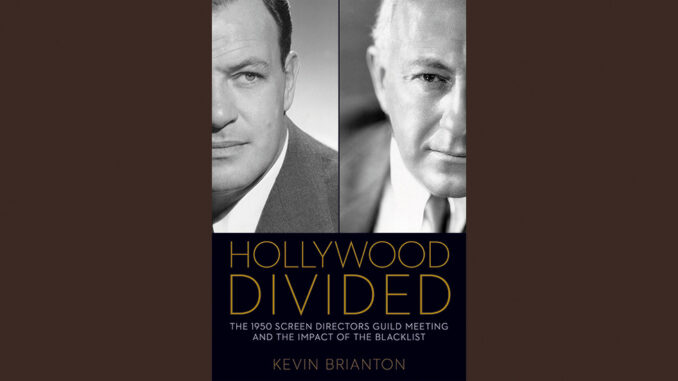

Hollywood Divided: The 1950 Screen Directors Guild Meeting and the Impact of the Blacklist

by Kevin Brianton

University Press of Kentucky, 2016

Hardcover, 174 pages, $45.00

ISBN # 978-0-8131-6892-0

by Betsy A. McLane

The blacklisting of Communists, former Communists, union supporters, socialists and people whose only agenda was to create films was a fact of life in the entertainment industry during the 1950s and 1960s. Few of the thousands directly affected by the tumult remain alive today, so it has been left to old memoirs and interviews, and to historians of every stripe, to repeat and interpret what has become ingrained Hollywood legend. And as longtime character actor Carlton Young, playing the town’s headline-grabbing newspaperman in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence (1962), says in a classic line to Jimmy Stewart, “When the legend becomes the fact, print the legend.”

The October 22, 1950 meeting of the Screen Directors Guild (the West Coast predecessor of the DGA) can still provoke emotion. Its legend features Ford’s much-(mis)quoted statement, “My name is John Ford. I make Westerns,” and a belief that he then brought common sense to the heated gathering. Kevin Brianton untangles this and other myths in Hollywood Divided: The 1950 Screen Directors Guild Meeting and the Impact of the Blacklist.

It is far beyond the scope of this review to detail the many ins and outs of the Blacklist, or even all the events surrounding that contentious meeting; best to leave the latter to Brianton’s scrupulously thorough research. He is an Australian academic who brings a dispassionate outsider’s view to Hollywood’s company-town lore. He religiously cites original sources, often pointing out discrepancies, such as those between an account “as told to” a biographer and an FBI memo.

Evident in every page are the hours Brianton must have spent pouring through the Joseph Mankiewicz papers at the Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills and at Harold B. Young Library at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, where the Cecil B. DeMille papers are archived. Brianton also references — and challenges — virtually every published source that mentions that infamous meeting, including such seminal works as Peter Bogdanovich’s 1978 book, John Ford, and Kevin Brownlow’s 2004 documentary, Cecil B. DeMille, An American Epic.

The SDG meeting took place amid growing anti-Communist hysteria. As early as 1947, 30 national and international unions representing various industries instituted loyalty oaths — a direct result of the Taft-Hartley Act, passed after much resistance from labor leaders and a veto from President Harry S. Truman. Taft-Hartley did away with closed shops and required all union officers, but not rank and file, to sign loyalty oaths. Brianton points out that in 1948, the Screen Writers Guild elected 20 anti-Communist individuals to its 21-member board, while the Screen Actors Guild introduced its loyalty oath for officers in January 1949.

IATSE followed a different route, not explored in Hollywood Divided. Roy Brewer, IATSE West Coast Representative from 1945 to 1953, oversaw what were called “clearances.” Brewer worked through the Motion Picture Industry Council, of which he was a founder, and could clear IA members who appeared on studio black- or graylists. MPIC was formed by 10 groups that included producers, guilds and unions. Its mandate was to promote better public relations for the industry, and it supported lobbying against censorship, trade barriers (Great Britain planned to encourage the development of its film industry by imposing a steep tax on American movies) and charges of anti-Americanism. The council announced the following goals in March 1949:

- Bring the “Communist problem” in Hollywood to the attention of all studio executives,

- Publicize the efforts of the industry to purge itself of “subversives,”

- “Clear” repentant Communists for employment, and

- Criticize all House Un-American Committee witnesses who refused to cooperate with the committee.

If they agreed to write letters explaining their political affiliations, and to apologize for them, and if Brewer felt the individuals were sincere, he would send the letters on to the appropriate people (per Larry Ceplair, co-author of The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960). The Screen Actors Guild, under presidents Robert Montgomery, George Murphy and Ronald Reagan, took a similar route.

For the Motion Picture Editors Guild, this tactic seems to have been largely successful in keeping members employed. Few appeared on the black- or graylists, perhaps because they were not as politically active as writers, actors or directors, or perhaps because post-production people were less visible targets. An exception was blacklisted, New York-based Carl Lerner — a charter member of the East Coast Editors Guild, IATSE Local 771 — but there was little political hay to be made from accusing even the best editors of the day.

The second chairman of MPIC was DeMille, then at the peak of his second round of immense Hollywood power. He is the most contemptuous character in Brianton’s story, except for FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, to whom DeMille reported for years, offering “information concerning the activities of Guild members whom he believes may be Communist Party members or Communist Party sympathizers.”

There were various, often shifting factions within the SDG. One was led by 69-year-old arch-conservative DeMille, who had railed against “unionism” at the Guild’s first organizational meeting 14 years earlier. Although never guild president, he gained control based on his very long record of film successes, by getting like-minded members elected to the board, and through the sheer force of his personality.

Hollywood Divided is a work of important scholarship, yet it is plainspoken in a way that might have pleased even Ford, a man not much known for being approving. He was only one of the many SDG members who met for seven hours that October evening at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Among them were former editors Robert Wise, Dorothy Arzner, Edward Dymtryk, John Sturges and Robert Parrish, as well as key directors such as guild president Joseph Mankiewicz, John Huston, Frank Capra, Billy Wilder, Rouben Mamoulian, King Vidor and George Stevens.

Arguments about instituting a loyalty oath was only part of the October 22 agenda, although at the previous August board meeting, DeMille had engineered a plan requiring all members to go on record when he orchestrated a “signed ballot,” one that did away with anonymity. Any member who did not vote yes would be seen to oppose the oath; it passed 574-14. Mankiewicz was on vacation in Europe at the time, after working on All About Eve (1950), and knew nothing about this.

With Mankiewicz back at the next board meeting, the oath requirement was discussed, and it remained in place. However, Daily Variety reported that Mankiewicz refused to sign, and that a “bitter debate” divided the guild. No one knows who fed this story to Variety, but DeMille assumed it was Mankiewicz, which the latter denied. DeMille was furious at this public challenge to his power and, as Brianton writes, “He snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.”

More strife followed, as DeMille tried to oust Mankiewicz, whom he had personally nominated as SDG president. The outrageous conduct of DeMille and his supporters intensified as the guild’s executive secretary was pulled into the fray, and a ballot to recall Mankiewicz was rushed to the membership list by motorcycle messengers. In an astonishing display of hubris, 50 to 55 Guild members who were potential Mankiewicz supporters were intentionally left off the list. This insult is carefully explained by Brianton, as is the resulting October 22 full membership meeting.

There, as DeMille spoke, the mood became uproarious, and Brianton captures its intensity by heavily citing the official transcript. (The DGA later sealed the transcript and, although it has since become available, the only version accessible for some years was Mankiewicz’s heavily annotated copy.) DeMille came prepared with his usual thoroughness, expecting to hold sway. He apparently saw the fight as one to preserve American conservatism and guild unity. Speaking of those 20-odd members who signed a petition to undo the Mankiewicz recall, he railed, “Is it their object to split this Guild wide open so that The Daily Worker and Pravda can gloat over the spectacle?”

DeMille was eventually cowed into presenting a motion to repeal the recall, but that did not end the rancor. Members continued to speak out against him and it seemed as if DeMille was going to be expelled from the board. It was then that Ford, who had remained silent, rose, identifying himself to the stenographer. According to the transcript, his actual words were, “My name is John Ford. I am a director of Westerns.” Apparently some chuckled, as Ford (another guild founder) was far more than a director of Westerns, although at the time he was working on Rio Grande (1950). Brianton characterizes Ford’s speech as “rambling, jumping from one topic to another.”

According to the author, “Having made it clear that he supported Mankiewicz and was no fan of DeMille’s loyalty oath,” Ford then proceeded to speak emphatically in defense of DeMille with the result that — in Brianton’s estimation — “Without Ford’s intervention, it seems unlikely DeMille could have survived the meeting.” Ford’s solution was to suggest that the entire board resign, thus saving face for DeMille. This eventually transpired, and a new board took office, with Mankiewicz remaining as president. Ford sent DeMille a letter of apology the following day.

SDG members did vote to sign a voluntary loyalty oath. Brianton unfortunately does not reprint that document, but Article III, Section H of the guild’s constitution required all members to swear to an oath reading:

“I am not a member of the Communist Party or affiliated with such party, and I do not believe in, and I am not a member [sic] nor do I support any organization that believes in or teaches the overthrow of the United States government by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional methods.”

The book’s flaws underscore its strength as an outsider’s assessment. Brianton does not seem to fully grasp how terrifyingly vital Daily Variety, “the Bible of Showbiz,” was to economic and social life in Hollywood. The Twitter of its day, careers could be made or destroyed in its pages — even when those pages were sometimes only reprints of publicity releases. DeMille’s blinding anger, rising from the article that questioned his power and control, makes sense when one understands that every day, those in the industry read in the trade papers what was understood to often be “fake news.”

Hollywood Divided cuts through the conflicting sentimentality and rancor that still surround the Blacklist era. By citing original documents and comparing conflicting stories, Brianton demonstrates how reasoned scholarship offers ways to make sense of seemingly overwhelming political confusion.

Some 67 years after the 1950 Screen Directors Guild meeting, the US is again a nation torn by partisanship and fear. DeMille’s rallying cry of “right to work” is heard loudly, and many devoted Americans find their patriotism questioned. Reading this book is a reminder that the country has found ways to seek truth, even in Hollywood, where it is far more comforting to “print the legend.”

(Writer’s note: Thanks to Jeff Burman for information about how IATSE dealt with the black- and graylists.)