by Walter Hess

In 1960, after college, the army, UCLA film school, paying my dues as a can-carrying apprentice and assisting (mostly on commercials, but also some documentaries and industrials), I received a call from the editor Peggy Lawson, who said, “Sidney needs an assistant; I’m recommending you.” Wow — a documentary series on ABC, Winston Churchill: The Valiant Years (1960-61). And even greater was the fact that I was going to work with Sidney Meyers. Toward the end of the series, Sidney had to leave for another job. “I’m scheduled for one more piece,” he told me. “I’ve told them you’re going to do it.” Working with Sidney then, and later, changed my life.

Many years later, I found some remarks by the novelist and critic Clancy Sigal, who had once been an assistant to Sidney during the making of his great film The Quiet One (1948). Sigal’s description of Sidney — which he wrote in a letter to Sidney’s wife Edna after the editor’s passing — felt right. Sigal knew what I was to get to know.

“He had time to spend with me, a film newcomer, and we spent many afternoons discussing life, art and politics, sometimes just horsing around, and occasionally he let me watch him cut,” Sigal wrote. “He was…a master. I’d never before seen such playful competence. At first, it was terribly confusing to me because I never knew what was supposed to be serious and what was a joke. Later, I learned that this was Sidney’s method of instruction, to break down the distinction…

I always felt sure of Sidney when he was talking about movies or pictures or books, sure that he had felt what he was saying… He made me laugh more than almost anyone. The jokes were good; they were part of his playfulness, the artist’s kind of playfulness, which was very dear to my heart.”

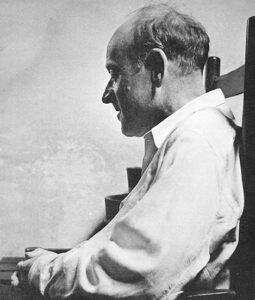

Sidney Meyers was born on March 9, 1906 to a family of Jewish immigrants in a section of New York now known as East Harlem. The family was poor and he remembered his mother, every winter, buying a 100-pound sack of potatoes, which she stored in a closet “just in case.”

From an early age he displayed a keen interest in music. He learned the violin sufficiently so that at age 21 he was invited to join the Cincinnati Symphony, with which he remained for several years, by its conductor, Fritz Reiner. Then, during the early years of the Great Depression he frequently played with an orchestra subsidized by the WPA (Works Progress Administration).

By 1932, to expand his longstanding interest in photography, Sidney became involved with the Workers Film and Photo League, which was interested in, among other things, using the movie camera to document social conditions for a working-class audience. Since he was still working as a musician, he could not go out with film crews on his rehearsal days, so more and more of his film work concentrated on the editing table and the soundtrack.

In early 1935, his writing career began. He became a film critic and editor for New Theatre and other periodicals, choosing “Robert Stebbins” as a pseudonym to protect his other jobs.By1936, he left music for film making.

Through the league, and his literary ventures, Sidney became acquainted with a large number of talented people who were to become major contributors to both the American documentary movement and to theatrical film: editors/directors Jay Leyda, Leo Hurwitz and Irving Lerner; cinematographers/directors Ralph Steiner, Paul Strand and Willard Van Dyke; and writer/ director Ben Maddow.

By 1937, a new organization had come into existence: Frontier Films. Frontier was staffed by many of the people who had come through the league and Nykino (New York Kino). Frontier, while on the left in its political orientation, was independent of outside influences in that it raised its own funds for its own projects. The idea was to work cooperatively on each project. The writer, director, editor and cinematographer were all to collaborate at each stage of the undertaking.

Sidney’s name led the credits on an extraordinary set of documentaries by Frontier, whose makers included Lerner, Maddow and Leyda. China Strikes Back (1937) was composed of raw newsreel footage (smuggled out of China) portraying the life of the Eight Route Army, a military unit under the command of the Chinese Communist Party. People of the Cumberland (1937) was a combination of re-enacted drama and documentary footage that showed how a poverty-stricken community struggles to become an efficient, productive society through education and the labor movement. Here, Elia Kazan was an assistant to directors Sidney, Leyda and William Watts.

For the 1939 World’s Fair, Chrysler Motors sponsored Frontier to create The History and Romance of Transportation entirely out of stock footage. White Flood, completed in 1940, is another Frontier film that had to be made in the cutting room. This film is now remembered for its beautiful footage and the very original music score by Hanns Eisler. In each, Sidney is credited with both editing and writing.

With the approach of World War II, many of the participants in Frontier drifted away. After Pearl Harbor, the British Ministry of Information gave Sidney the responsibility for preparing its films for American audiences, and eventually the US Office of War Information employed his talents to plan and supervise its films.

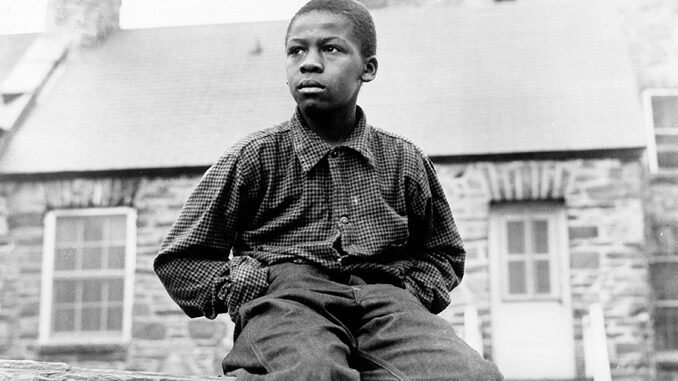

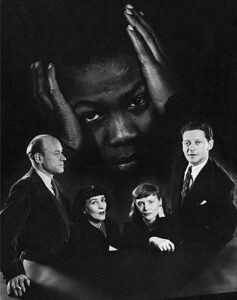

The two major films for which Sidney had a significant share of responsibility — and on which much of his reputation rests — were The Quiet One and The Savage Eye (1960). Both were independently made, outside the ambit of Hollywood studios. The Quiet One was the first major American film to use a black youth as its protagonist and one of the first non-fiction films to deal with issues of racism and black poverty in America. Meyers directed and edited, while the camera was in the hands of Richard Bagley and the marvelous still photographer Helen Levitt. Janice Loeb produced. When their film was nominated for an Oscar for Best Writing (Story and Screenplay), Sidney insisted that all four names were to be recorded as authors. When the Academy refused, Sidney declined the nomination. All but Bagley were ultimately credited. The film was also nominated for Best Documentary (Feature).

The Savage Eye began with Maddow’s idea of attempting to see Los Angeles as the painter and printmaker William Hogarth might see it. As in The Quiet One, documentary footage was braided into the narrative. This challenge to “penetrate the dark and tawdry side of 1950’s urban life,” as Maddow described it, took nine years to complete. It received raves in Europe, while some New York critics considered it “cold,” “heartless” and “inhuman.” When one of the critics gathered the film’s makers around a lunch table, Sidney felt obliged to react: “If you despise humanity, you wouldn’t bother with it. That’s true of all satirists. You take a shellacking in life before you’re through with it, but there’s a common bond of suffering.”

Sidney died December 4, 1969 at age 63. In a stirring remembrance, written after Sidney’s memorial service, Leyda recounted Sidney’s post-war years, and his struggle for a livelihood: “What would he have said to the crowded funeral parlor that grim Sunday afternoon? What were they thinking of him? If they thought of him as a filmmaker, what were the films they thought of as his? The Quiet One? That’s all? His value as a filmmaker spread so much further than ‘credits.’ What did ‘edited by’ really mean in his case? Most of the people sitting there…knew that Sidney had helped them more than they could ever admit to themselves…

“We all knew that Sidney loved films so much, and some filmmakers too, that we could count on his advice whenever we needed it,” Leyda continued. “If he found himself bending over a Moviola, with the loose or shapeless structure of a friend’s film stumbling through it, he knew this was where he belonged. Sometimes a director was sensible enough to bring Sidney in before the film was shot, or during the shooting, and call this actual artistic supervision of the film ‘editing.’”

Leyda concluded: “If it was a…network or business that wanted his help, he asked for a proper salary, but usually settled for minimum. The livelihood of his working years came from places like CBS, NBC, Monsanto, the Girl Scouts and the Ford Motor Company, but always there were promises, promises to direct from producers that were never consummated.”

At Sidney’s memorial service, my friend Manny Kirchheimer spoke of the essential Sidney so many of us knew and loved. He spoke for so many of us who began our professional lives under Sidney’s care and tutelage: “Close to when I first met him — I was 21 working at my first job in film — he told me of the time he was asked by the distributor to cut down Rashômon for American audiences. Sidney said, ‘I told him it’s the work of a master — I wouldn’t touch it.’ And then he impishly added, ‘And I needed the money, too.’ That comes back to me now for good reason. It meant you ‘have dignity.’

“Another time on a very hot, not air-conditioned day,” Kirchheimer added, “standing on a plush, red carpet left over from when the cutting room belonged to a high- fashion milliner, Sidney was rewinding bare- armed in a sleeveless undershirt, and wearing a pinched brown hat. ‘Why the hat, Sid?’ I asked. ‘That’s to let them know I’m not here to stay.’ That was funny. What it meant to me was: Be your own man. Don’t let them seduce you with money, praise, comfort.”

Kirchheimer continued his tribute: “One lunch hour of a particularly beautiful day… we were walking on the avenue when Sidney said, ‘Look at the people; don’t they look great with the sun on their faces?’ And realizing that the sun was not on his face, he suddenly ran ahead, turned around into the sun, floated back towards me, and asked, ‘Did I look great too?’ I was 21 and wanted everybody to know I was with the great Sidney Meyers — the man who made The Quiet One — and he was acting as if he was my friend.

“Years later, a good friend and I were working on a television science series for CBS and Sidney came to visit us in the cutting room. ‘It’s good,’ he said, ‘you guys are working. How do you get jobs? I’m looking for work.’ I was ashamed. ‘Your trouble,’ I said, ‘is you’re over-qualified. People think you’re too good for the junk they have. They’re afraid to ask you.’ He said, ‘I’ll put an ad in Variety: SIDNEY MEYERS HAS LOST HALF HIS SKILL.’ Later, when Walter Hess heard the story, he told me, ‘I’ll put an ad right under it: I HAVE FOUND HALF OF SIDNEY’S SKILL.’

“That wish spoke for all of us,” Kirchheimer concluded. “We were the lucky ones; we who knew him, who were privileged to share him. And maybe just because he was so vulnerable, so human, and because he didn’t give to us in such a way that we felt we owed him something, maybe that’s why we loved him so and why we took him for granted. And maybe that’s why it took so long for me to realize why he was so important to me.”

In Films on the Left: American Documentary Film from 1931 to 1942 (1981), author William Alexander writes of the time when Sidney was engaged with the Film and Photo League and Frontier Films, but it is a judgment that might characterize his whole career: “It is possible that among this very talented group of artists, it was Meyers who was the most talented. Many… believe this to be the case. A man of great wit and character, an assiduous reader who was highly skilled in several arts, a man who could never be doctrinaire yet whose politics and loyalties were firm, a man who would edge into the background rather than seek recognition, he was greatly loved and admired. It is almost impossible to find a negative word about him…”