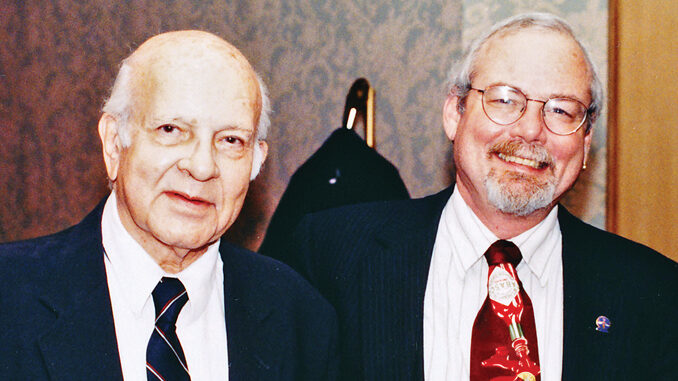

by Betsy A. McLane • portrait by Gary Galvin

Hollywood mythology has it that a determined person can start in the mailroom and end up at the top of the business. While very few people actually make that myth become a reality, Randy J. Roberts, A.C.E., is living proof that it can happen.

Roberts’ dream since childhood was to be a top editor. So it is apropos that he was chosen to receive the American Cinema Editors’ (ACE) Heritage Award this year. The honor is a fitting tribute to a man who embodies the tradition and transitions in Hollywood editing over the past 50 years.

ACE does not give the Heritage Award every year; the last recipient was longtime Guild member Ted Rich, A.C.E., in 2006. The award is given in special recognition of an individual’s unwavering commitment to advancing the image of the film editor, cultivating respect for the art and craft of the editing profession, and tireless dedication to American Cinema Editors. The Heritage Award was presented to Roberts by ACE President Alan Heim, A.C.E., February 7 at the 64th ACE Eddie Awards at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills.

CineMontage interviewed Roberts in January.

Roberts served on the ACE Board of Directors since 1996, was Vice President from 2005 to 2008 and President from 2008 to 2012. He is currently the Director of Marketing. His professional philosophy — “Editing is a mental process. The machine simply lets us see that process” — is particularly apt for a man who witnessed, and practiced, the evolution of technology from the upright Moviola to the Avid.

Roberts was born into a film family and raised in the shadow of Warner Bros. studio in Burbank. His father, Jack G. Roberts, was a casting director at Warner, and by the time Roberts was 10, he had been an extra in The Bad Seed (1956) and appeared in a television commercial that introduced Kellogg’s Special K to the world. His uncle, Sam O’Steen, A.C.E. (1923-2000), was the renowned editor and a mainstay on the Warner lot. O’Steen edited most of the pictures directed by Mike Nichols, beginning with The Graduate and including Catch-22 and Working Girl, and was also known for his work on Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby and Chinatown.

After 11 years at Warner Bros., Roberts became a freelance editor or, in his words, “a gun for hire.” This period led to work with Francis Ford Coppola on One from the Heart and Hammett, both released in 1982.

With this pedigree, it might seem that the way would have been easy for Roberts, but he started at the bottom in 1965 at age 19, literally sorting mail for three years at Warner Bros. He began to give visitors studio tours, which were then modest, informal affairs, since no one else wanted the job. Roberts was thus often on the sets, but the editing rooms were his favorite hangout.

These were the years when the studio system retained some hold on the industry, in both film and television. Jack L. Warner was still running the business, and the legendary Rudi Fehr, A.C.E., who worked there from 1940 to 1976, ruled the editing department. Since many people had worked there for decades, an almost family-like environment prevailed on the lot. Roberts haunted the editing rooms long after his day job was over. He was welcomed there, not only for his fascination with looking over the shoulders as work went on with upright Moviolas, but also for his ability to keep score at the apprentice’s ongoing gin rummy games.

Despite his father’s hopes that he would become a lawyer, Roberts wanted to work in the industry; he left Valley College and was taken on as an apprentice at Warner. He immediately joined the Editors Guild and began to work his way through the seniority system then in place. Roberts served as an assistant on The Steagle (1971), Freebie and the Bean (1974) and Sparkle (1976, directed by O’Steen). His first editing credit was the Richard Pryor action comedy Greased Lightning (1977).

After 11 years at Warner Bros., Roberts became a freelance editor or, in his words, “a gun for hire.” This period led to work with Francis Ford Coppola on One from the Heart and Hammett, both released in 1982. Roberts notes that director Coppola had recently returned from arduous months in the jungle making Apocalypse Now and had developed an aversion to being on set. One from the Heart, with a musical score as its basis, was shot entirely on five sets and one backlot.

The film was Coppola’s first attempt to consolidate all aspects of production into one central electronic hub. He wanted to find ways to apply electronic technology that would increase production efficiency without compromising the quality. One outcome of this experiment was the Silverfish — an Airstream RV that provided audio support sets as well as an environment for both creating and editing film. It was equipped with video-viewing machinery, a hot tub and a pink interior. With wires attached to each of five stages, it captured the sound and images from all of them.

The Silverfish challenged workflow standards by enabling pre- production, production and post to occur simultaneously. With the potential advantages of using videotape alongside film, the taped images were viewed and edited (with linear equipment) as they were shot, providing a guide for the next day’s shoot. Roberts sat in the trailer working with Coppola in a new way that at first he found challenging.

Although One from the Heart received a mostly negative response and earned a reputation as one of the biggest money- losers of all time, Coppola developed a way for editors to be an intimate part of the filming process. The picture remains an overlooked tour de force of visual style, and though most editing is still done off the set, there is much more pressure to produce fast dailies than there was in an era when film ruled. Another technical innovation for Roberts came with Jaws 3-D (1983). For this project, he developed a way to simulate the 3-D experience while editing. He actually devised a prism mechanism for a KEM that allowed one image to be split into three — a technique that Roberts believes has not been used since.

Television was the next leap. With the 1985 TV Movie Kids Don’t Tell, directed by O’Steen, Roberts shifted to the smaller screen. Around the same time, he was asked by producer/director/writer Chris Crowe to re-cut a pilot for Universal. It was for a new TV movie based upon the 1950s series of the same name, Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1985-89), which combined newly filmed stories with colorized footage of Hitchcock from the original series to introduce each segment. The movie was a huge ratings success, and even sparked a brief revival of the anthology series’ shows. Roberts edited five episodes and quickly became one of Hollywood’s top television editors, working on shows like Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94), L.A. Law (1986-94), Chicago Hope (1994-2000), Early Edition (1996-2000) and others. He was nominated for an Emmy Award in 1995 for Outstanding Achievement in Editing for a Series-Single Camera Production for the Chicago Hope episode “The Quarantine.” He was also nominated for an ACE Eddie Award for Best-Edited One-Hour Series for this episode.

Upon joining ACE in 1993, Roberts became one of the organization’s most vocal advocates and strongest leaders. He not only volunteered many years of service on the Board of Directors, but had taken the advancement of the editing profession as a personal mission.

Other Eddie nominations were for the 1993 L.A. Law episode “Say Goodnight, Gracie” and a 1998 episode of Early Edition, “The Wall Part 1.” Roberts won an ACE Eddie Award in 1997 for the Chicago Hope episode “Transplanted Affection.” He also directed episodic television dramas, but found that he much preferred editing. The three years he spent directing as a self- titled “gun for hire” produced some of “the worst and best days” of his career. What Roberts loves about television editing is the fast pace. He also finds as an admitted procrastinator that he works best under the pressure of a weekly series.

In addition to his accomplishments as editor and director, Roberts was co- producer and supervising producer on the television series Early Edition and co-producer and producer on the drama series Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (1999-present), ultimately working on 217 episodes between 2001 and 2011. His screen credit was supervising producer, and in this position he was responsible for overseeing all the post-production for the series. On Law & Order, he put to good use his well- honed skills at “editing room politics.” For Roberts, this included a responsibility to “protect” the work of the show’s editors and assistants from unreasonable demands and intrusions. Roberts credits his longtime editing colleague Arthur Forney, A.C.E., for much of the success of Law & Order.

Upon joining ACE in 1993, Roberts became one of the organization’s most vocal advocates and strongest leaders. He not only volunteered many years of service on the Board of Directors, but had taken the advancement of the editing profession as a personal mission. He was instrumental in establishing EditFest in the US in 2009, after representing ACE at the existing Edit Festival in Frankfurt, Germany.

Roberts was able to take the idea across the Pacific and create what has become an institution in the field. He helped ACE garner recognition at NAB and festivals around the world by creating film editing panels and editing awards. Further, Roberts helped to implement Tech Day for the organization’s membership to remain top of their field in technology. He remains dedicated to enhancing the understanding of what editors contribute to television and film, both to the public and to students, by actively promoting and participating in the ACE student film competition and its highly sought-after editing internships.

Roberts’ own editing heroes include his uncle O’Steen, Fritz Steinkamp (They Shoot Horses Don’t They?, 1969; White Nights, 1985) and Gene Milford — who received ACE’s inaugural Career Achievement Award in 1988 — especially Milford’s work on Lost Horizon (1937).

His advice for those who want to enter the business is to sit with an editor and watch the process. There, someone can learn the tricks of the art, perhaps even how to make what Roberts believes is the hardest edit — a person walking through a door. Ultimately, he wants editors to remember, “It’s about storytelling, not about the edits. It’s about how to tell the story best.”