by Kevin Lewis

A Letter to Three Wives was a classic from the day it was released in January 1949. It won two Oscars for Joseph L. Mankiewicz — Best Writing (Screenplay) and Best Director — a feat he repeated the following year with the same awards for All About Eve (1950). Seen today, there is still much truth in Three Wives’ analysis of marital relationships in suburbia. The television series Desperate Housewives could be an update of sorts, but Mad Men, set only a decade after the Mankie- wicz movie, further augments the psychological themes of the film.

Mankiewicz was not the initiator of the script, which was based on a 1946 Cosmopolitan magazine novel called A Letter to Five Wives by John Kempner. Writers Melville Baker and Dorothy Bennett worked out the problems in this multi-character story, which Baker partially solved by making the town temptress, Addie Ross, an unseen character and narrator. Vera Caspary, the author of the hit Fox film noir Laura (1944), adapted the story, eliminated one wife (making it A Letter to Four Wives), and worked with Mankiewicz, who was assigned as director.

Mankiewicz regarded himself as an auteur, long before the term was applied, but Zanuck relied on film editors, rather than writers and directors, to hone Fox’s films.

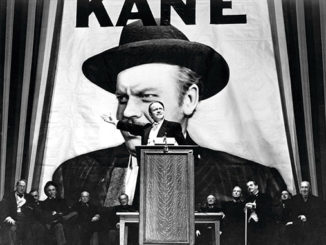

A screenwriter earlier at Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Mankiewicz, now at 20th Century-Fox, considered himself a writer/director along the lines of Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder. His older brother, Herman Mankiewicz, co-wrote Citizen Kane (1941) with Orson Welles and won an Academy Award. The younger Mankiewicz’s script for Three Wives was 190 pages long, so producer Darryl F. Zanuck cut the plotline in which Anne Baxter was originally cast, reducing the story to three wives.

Because the film was produced just after World War II, it still reflected the strides women made during the war. Returning veterans — some of whom were previously the Depression-era rural and urban poor — made the leap into corporate America within a few years, bypassing social barriers. Many women advanced economically also because they either served in the Armed Forces or took jobs because the men were at war.

The three wives fit that bill. Deborah Bishop (Jeanne Crain) left the farm and her past behind when she became one of the WAVES. She married a naval officer, who was upper class. During the war, they were on an equal social footing, but afterward, she realized her second-class status.

Lora Mae Hollingsway, nee Finney (Linda Darnell), became an employee — and more — of department store owner Porter Hollingsway (Paul Douglas), and soon left her shack by the tracks for his mansion when she demanded marriage or nothing. But she was considered to be an opportunist by the city as well as her husband.

Rita Phipps (Ann Sothern) became a well-paid radio soap opera writer because the men were at war, but this proved to be a pyrrhic victory because her intellectual but underachieving schoolteacher husband George (Kirk Douglas) resented his wife paying the bills so they could live in a home “where those on the way up live alongside those on the way down.”

The letter to the three wives is written by local social goddess Addie Ross (Celeste Holm), who is never seen but narrates the film. It is hand-delivered to them while they are on a boat trip for children. Addie states that she has left town with one of their husbands. In those pre-cell phone days, the wives will not know until the evening which husband is missing. So they review their marriages, and recall social inequality (Deborah), breadwinner problems (Rita) and suspicion (Lora Mae). The three suburban wives fear Addie, the object of their husbands’ admiration, to the extent that they believe her letter to them. But logic suggests that the husbands knew Addie for years before they married their wives and would have married her if they desired. Addie is a metaphorical character for the viewer, the crystallization of the wives’ sexual and social insecurity.

Mankiewicz could delineate social classes in a few witty lines and situations. Deborah is angry when her husband Brad (Jeffrey Lynn) suggests that she buy the same evening gown that Addie had worn to a country club dance, and recalls the outmoded, frilly ball gown that she herself wore when Brad introduced her to his friends.

Lora Mae’s home life before marriage reveals why she had to escape. While she is waiting for a date with Porter, her mother (Connie Gilchrist) and friend (Thelma Ritter) are sitting drinking beer at the kitchen table in the shack just feet from the tracks. Every time the train roars past, both women shake up and down and hold their beer glass aloft to keep from spilling.

As raspy-voiced maid and cleaning lady Sadie Dugan, Ritter steals the movie, and also delivers the line that expresses Mankiewicz’s contempt for lowbrow radio writing. Later, in the Phipps’ kitchen, while preparing the canapés for the dinner Rita is giving for her radio producer boss (Florence Bates), Sadie says that she likes Rita’s soap opera “because even when I have the vacuum cleaner running, I can understand it.” The dinner is a disaster when highbrow George insults both the program and the boss, causing the rift in the marriage.

Mankiewicz regarded himself as an auteur, long before the term was applied, but Zanuck relied on film editors, rather than writers and directors, to hone Fox’s films, and assigned to Mankiewicz his trusted editors Barbara McLean (All About Eve), Dorothy Spencer (The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, 1947) and J. Watson Webb, Jr. (A Letter to Three Wives). Left to his own devices, Mankiewicz was a verbose writer with complicated flashback and narration structures, and his career floundered after he left Fox to become an independent producer/writer/ director. Not surprisingly, when he returned to Fox to make Cleopatra a decade later, it was his overlong script which caused the crisis that nearly sunk the studio.

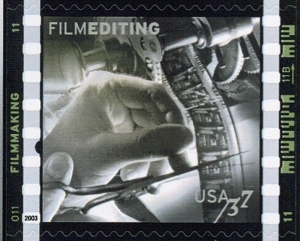

Webb, a gifted editor of many Fox classics, including State Fair (1945), The Razor’s Edge (1946) and Kiss of Death (1947), was never nominated for an Oscar, but he is immortalized on the American Filmmakers post-age stamp honoring editing that was issued by the US Postal Service in 2003 (they are his hands shown editing The Razor’s Edge). Webb was one of the finest performance-oriented editors in the industry, adept at an ensemble film. He was an American aristocrat, the great-great grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt on his paternal side and the grandson of the sugar tycoon and art collector Henry Havemeyer on his maternal side. He was also the longtime lover of the great sex symbol Tyrone Power, who was the main male star of 20th Century-Fox and married to the actress Annabella. Though he was one of the main film editors at Fox, Webb left the studio and his profession in 1952 when he was only 36 years old to manage the Shelburne Museum in Vermont, which was founded by his art collector mother, Electra Havemeyer Webb.

A Letter to Three Wives hasn’t really dated because Mankie- wicz wrote scripts that were sophisticated without being brittle, about people who wore masks but were sympathetic. Caspary and her producer husband I.G. Goldsmith tried to make lightning strike twice when she wrote the movie Three Husbands (1951), about a dead playboy who leaves a letter to three husbands stating that he had an affair with one of their wives. It was a mild success but was soon forgotten.