by Robin Rowe

Frank Miller’s Sin City represents a new breed of digital filmmaking. It’s a practical example of what the 4:4:4 HD filmmaking revolution is about and its creation is a demonstration of the workflow that filmmakers use to create digital films of striking image quality.

Sin City, already released, beat the impending Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith into theatres, becoming the first film out of the gate to use a workflow of Sony HDC-F950 cameras with the Sony 4:4:4 RGB HD-CAM SR tapes and digital intermediate (DI).

The New Digital Pipeline

For many years the state-of-the-art in filmmaking has been to shoot 35mm film, scan the film into digital intermediate format (typically DPX), composite special effects using Apple Shake, create an offline low-resolution copy to edit with Avid Composer or Apple Final Cut Pro, print the DI effects sequences back to film, then conform to match the offline edit by physically splicing film. To cut costs, the B-movie industry has used television gear end-to-end instead, but the image resolution and color was noticeably less compared to productions originated on film and pipelined in digital intermediate. Upgrading to HDTV cameras brought substantial improvement, but achieving the image quality of film has been elusive.

A new breed of 4:4:4 HD cameras such as the Sony F950 and Thompson Viper offer better picture fidelity than previous 4:2:2 HD cameras. HD can be handled like scanned 35mm film when converted into DPX digital intermediate format.

Rodriguez’s Vision

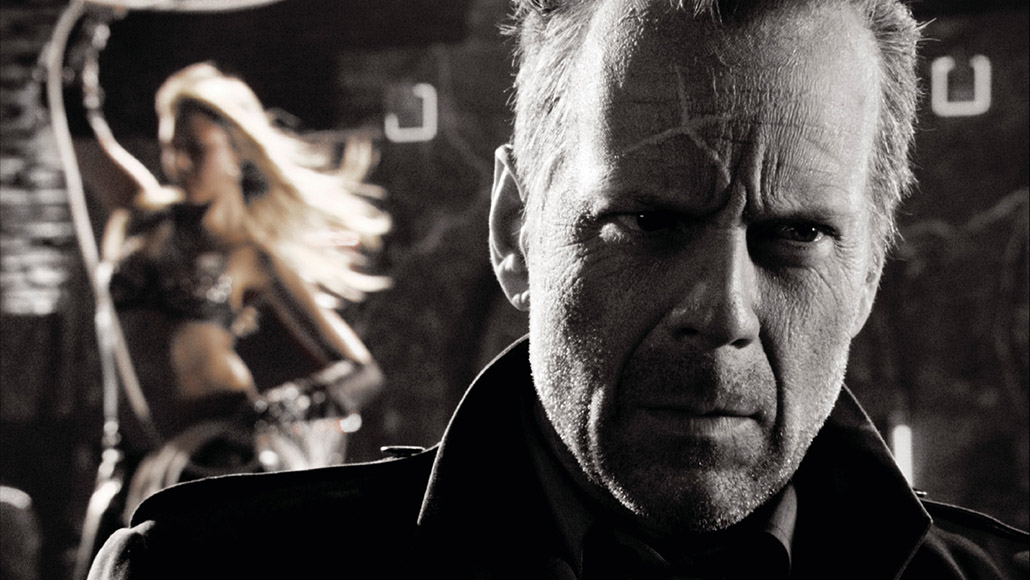

Director and editor Robert Rodriguez resigned from the Directors Guild of America so he could co-direct Sin City with author Frank Miller. The film, a no-holds-barred city noir based on three of Miller’s graphic novels, was shot with Sony F950 cameras on HD-CAM SR format. Sin City was edited by Rodriguez at his Troublemaker Studios in Austin, Texas. Stylistically, it is mostly in black-and-white, with occasional color in elements such as lips or eyes.

“When I read [Miller’s] books, I felt that they were fantastic exactly as they were”, says Rodriguez. “I loved that the dialogue didn’t sound like movie dialogue, that the visuals didn’t look like anything you usually see in movies. It was so much more unpredictable than any screenplay. So I wanted to bring Frank’s vision to the screen as it was. I didn’t want to make Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City. I wanted to make Frank Miller’s Sin City. I knew that with the technology I already knew how to use–lighting, photography, visual effects–we could make it look and feel exactly like the books.”

Rodriguez approached Miller saying, “Why don’t we shoot the opening scene on a Saturday with my crew and some actor friends, [Josh Hartnett and Marley Shelton]? My effects company [Troublemaker] will add the effects, and I’ll score it and complete it up through the opening titles.” That footage, shot in just ten hours time, convinced actor Bruce Willis to play Hartigan. “It was just riveting,” recalls Willis. “I’d been a fan of Frank Miller’s Sin City for a long time–I’ve always been a fan of dark, poetic, hard-bitten stories–but I didn’t think anyone could come up with a way to actually shoot them until Robert invented this new digital filmmaking style.”

“The trick was to capture what’s visually startling about the books,” adds Rodriguez. “It had to be shot entirely on green screen because the visuals and lighting in Frank’s books are physically impossible.”

How It Was Done

Troublemaker used 4:2:2 HD-CAM on past shows such as Spy Kids 3-D. HD-CAM SR, a new Sony 4:4:4 RGB format, was used to shoot Sin City and to exchange footage with the effects houses–where it was converted to digital intermediate DPX. However, Troublemaker didn’t use a DPX pipeline. Onlining of the film started on a Quantel eQ at 501 Post in Austin where Rodriguez could approve the online and video space color correction–to get the look in the ballpark. Reels were transferred from 501 to Post Logic as archived data, something 501 and Post Logic helped pioneer for this show. At Post Logic, it was seamlessly picked up in the Quantel iQ. Shots finaled at Post Logic were assembled into finished reels then shipped on HD-CAM SR tape to EFILM for the final color correction and film-out.

“Since I shot in color, we’d take the color out and make it a stark black-and-white, but at any time in post I could bring a color back in,” says Rodriguez. “You could then use color as a weapon; a really strong storytelling tool. So you have a character like Goldie, who pops out with real flesh tones and blonde hair, or The Yellow Bastard with his mustard-colored skin. And when I wanted to heighten a character’s pain I turned the blood red, which really brings it into the foreground, almost like a color close-up.

“At the same time, we could temper some of the more gruesome images, by making the blood that very cartoonish white you see in the books, which keeps it from being overwhelming,” he continues. “It becomes very abstract.” Rodriguez had the Yellow Bastard painted blue, so that in post they could get a better key off of him and do a hue shift that would turn him yellow.

Visual effects were created by The Orphanage in San Francisco, CafeFx in Santa Maria, California, and Hybride near Montreal. Each effects house independently developed its own creative look, honoring the style of Miller’s black-and-white illustrations and Rodriguez’s vision for the film. The rough edit was done at 501 Studios in Austin, final edit at Post Logic in Hollywood and film-out was at EFILM in Hollywood.

The Orphanage received 4:4:4 RGB-formatted HD-CAM SR clones of the camera masters shot with the Sony HDC-F950 camera. “We received plates shot on green screen from Troublemaker Studios, and created 3-D environments and digital matte paintings,” says head of editorial Carl Walters. “We also ran effects animation and composited each shot.” Working on Windows 2000 workstations, the editorial team created digital matte paintings in Photoshop CS, 3-D environment models in Discreet 3ds max, falling snow in Houdini, and car animation in Maya. SplutterFish Brazil was used for rendering the environments. Windows After Effects was used for compositing, plate manipulation, and time remapping.

The Orphanage workflow had a RaveHD DDR ingest the 4:4:4 HD-CAM SR tapes and write them out as DPX file sequences onto a 2TB dual fibre disk array. An internal plate processing macro driven by Digital Fusion created 4:2:2 HD BlackMagic-encoded Quick-Time proxies for quality control and dailies. “Robert would send us EDLs of his changes to the cut,” says Walters. “He would approve shots as final by looking at Quicktime files that we would post to his FTP server.” The Orphanage did a shot-by-shot color correction prior to Rodriguez calling a shot final. RaveHD was then used to print the final DPX frame sequences back to 4:4:4 RGB HD-CAM SR tapes to go back to Texas.

Hybride special effects director Daniel Leduc oversaw 735 shots to deliver book one of Sin City. The F950 was set to record 4:4:4 RGB at 10-bit (higher quality than the 4:2:2 YUV 8-bit typical for HDTV). “The project was shot mostly in the studio on green screen, like Spy Kids 3-D”, says Leduc. “Then it was imported into Inferno at 12-bit through the Discreet Smoke on SGI Tezro built-in dual-link SDI board.” SoftImage|XSI was used for most D, except for particle effects–such as the rain effect–created in Maya. SoftImage and Hybride are both based in Montreal.

Leduc found it unnecessary to render all the 3-D layers in 16 bits, which would take too much time and space. “Some layers were done in 8 bits and mixed with others rendered at 16 bits, such as fog, lighting and depth of field,” says Leduc. “Without any noticeable difference, we composited those layers together and created a final image at 12 bits.”

The Inferno shots were finaled in 12-bit, then exported back to HD-CAM SR in 10-bit through Smoke on Tezro. “Using 12-bit left room for final color correction,” notes Leduc. “501 did research on color correction with Robert.” Input and output was on Smoke for offline conform of all different elements, and Final Cut Pro was run on the side to check progress and continuity. During shooting, two monitors were used. One with the full tonal range, the other adjusted for high contrast to preview the look of the final film for Rodriguez. “Three different studios created the style of each book of the film independently,” says Leduc. “Normally, when many houses work on a movie together they try to blend, but for Sin City the goal was to keep the look of each book different.”

CafeFx produced the visual effects and virtual sets for “The Big Fat Kill,” one of the three books in Sin City. “All of the actors were shot on green screen using the new Sony SR HD Camera and VTRs,” says digital effects supervisor David Ebner. “We captured the footage into our Final Cut Pro HD edit system, preserving the dynamic range of the 4:4:4 signal.” The 3D and compositing work was done in floating point to preserve the full bandwidth of the image for maximum flexibility. “We colored our 600+ shots with a Sin City high contrast black-and-white look and also did over 200 extra deliveries with color additions for Rodriguez,” says Ebner. CafeFx effects included water, rain, explosions, car crashes and digital stunts.

Guest director Quentin Tarantino worked for one day on the scene from “The Big Fat Kill,” in which the characters Dwight and Jackie Boy drive through the rain with Dwight convinced that the dead Jackie Boy is talking to him. “Robert couldn’t have picked a scene that better illustrated the uses of digital filmmaking,” comments Tarantino. “You have this rain pouring down on the car, you have a ton of water hitting the car, and you want to have every water drop illuminated–just the way it’s drawn. I realized if I was shooting this on film, it would take forever to get that going, and the sounds would have been ruined. But instead of being stuck with capturing everything perfectly, it became entirely about the delivery and the performance.”

Understanding the Technology

It seems daunting, all this new technology. Here’s a breakdown.

The human eye, film and digital sensors each respond to light in different ways. The eye and film see colors on a logarithmic scale, but digital sensors output linear color ranges like computers use. NTSC television cameras use a luminance channel and two half-resolution color channels–4:2:2 Y’CbCr. Computers prefer three full color channels–4:4:4 RGB.

What’s ironic is the tremendous improvement DI is bringing to film prints, making a proven technology look much better.

DPX is a logarithmic image format used for digital intermediate. As a file format, it’s something like TIFF, but because DPX is in log space it can efficiently hold data from film scans. HD can be converted into DPX with a device such as RaveHD. The RaveHD DDR has a dual-link SDI input. SDI is a wire, sort of like Firewire. A single channel of SDI carries 4:2:2 and the second channel of SDI is needed to carry the additional 0:2:2 to make 4:4:4. One can plug a Sony HD-CAM SR deck into a RaveHD, and convert HD-CAM SR tape output into sequentially numbered DPX frames to be served by RaveHD over NFS (Linux) or Samba (Windows). RaveHD is fundamentally a Linux PC with an AJA io board and RAID storage. RaveHD isn’t the only option for converting between HD-CAM SR and DPX. Sin City also used Autodesk (formerly Discreet) Smoke and Quantel.

But what about bits? DPX files are typically 10-bit. Computers don’t handle log data easily, so as DPX files are read into memory software converts them to linear. To accommodate this mathematical expansion into linear space, another 2 bits of capacity are needed. But, 12-bit linear is unwieldy. Computers like data to be 8-bit, 16-bit, or 32-bit chunks. So, DPX usually gets converted up to 16-bit linear for visual effects. As with audio, more bits per channel is better with HD images. The HD-CAM SR format records 10-bit streams from the F950 (although the camera has a 12-bit DA). To hold 10-bit 4:4:4 RGB required a breakthrough in recording tape technology. HD-CAM SR has double the data density of HD-CAM.

One more thing about bits: DPX may not use the entire range. Mathematically, a 10-bit number can range from 0 to 1023. But, dynamic range encoded into DPX is often from 60 to 900. Because SMPTE reserves some numbers, the dynamic range of HD CAM SR is from 4 to 1019.

And then there’s resolution. According to Troublemaker production supervisor Keefe Boerner, “Troublemaker only worked at HD resolution 1920×1080, which is almost 2k resolution.” The reason it isn’t exactly 2k resolution is that the Sony F950 and other HD cameras are ATSC standard at 1080p. (The p stands for progressive, which means no temporal interlace artifacts as with 1080i television images.) Standard 2k film scans are 2048×1556. Does that mean HD sports less resolution? Not really. By the time an audio track is added to the edge, the 35mm image is typically reduced to 1828 pixels wide. By the time 1828 is cropped to 1.85:1 aspect, it’s just 988 pixels tall.

The Digital Cinema Society (DigitalCinemaSociety.org) recently met in a session titled “HD 4:4:4–Where do we put it?” The new generation of HD cameras produce gorgeous images, but data storage is a challenge. “Sony waited until they had a complete system including the HD-CAM SR recorder before bringing the HDC-F950 to market,” notes Sony marketing manager Rick Harding. Sin City used the SRW-5000 HD-CAM SR studio deck, as did the new Star Wars. This deck uses MPEG-4 studio profile compression at 440mbs with a compression ration of about 4:1. (The 880mbs Sony SRW-1/SRP-1 HD-CAM SR field recorder was not yet available.) For comparison, DV is 25mbs and Sony’s new MPEG-2 IMX format is 50mbs. At 24fps, the longest HD-CAM SR tape lasts 50 minutes.

Surprisingly, the DI revolution is both advancing and holding back the digital cinema revolution. When you’re already digital with DI, it seems logical to go digital through to projection. At IVC High Definition Data Center in Burbank, color grading decisions for feature films such as Ice Age are made using color-accurate HD digital projection. The technology is ready in the screening room, but digital cinema deployment is slow because of high costs equipping theaters and concerns of obsolescence in rapidly evolving projection technology.

What’s ironic is the tremendous improvement DI is bringing to film prints, making a proven technology look much better. “Major films are first-generation prints from DI on polyester film stock that wears like iron,” notes IVC marketing VP Dick Millais. HD and digital intermediate are producing much better film images than ever, whether projected digitally or from 35mm film.