Barry edited many films of director friends of mine, but always remained an important and trusted collaborator throughout both of our careers.

His instincts and talent were a big influence and his skill was amazing. After the first preview of The Godfather: Part II (1974) to lackluster results in San Francisco, I made 120 changes to the film — which had to be ready in two days for another preview in San Diego. I watched as Barry executed those changes on picture and sound of a finished film (without code numbers) through the night, a feat that was essentially impossible. But Barry did it, and the subsequent San Diego preview effectively reversed that film’s fate.

His instincts and talent were a big influence and his skill was amazing. After the first preview of The Godfather: Part II (1974) to lackluster results in San Francisco, I made 120 changes to the film — which had to be ready in two days for another preview in San Diego. I watched as Barry executed those changes on picture and sound of a finished film (without code numbers) through the night, a feat that was essentially impossible. But Barry did it, and the subsequent San Diego preview effectively reversed that film’s fate.

Barry was always his own man; he never really accepted any opinion with which he didn’t personally agree and, for that reason, was a truly valuable artistic collaborator. He had his own style, his own sense of humor and his own integrity. Rarely in life nowadays do we have childhood friendships that span a lifetime — which is all the more why the passing of this dear friend and collaborator is of such importance to me.

Goodbye, dear friend, and may this rest now be as fine and complete as was the work you accomplished during your time with us.

Francis Ford Coppola

* * *

I first encountered Blackie [Malkin] at a sneak of Gordon Willis’ directorial debut, Windows in Los Angeles in 1980. I was introduced to Blackie, who quickly impressed me with his poker-faced calm, even when the film broke 10 minutes into the screening, resuming only after a half hour of rhythmic clapping and catcalls. The studio guys were ashen; Blackie showed no more emotion than a medical examiner making his rounds. For me, it was love at first sight — this was my kind of guy.

We did four movies together and he was never any different. Whether in the cutting room, the ADR studio or the final mix, he maintained an amazing professional calm and constantly balanced my mood swings. He would dampen my elation and shrug away my despair, particularly after those death marches know as “the assemblage.”

The first cut of The Freshman (1990) was particularly awful, the film lumbering by like a 200-car freight train, with Marlon Brando pausing for what seemed hours at a time. When it finally and mercifully ended, I pushed myself out of my seat at Magno’s Screening Room and just stared at Barry, waiting for his judgment, which was, “Lunch?”

He reacted no differently to more bearable first cuts, because he knew it was all a process, that the end result was miles away and there was always so much one could accomplish in post. One could not, as Lyndon Johnson famously said, “make chicken salad out of chicken shit,” but one could garnish it so it resembled something edible. And what I learned from that first cut of The Freshman, the first film we did together, was to give my scripts to Blackie months before shooting, so he could trim the fat before we rolled a foot of film. After eliminating six of the first nine scenes in The Freshman, I realized that if Blackie said, “We’ll never use it,” that meant we’d never use it, and would save days of aggravation and piles of money.

Andrew Bergman

* * *

I had the great fortune of being one of Barry’s assistant editors in the early ’80s. My older daughter once sadly remarked upon hearing about this period of my life before I had children by saying, “Wow, mom, I guess you peaked early.”

I guess she was right. Little did we know at the time, but many of us in the room tonight had the pleasure of assisting with one of the — if not the — best and most talented generation of film editors working in New York, away from the prying eyes of Hollywood studio executives, on a body of movies unparalleled in their uniqueness and artistry that will forever define a particular style and singularity of vision rarely seen in theatres today.

Barry Malkin epitomized that generation for his character, intelligence, humor, irreverence, diligence and devotion to his family, friends and fellow filmmakers — and for his steadfast refusal to give up on this city he dearly loved. He ensured that a culture of post-production continued to flourish in New York well after the demise of the institution where many of us forged those early bonds: Sound One on the seventh floor of the Brill Building.

I think it’s safe to say Barry’s influence and reach is everlasting. He has inspired several generations to try to walk in his…sneakers. I never get through a day without thinking of his editing methodology, his work ethic, his endurance at that Moviola, the jazz on the radio, the cigarette smoke, the meals at Rincon Argentina, his smile, his laugh and his memories of a past so few of us still hold in common.

Dorian Harris, ACE

* * *

What I learned from Barry at work was like taking a master class in film editing — not only its techniques, but its ethics. Barry had the strongest sense of professionalism I’ve ever witnessed. He’d get in two hours before anyone else even entered the building.

What I learned from Barry at work was like taking a master class in film editing — not only its techniques, but its ethics. Barry had the strongest sense of professionalism I’ve ever witnessed. He’d get in two hours before anyone else even entered the building.

Barry’s razor-sharp intellect was part of what allowed him to be such a good editor. He was an expert at spotting the diamond in the rough. Often when watching dailies, he would notate the things that were bad, not the things that he liked, or what the director might want to hear. He possessed the unique talent of being able to sort through large amounts of improvised material and come up with a structure that would make the scene seem scripted. He was always able to find that certain line reading, the close-up, or the well-timed gesture that would put the right cap on a scene. That was his magic touch.

Sam Adelman

* * *

I first met Barry in the Brill Building in 1980. Reagan was on the rise, hostages in Iran, Blondie on the radio. I remember he wasn’t all that keen on me at first — I was just out of college and, in spite of never having seen a Moviola, I’d been dumped in his cutting room as a favor. Of course, I was thrilled. I was working with the guy who cut The Rain People and The Godfather: Part II. It was only a matter of time before the mysteries of making movies would be revealed.

But when I look back, I realize what Barry taught me was beyond a craft; he set a bar that shaped all of us who were around him. At the time, I didn’t understand what he was offering me; I was witnessing a master class in life. I learned to think things through before acting. I learned that your first instinct isn’t always the best, even if in the end you circle back to it. I learned that you took the time needed to get something right and that you ignored the many distractions; you focused and you went deep into yourself.

In front of a little green monster of a machine, you confronted the limits of your imagination through hundreds — thousands — of possibilities and you made choices. And then you undid them and started all over again in search of something inexpressible.

In that space, in those moments, something extraordinary was being created. It was both simple and endlessly mysterious.

John Coles

(Editor’s note: The above remembrances of Barry Malkin were excerpted and edited from speeches given at his memorial service in New York City on May 1.)