By Patrick Z. McGavin

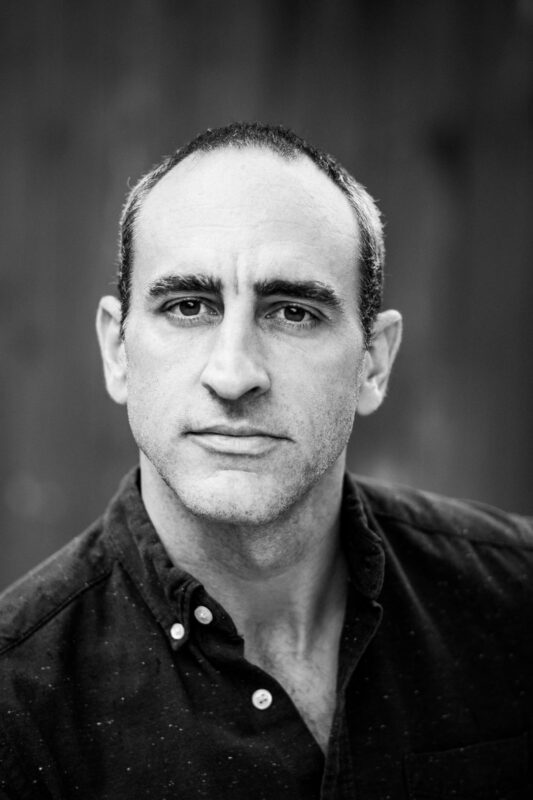

The New York-based editor Ron Patane, ACE, is a key figure in American independent cinema, with projects such as Derek Cianfrance’s “Blue Valentine” (2010) and J.C. Chandor’s “A Most Violent Year” (2014).

His newest film, “Till,” is a powerful exploration of the young life and tragic death of Emmett Till, the Chicago teenager whose lynching in Mississippi in 1955 galvanized the Civil Rights Movement.

Featuring an extraordinary lead performance by Danielle Deadwyler as Emmett’s mother, “Till” is directed by Chinonye Chukwu. Her previous film, “Clemency” (2019), won the top dramatic prize at Sundance. “Till” had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival earlier this month and was released in the U.S. a couple weeks later.

CineMontage: How did you first become involved with the film?

Ron Patane: I got the script from my agent. I thought it was really powerful. I read a fair number of scripts. I don’t always have an emotional reaction to them. I really responded to the script.

I had a call with the director Chinonye Chukwu. I really liked her previous film, “Clemency.” I could tell whoever made that film had a very specific point of view. Chinonye is very intense, and I think she wanted to make sure the editor she got involved with was going to be the right person. I felt the best way I could help the world was to use my talent and ability to do what I do, and tell the right kind of stories.

CineMontage: Did you have many discussions about how Chinonye wanted the movie to flow?

Ron Patane: We didn’t have many discussions that I can remember prior to the shoot, or during the shoot, about how the story should be told. It’s obviously in the script, and the decisions Chinonye made about point of view is a very strong vision.

That combined with the way the film was shot, a lot of very elegant shots with performances that are really sustained, you can hold shots. That’s part of the job I like when the footage is coming in, and not knowing what that world is going to be like. It’s revealing itself day after day as they are shooting. I’m trying to construct the scenes, which at that point are disconnected from the rest of the movie.

You are discovering the movie as it is being shot. I have certain instincts that I think align with Chinonye. The way she was shooting the film made a lot of sense to me, with point of view and the camera, along with cinematographer Bobby Bukowski.

It came together pretty naturally, but I think what I was doing was helping Chinonye with a point of view and going deeper with it. A historical film like this, there are a lot of angles to come from, and there is a lot of context. You could see another version of this film that had a lot of archival material, maybe scenes where Mamie is not there, or circumstances around the story. A lot of the decision-making was about what we weren’t going to show.

CineMontage: Chinonye Chukwu made that exact point at the New York Film festival press conference. She did not want to depict violence against Black bodies. How did that impact your work?

Ron Patane: Because she knew that, they didn’t really shoot that much of that kind of thing, but there was some of what happened when he was abducted and his eventual death. If we are going to do this, it should be done the most thorough way possible. Because the story is really Mamie’s, the point of view should really be hers. Once he is taken and abducted, just as the world experienced it, you should not really see him again. There is no reason for us to have this privileged point of view.

The film is more powerful for not showing that because it feels more like Mamie’s experience. We figured those things out pretty quickly. It was a matter of trying different things. My instinct was telling me pretty quickly to go further down that path that Chinonye had already laid out. We don’t want to see that at all. The film was not meant to be a history lesson. It was meant to be an emotional experience.

CineMontage: The opening moment reveals both a mother’s love for her son but also a sense of tragic foreboding in the change of her facial expression.

Ron Patane: It was interesting—it’s in the movie—that Mamie had some worry that is typical but also like a sixth sense. I think it’s also typical of the way a mother would worry about her child, especially in that situation, a Black boy from Chicago going down to Mississippi, a world that he doesn’t understand.

She wanted him to have a normal childhood, and not have the realities of the world on his mind. That innocence is probably a part of what happened. We know the story, so we know where it’s going. It’s a great dramatic thing to have in the story. She knows what could potentially happen. She has this feeling she can’t quite shake.

CineMontage: The early scene at the Chicago department store is mirrored by the fateful encounter at the Mississippi grocery store.

Ron Patane: It’s the difference between the North and South. That first scene is setting the tone, because there is not a lot of white perspective in the film. That scene is showing how things are operating in the North versus the South, and it’s not really that different, and what Mamie has to navigate in her world, and what she is protecting him from. It also sets up his naïveté a bit.

CineMontage: You have two fantastic actors at the center with Danielle Deadwyler and Jalyn Hall. What did you see as the most crucial emotional part of their relationship?

Ron Patane: I think Jalyn did a great job of showing the innocence and the vibrancy of Emmett as a charismatic young kid. I’ve had the good fortune of cutting performances by many great actors in my career. I could tell from day one, take one, Danielle was so focused and committed. That is an opportunity to let the cinema do the talking. We knew at any time we could be on Danielle—that would hold the screen.

There is no flashy editing going on, it’s about the strength of the camera and the performances doing the work. When I saw that in the footage, that was exciting. I know that we can build a really elegant film out of this. That kind of filmmaking, where every shot has a purpose and a meaning, really speaks to me.

CineMontage: In the aftermath of the tragedy, the second half is about capturing an absence.

Ron Patane: It is also about Mamie’s refusal to just let it be an absence. She turns it into something more. It could have been just that. There are moments when it is that, putting on the song on the record player over and over. I think how she transforms the absence into a presence, specifically the presence of the body, and something physical and direct. It’s not metaphorical, or a gesture. It’s tangibly real, and a big part of the power. Absence and presence are like two sides of the same coin. He lives within her.

CineMontage: Did you feel pressure at all given the long production gestation and capturing such a seminal moment in the Civil Rights Movement?

Ron Patane: There is a responsibility to do justice to a story that is very important, to the country, to the Black community. I wondered if I was the right person to help tell the story. I felt I connected to the story, and presented myself as being willing and up to doing it.

I put pressure on myself with every job. This is a culturally significant film, and that’s why I wanted to do it. Working with a new director I haven’t worked with before—a Black female director who has very strong opinions—was also exciting. Everytime I step into a thing with another director, I have to regain their trust.

Of course, I’m aware of the fact I’m a middle-aged, white male editing the Emmett Till story. Chinonye was also aware of that. We talked about that. It was about us coming together, and my gaining her trust. People pretty quickly realize that there is nothing else I am trying to do except make the best movie possible out of the material. They know they have an ally. Chinonye is a very strong personality, a strong director, and that protects me so that I can do exactly that.

CineMontage: With Chinonye Chukwu and previously Derek Cianfrance and J.C. Chandor, you have been most closely associated with independent directors who come out of Sundance. Is that the kind of filmmaker you prefer?

Ron Patane: I just like to work with directors who have a point of view, a thing that they do. Directors like Derek, J.C., and Chinonye, you can tell right away this is a film for them. They have their own point of view on the world and life, and that helps me because you understand what they’re trying to do. It shields me—whether it’s the politics or whatever—that I can do the best I can, with what I think is the best version.

My job is always to serve the director’s vision. That’s how I always think about it. I work for the director. That’s the person I have the closest relationship with. The way I want to work is to serve their version to make the best version they are trying to make. The strongest directors let you do that because you don’t have to worry about anything else.

CineMontage: Did you go to film school?

Ron Patane: I didn’t go to film school. I grew up in Connecticut. I was a philosophy major. I was interested in abstract, intellectual stuff. As I made my way through college, I had interest in film, and also music, theater, literature, photography, all of these different things. If I worked making films, they have all of those. This is what I should do, because I could actually do all of them.

Being an editor suits my personality. I’m a bit more of an introvert. I’m very happy to be hyper-focused on something, in a room by myself. I feel like I made the right decisions along the way to end up where I should have ended up. I’m perfectly happy to be working in anonymity. You have so much control over the film — that is a sweet spot to be in.

Patrick Z. McGavin is a Chicago writer and cultural journalist. He maintains the blog “Shadows and Dreams” (www.patrickzmcgavin.substack.com).