Go to part 2.

Frank Urioste and Peter Honess met in 1966 when both were assistants on The Dirty Dozen. In the years since, Urioste has edited such films as Basic Instinct, Total Recall, Die Hard (with John Link), RoboCop, Cliffhanger and Midway (with Robert Swink). He has now moved into the executive suite as a senior vice president of feature development at Warner Bros. Honess’ many films include L.A. Confidential, Mercury Rising, Six Degrees of Separation, this summer’s The Fast and the Furious and his current project, Domestic Disturbance. Though this story was intended as an interview, it quickly turned into something more: an intimate chat between two longtime friends and colleagues about their films, their careers and the changes they’ve seen in the business.

Urioste: We met on The Dirty Dozen, and it was really a very difficult film. That movie was almost five hours in first cut.

Honess: I remember, because I used to take it down to the theater in endless loads on the trolley. It was run constantly in preview theaters with the editor and the director. But to my knowledge, the director, Robert Aldrich, never came into the cutting room. I think he once stood in the doorway.

Urioste: That’s the way we were taught at MGM. I never had a director in the cutting room with me. They made their comments, they came in and looked at something, but when I cut, I cut by myself. Today, a lot of the directors want to sit there. I don’t think it’s a good thing, because you’re not getting the editor’s point of view.

Honess: In the past, the director would give notes and go away. Now, they sit right beside you, because what used to take the afternoon takes minutes. Directors feel that they’re accomplishing something by sitting beside you, but that’s not always true. You lose the thinking time and the rationale of it all. A lot of editors complain about this now.

Urioste: I was lucky – my mentor, the man who really taught me was Ralph Winters. I think he was the greatest editor who ever lived. He did all the big stuff at Metro – from Singing in the Rain to High Society to Ben-Hur. He’s amazing, and he really, really helped me. I’d say Ralph Winters made me what I am today.

“When you have two editors, there can be no egos, which is really great.” – Frank Urioste

Honess: I had an English mentor – Tony Gibbs. I didn’t pay attention for quite a few years to what the editor was actually doing – a lot of assistants just assist, they don’t actually know how the editor does it. Later on, I made myself try and watch what Tony did. When he went home at night, I used to wind through his cuts on a synchronizer and see how he put things together. I don’t know if it happened to you, but the first time I edited – not just putting bits and pieces of the film together for the editor, but actually cutting my own movie – I found it quite terrifying, because suddenly you’re left to do the storytelling yourself.

Urioste: Absolutely. I can remember being given my first sequences. “Go ahead and put this together for me tonight,” Ralph would say. I’d act like, “Oh, that’s a piece of cake,” and all of a sudden, I’d try to make my first cut and I’d be going nuts. I didn’t realize how tough it was. The first time I did it, it took me forever just to get the first cut done. I’m not talking about the first scene, I’m talking about going from the master to the first close-up. Whenever I’d do a sequence for Ralph, I was always doing stuff the way I thought he would do it, and that’s a terrible mistake. If you’re the editor, you’ve got to put it together the way you envision it. I think that was the biggest thing Ralph taught me.

Honess: The first film I cut, I was thinking, “How would Tony have done this?” I was obsessed by it. Eventually, you realize that this is ridiculous. I let assistants on my films cut anything they want to, and I say to them, “You must forget all about me. Don’t worry about what I’m going to say, or what I’m going to think. Cut it for yourself. You be the audience.”

Urioste: Absolutely.

Honess: The audience is a very important factor in my work. I think about them constantly – will they understand, can we frighten them, can we excite them? It’s actually not a bad idea for assistants to have that in mind when they first start working, and not try and impress their editor.

Urioste: You and I worked with very tough people when we were kids – and I always made it a rule that unless somebody’s really out of line, I never get angry at all, I try to keep it light. Editing is a very tedious, tough job and when it gets tense, and people lose their sense of humor, they don’t do their best work. I think some editors today are a little too tough on their guys, and I think it comes out of insecurity.

Honess: It’s a strange form of behavior – to take it out on your assistants, because you can, because they have to take it. It’s very abusive.

Urioste: I used to take it a lot. The editors were tyrants in those days.

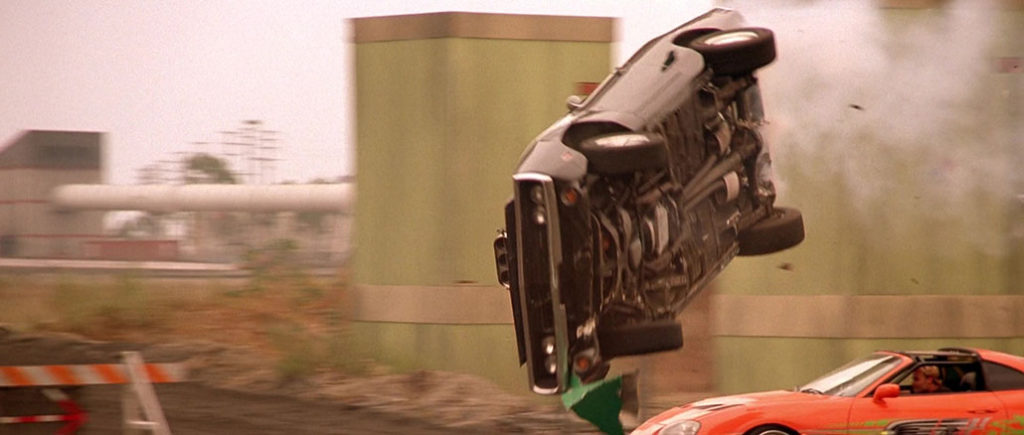

Honess: There’s something I wanted to talk to you about – the tendency now to pigeonhole us, either as comedy editors, action editors or drama editors. It really bothers me.

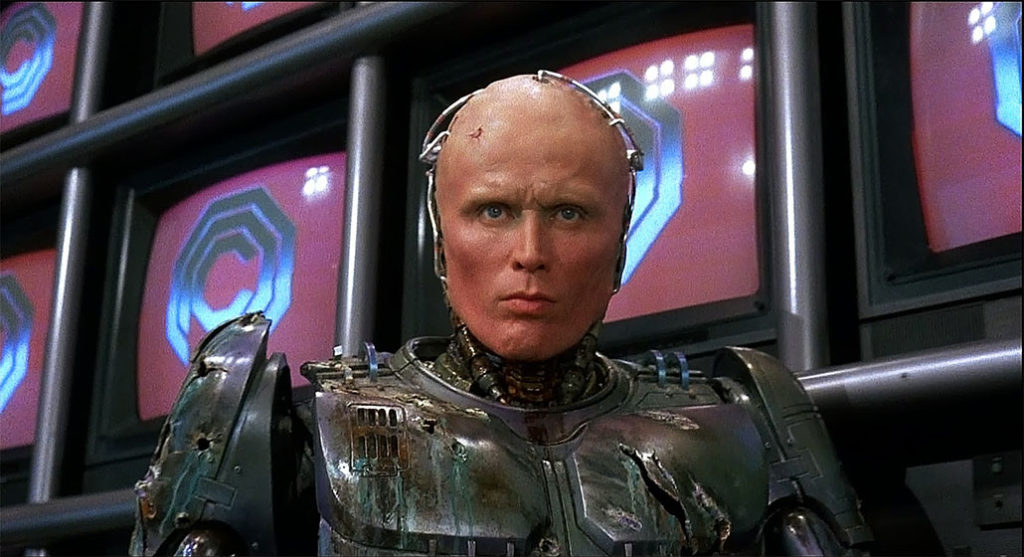

Urioste: Bothers me too. I’ve said that in meetings at Warner Brothers. I think that a good editor can edit anything. People talk to me about the action stuff I’ve done, but I say, look at all of them – RoboCop or Die Hard or Lethal Weapon – they all had a lot of laughs in them, heavy duty comedy. Basic Instinct only had 18 seconds of action in the whole movie. The rest is all talk, and they still consider it action. I was just given an encyclopedia of people in Hollywood, and it had me categorized as “a fine action editor who had numerous box office hits during the ‘80s and ‘90s.” That was it. I’m glad they liked it, but there’s a lot more in the movie than action – or else you have no movie.

Honess: I think it’s a convenience for some producers to think of us that way. They’ll ring up an agent and say they need a comedy editor. What is a comedy editor? I actually cut The Fast and the Furious, which was a non-stop action film, just to say, “Listen, I’m a film editor, I can cut dramatic pieces and I can cut action pieces.” I want to do a comedy now, so I can show I can do that as well. I cut Disney’s The Kid with a young editor, David Rennie, very talented, and we talked about this all the time. It was my first experience of cutting with another editor. You’ve done a few films, haven’t you, with someone else?

Urioste: Oh sure.

“Some of the cutting – I have no idea how it happened. You don’t remember it particularly as an individual moment of editing. It’s just something you felt at the time.” – Peter Honess

Honess: But this one we did together right from the get go. I was told up front, if you want to do this, there will be another editor. I’d never done it before, but I really enjoyed that process.

Urioste: I only did one film like that, Midway. But I was on the film about six months before it started shooting, to cut together all the battle scenes using actual footage from World War II. Then when the movie actually started shooting, Bob Swink came on. He was going to do the Japanese scenes, and I was going to do the American scenes. Bob left before we finished the movie, because he had something else to do, but that’s the only time I ever had anybody on right from the beginning. Actually I would have been considered the second then – Swink was a big-time guy in those days.

Honess: Did you enjoy it?

Urioste: I did kind of, but you know me, Pete. I have my way of doing things. When you have two editors, there can be no egos, which is really great. You have to just do it and be able to take some criticism. Or there’s got to be one guy that’s the boss. That’s the way it was with me, anyway. The last few films, I had guys who were my assistants at one time, like Kevin Stitt and Dallas Puett and Derek Brechin. I let all those guys cut with me and gave them credit. They got experience, and now they’re all cutting.

Honess: That’s a terrific way of bringing assistants on. I do quite a lot of talking at seminars and universities, and everybody asks how the assistants learn to edit. It’s gotten harder now, because when I cut on an Avid, what can an assistant be doing in the room? They don’t have time to sit and watch, and sadly, you don’t need them there to help, like you used to.

Urioste: When I was working with Ralph Winters, and we would run the film with the director, I would write all the notes out. After we finished, before Ralph would come in, I would read all the notes over to myself and I would get out all the film. I had to think of what he needed to make these changes. Today, on the Avid, you pull up a scene, everything is just there and you do it yourself. The kids don’t get the opportunity to figure out how you’re going to do it, because it’s all sitting right there on the Avid.

Honess: When the editors I worked for first put a scene together, you could tell how they cut it by what they hung in the trim bin. If it was just a front trim and an end trim, they had used only one piece of that shot. If there were three pieces of film, then they used the shot twice. You knew, because you had to put the bloody stuff away. And you learned by osmosis. Every time you put a piece of film away, you realized what he was using, and every time you pulled a trim out, you were part of the process that was going through the editor’s head. Unfortunately, we’re not able to do that now. It’s a major responsibility for all of us editors – how do we pass the craft on? It’s all done so quickly now and you’re not going to be sitting at an Avid explaining every cut. That’s why I tell these kids they can take any scene and cut it for themselves, and I’ll look at it, and I’ll incorporate it into the picture once we’ve worked on it together. It’s not difficult to use an Avid – just because you can use an Avid doesn’t make you an editor. Unfortunately, there are some directors who think they should cut the film themselves. Some do, in fact, because it’s much easier to use an Avid or a Lightworks than it is to use a Moviola.

Urioste: Absolutely.

Honess: Film terrified everybody except the cutting room people. They’d come in and gingerly touch the film. It was a very intimidating place for everybody but the editing crew, and I loved all that, because it added an aura of mystery.

Urioste: It’s amazing. I’d ask someone to hold a piece of film if I was doing something really fast. They would act like they were grabbing onto something that was going to bite them.

Honess: But with these electronic machines it’s so simple. It’s fun to have been around in a time when the whole mechanical process of cutting film changed. That’s a seriously different situation in one’s professional life, and it’s probably happened to very few other people. I think we’re very lucky to have been part of that process.

Urioste: On my first film, we weren’t even using splicing tape yet. I had to run downstairs and use the hot splicer for both picture and track. You lost a frame with every cut, so if you had to put two pieces of film back together, you had to splice in leader, or what we called black frames. Then splicing tape came, and we didn’t have any black frames any more. Then the electronic systems came, and now we don’t have splices at all.

“Editing is a very tedious, tough job and when it gets tense, and people lose their sense of humor, they don’t do their best work.” – Frank Urioste

Honess: When did you make the transition to digital?

Urioste: I only did one film digitally, believe it or not. On Conspiracy Theory I cut one scene that way, a montage. But the only film I ever cut digitally, in its entirety, was my last picture before I took this job, Lethal Weapon IV. I couldn’t have done it without electronics. 33 days from the end of shooting, we were in release.

Honess: This is actually my eleventh film on digital equipment. I started using it eight years ago. I had to be kicked screaming into the electronic world by the director, Fred Schepisi. Fred insisted that we try this process, which was very juvenile in its development in those days, and God bless him for it.

Urioste: But no matter what the equipment is, it all comes back to the individual. Paul Verhoeven and I did a little seminar with some professors from around the United States, and they would ask, “Are there any rules you guys have?” I’ve never had any rules. Robert Aldrich was the one that used to have rules, where you never cut straight in, for example. I remember arguing with him one day on a picture called The Grissom Gang. He told me that when my name was on the door, I could cut it any way I want. Certain things are wrong in editing – crossing the line is an example – but as far as where you cut, it’s all a matter of taste. That’s what makes some people good and some people not so good.

Honess: It has to be a natural thing – instinctive. I sometimes go back and look at the films that I’ve done before. I don’t make a habit of it, but if one is on TV, I might watch it for a while. Some of the cutting – I have no idea how it happened. You don’t remember it particularly as an individual moment of editing. It’s just something you felt at the time.

Urioste: When I started working with Paul Verhoeven and we did RoboCop, he told me that he really wanted me because I was unconventional. He did not know when a cut was coming. I always feel that I’m extremely conventional – that it’s so obvious where the cut should go.

Honess: I used to plan scenes very carefully when I cut on film. If you cut it too deeply, you had to go and get the trim out and put it back on again. You didn’t want to hang around waiting for the assistant to find those six frames that had been put away the day before. It’s a different process now – some editors just rough the whole thing out and then go back and smooth it. They cut in chunks, and they don’t plan so much, because they don’t need to. I still use the same technique, which is to look at all the film first, and then write in the script where I want to cut. But whatever you do, do not cut the director’s moves out – especially on the first pass!