by Debra Kaufman

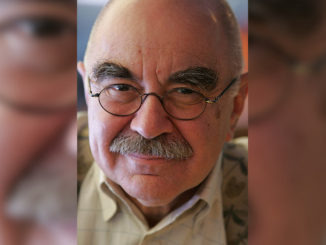

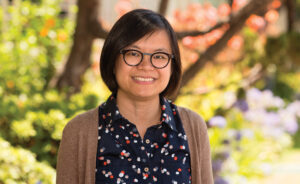

portraits by Martin Cohen

In 1973, the tennis court became an unlikely showcase for the heated battle of feminists and their foes. Bobby Riggs, a top tennis player in the 1940s and showman extraordinaire, challenged top female tennis players to try to beat him on the court. Top-ranking Margaret Court took the challenge and lost, leading Billy Jean King — who had previously turned down Riggs’ personal challenge — to step in and prove him wrong.

Fox Searchlight Pictures

Some 90 million people worldwide watched the match, held in the Houston Astrodome and billed as the “Battle of the Sexes.” The event was more circus than tennis match, as both players were brought in ringed by scantily clad attendants and the combatants exchanged pointed gifts (Riggs, sponsored by Sugar Daddy candy company, gave King an oversized lollipop, while she presented him with a piglet).

Now Battles of the Sexes, a Fox Searchlight picture directed by Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, starring Emma Stone and Steve Carell, shot by Linus Sandgren and edited by Pamela Martin, ACE, opens through Fox Searchlight September 22. Supervising sound editors Mildred Iatrou and Ai-Ling Lee — who was also sound designer and one of its re-recording mixers (with Doug Hemphill, CAS) — had previously worked on the 2012 Hitchcock with Martin, who invited them to interview for the film.

The sound editors, who enjoyed a great working relationship with Martin on Hitchcock, were also drawn to the film by a mutual appreciation of Dayton and Faris’ previous films Little Miss Sunshine (2006) and Ruby Sparks (2012). “Battle of the Sexes is not just a sports film, but one filled with many intimate moments and complex characters,” says Lee, who adds that she and her husband are also tennis fans.

Having worked as a team on five features, most recently 2016’s La La Land (which earned them an Oscar nomination for Best Sound Editing, as well as Best Sound Mixing for Lee), Iatrou and Lee read the script and began their research, including watching the original broadcast of the “Battle of the Sexes” event. “I was curious to see how the crowd reacted to the game, and how it built,” Lee says. “It was very unlike traditional tennis crowds that were very polite, with none of the yelling or whistling I heard on the broadcast. Women were cheering more for Billie Jean and the men for Bobby.” She took notes on some of the specific crowd noise, as fans called out to their favorite. “By the end, the audience became more vociferous and raucous as the match continued,” offers Iatrou. “I was able to direct the loop group actors to do the same, and imitated some of the call-outs verbatim.”

Photo by Chad Strawderman

The directors wanted the sound to be of the period, “but with more of a contemporary polish, while still sounding authentic. In terms of dialogue and ADR, they wanted it layered as in Robert Altman’s early films,” says Iatrou, who watched numerous Altman films as preparation. “Altman layered the dialogue in the foreground and background. So any time there was a group of actors in a scene, we would create foreground and background conversations by adding ADR and using production dialogue outtakes.”

Most of the dialogue in the film was production-recorded on the set, with ADR used to add additional dialogue. “Lisa Pinero did a great job as a production mixer; every actor was mic’d with a personal mic and sometimes a boom,” Iatrou states. “There were up to 13 production tracks in some scenes, and this was very useful to help achieve the layering of dialogue and a lively and naturalistic atmosphere. It was fun to add layer upon layer of sound.” The movie was edited and mixed in 7.1 surround sound.

To create authentic sound effects from the era, Lee bought several wooden and aluminum tennis rackets, strung them with the kind of gut strings used at that time, and then recorded all kinds of tennis ball hits. “It had a slightly different tone than present-day graphite,” she says. Because she often brings her recorder to sporting events, Lee already had a number of recordings of crowds. “It turns out my husband and I went to the US Open and recorded the tennis crowds, and I started building a library of sounds,” she adds. She also went to the Vermont Canyon tennis courts in Griffith Park. “We picked 2:00 p.m. on a hot summer day, because we figured not as many people would be out,” she says.

In addition to era-accurate tennis sounds, Lee also had to consider phones, cameras, televisions and more. “With all the reporters, we were trying to stay away from stereotypic camera sounds and use film camera sounds,” explains Lee. “We also had to pay attention to TVs with their clunky remote controls and high-pitch tones, and even sirens in the background when Bobby Riggs is in New York City.” At the airport, when the female tennis players gather around an old-fashioned personal TV screen, Lee not only had to create sounds of the game, commentary and audience coming from the small TV, but also sounds that convinced audiences they were in an airport.

Battle of the Sexes also features a kind of subliminal sound effect called AMSR (autonomous sensory meridian response). Dayton and Faris wanted that kind of effect when Billie Jean and hairstylist Marilyn are together for the first time, and their romantic feelings are ignited. “They wanted it to be close and intimate,” Lee says. “Once Jonathan mentioned AMSR, I began to research how to achieve that. In that scene, Marilyn is cutting Billie Jean’s hair, so I recorded the hair being cut and brushed, and the breathing, all very close up. It was hard to do because it’s typically a very quiet environment with a very close-up sound. We can’t do that with speakers, so I tried to improvise and record the sounds very close up and then, in the movie, if I could, slowly pan in the mix so you feel like it’s more in your head.”

Fox Searchlight Pictures

The film’s final tennis match was the movie’s most demanding sequence for both Lee and Iatrou. “All the matches have so many layers,” concedes Lee. “You have the girls, the commentators, the game, the crowds and the music. They’re tricky sequences and took a lot of finessing and prioritizing.” Some of the effects are subtle. For example, as Riggs leaves the hotel to go to the final match, at the last moment, his son Larry decides to stay at the hotel and watch it on TV. “The music has this ongoing beat to drive us forward, and I took the cue,” says Lee. “It’s a very tiny thing, but as Bobby is on the escalator, I built it to have this rhythmic, clunking sound, like marching forward with the game.”

Lee says she purposefully varied tennis hits in the match, adding subtleties to the audio that supported the match as it developed. “I would put hints on the strategy in the game,” she reveals. “Sometimes they’d lob and I’d cut in slices of tennis hits so you know when they want to hit far or close, as part of Billie Jean’s game plan in the match, since Bobby is so out of shape. As the match gets going, his feet are stomping more as he gets tired. The crowd builds into more of a frenzy, with call-outs here and there, to help spice it up. Then the crowd noises drop on the last match point, which helps build the tension.”

Courtesy of Chad Strawderman

For Iatrou, one of the challenges was that the directors wanted to use the original recording of the late sportscaster Howard Cosell’s commentary of the game. “Ordinarily, you’d use a sound-alike when the person is deceased or there’s no chance to bring him in,” she explains. “But they wanted the original recording, which was a mono mix on a stereo track. We looked for separate tracks but couldn’t find them.” Iatrou says they did a massive search for a sound-alike and did find someone who was “close and good, but not a perfect match…so we used him sparingly. The bulk of that is the real Howard Cosell from a videotape of the broadcast.”

What made it more difficult was that Iatrou had to seamlessly blend Cosell’s dialogue with that of actor Natalie Morales, who played co-host Rosie Casals. Iatrou points out that because they were mixing sounds of the original recording, they sought out the microphone used at the time, an Electro-Voice 635A, which they used to record Morales. “We used the mic for all the broadcast commentators,” says Iatrou, who notes that they found and purchased the microphone on Amazon.com.

When it came to replacing Rosie’s voice in the original video recording, according to Iatrou, “We spent more time mixing that in terms of pre-dubbing and mixing than anything else in the movie — and we tried so many different things.” Ultimately, what worked was noise reduction plug-in Isotope RX5 and EQ Match, the latter of which was used to make the EQ of the distressed, old recording of Howard Cosell dialogue match with the bits from the sound-alike. “And dialogue/music mixer Ron Bartlett spent a lot of time EQing the dialogue,” adds Iatrou.

Regarding the music and effects around those scenes, Lee reveals that they allowed her to create “the illusion of immersing the audience” in more of a surround environment. “Jon and Val wanted that to help sell it,” says Lee, who reports that she used reverb tool Altaverb as well as Avid’s EQ. “Early on, the women tennis players are playing in small games, and they slowly grew in size. By the time we get to the final match, the crowds are chaotic, and that’s when we used lots more of the surround, the spotted call-outs and some of the effects. I also used crowds from boxing matches; and in the mix, we played around with the perception of the size of the venue and crowd — like adding reverb to the call-outs, which gives the impression that the arena is a lot bigger.”

Lee received the score, composed by Nick Brittell, midway through post-production. “He did such a marvelous job,” she says. “His score lifted the film to another level. So I had his demo music and worked the effects and backgrounds with it.” Iatrou also credits the contributions of the small sound team for Battle of the Sexes, which, aside from the aforementioned mixers Hemphill, Pinero and Bartlett, included ADR editor Galen Goodpaster, Foley supervisor Jonathan Klein, sound effects editor Chris Diebold, dialogue editor David Butler and Foley artist Dan O’Connell.

Working with editor Martin was, again, a great experience for the sound editors. “Early in her career, Pam was a dialogue editor,” says Iatrou. “That really shows in her tracks. She also understands how much time is needed to prepare for a temp and makes sure we get new versions turned over in time. And during a temp, she knows what can wait for the final and what needs to be done immediately. She gets the big picture. She has a firsthand knowledge and good understanding of the sound process.”

Fox Searchlight Pictures

Lee offers, “Pam is very involved with sound as she is cutting the picture. For the first half of the post-production sound process, my office was down the hall from the building where she, Jon and Val were cutting the picture,” she says. “So I would review sounds with them, including Pam. She has a very good sense of what Jon and Val like, so if they weren’t available, I could have her review some sound, get feedback and exchange ideas. It was a really good workflow.”

Battle of the Sexes was an interesting combination of sounds that were most definitely of the period, but within an overall modern, immersive feel, according to Iatrou, who explains, “The directors wanted the audio to be this nice, rich soundtrack — but without calling attention to itself.

“If moviegoers watching the film feel that they’re in the time period and are drawn into the story because of how immersive the audio is, that was our goal,” she adds in conclusion.