by Barbara Pokras, ACE

I was lost. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. It was the early 1960s and I drifted in and out of college. I was on my own in Los Angeles, 3,000 miles from home. I lived in a ramshackle hippie house in the Hollywood Hills, took a sales job at the May Company, and unwittingly found myself on the fast track toward an accidental career in fashion merchandising. After work, I collaborated on writing projects with my ditzy, talented neighbor, LuAnne.

Whenever I could, I escaped to San Francisco’s North Beach, my spiritual home. It was easy to get there. At that time, it was possible to deliver a car from Los Angeles to San Francisco and even get paid a small pittance. Sometimes I went alone, and other times with my friend Victoria, a kindred spirit. This time, I was alone. I was looking for something to fill my life and I found it, quite by accident, on a third-floor walk-up “screening room,” with a lone bridge chair and a pull-down 16mm screen. I was the only customer. It was a 1959 presentation of all three films of The Apu Trilogy. I was enthralled and watched all three films at one sitting. (Twenty years after the original negative was destroyed by fire, Criterion Editions undertook a meticulous restoration.)

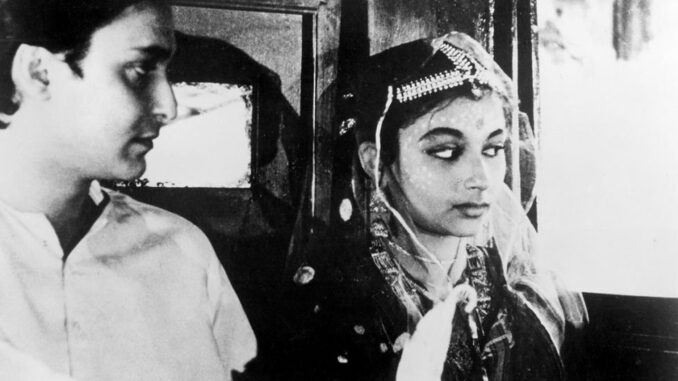

Sony Pictures Classics/Photofest

I’ve always loved movies. As a child, I imagined someone was following me around making a movie of my life. My first movie experience was a double feature — two cowboy movies. Mesmerized by the first, I turned and faced the back of the theatre for the entire second feature. I just didn’t want to dilute the memory. Maybe that’s why I’m a “close” sitter. Third row center suits me fine. I want to be pulled into the screen.

But it was director Satyajit Ray who changed my life by encapsulating whole generations into an epic story running just under six hours. It spoke to the universality of humankind with remarkable images and sounds. I walked away profoundly moved and said to myself, “This is what I want to do with my life.”

The Apu Trilogy chronicles the lives of young Apu and his family. Startling montages never impede the narrative. Trains and doorways are all rife with meaning. Each chapter brings with it Ravi Shankar’s alternately joyous and mournful ragas, underpinning and supporting indelible images and sometimes replacing dialogue.

The first chapter, Pather Panchali (1956), set in the 1920s rural India, introduces us to Apu’s older sister — mischievous, light-fingered Durga — caught stealing a neighbor’s fruit. We meet Sarbajaya, a proud and stoic mother, and father Harihar, a dreamer eking out a meager living as a traveling priest. Stooped and barely able to ambulate, “Auntie,” an ancient crone, navigates between the mother’s resentment and Durga’s adoration. But it is through the enormous, ever-observant eyes of Apu that we gain access to a world both distant and universal.

A train becomes a conveyance to a life beyond the simple confines of rural life. Anyone who was once a child will understand the excitement of the traveling sweets salesman (think Good Humor), or the itinerant theatre troupe (think circus). A terrible storm seals Durga’s fate, and Apu’s discovery of her secret propels this chapter toward its conclusion. The ancestral home, battered by the storm, once again reverts to nature.

In Aparajito (1957), Ray moves us beyond simple village life to the holy city of Benares, where Harihar earns a living performing rituals at the foot of the Ganges. Having suffered the loss of their village home, the dream of a better life is nearly at hand when the sudden death of Harihar leaves mother and son nearly penniless. Sarbajaya takes a job in a household in the countryside, and it is here that Apu discovers his insatiable love of learning. In an instant, Apu catapults from child to a gaunt young man — nearly as tall as his father. Sarbajaya understands that the more worldly and studious Apu becomes, the more estranged he will be from her.

In the third of the trilogy, The World of Apu (1959), Apu, now grown, struggles to be a writer. He marries happily, quite by accident, but his wife dies in childbirth. Grief-stricken and bitter, Apu rejects his son. Tormented, he wanders, aimlessly struggling to assume the responsibility of fatherhood.

The night I left that tiny screening room, I had a dream and in it I said to my writing partner, “I don’t write with words anymore, I write with pictures and sound.” Nothing satisfies that definition more than editing. I had never met an editor and I had no family in the film business. So powerful was that dream that shortly thereafter, I left my retail job and with a little help from my sister and mother, went back to school and earned my degree in cinema. I never looked back. The lesson? Follow your dreams.