by Paul Hirsch, ACE

The Droid Olympics could only have happened at the time and the place that they did.

When I heard the announcement in December that Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope Productions was closing after 35 years of operation in San Francisco, I thought back to a couple of special days I spent in the Bay area over 20 years ago. Although I was based in New York at that time, and had never lived and worked anywhere else, I edited three pictures in Marin County, California.

In 1969, Coppola and fellow producer/director George Lucas had set up editing facilities in Northern California in order to get away from the massive gravitational forces exerted by Hollywood and the studios. They were surrounded by a small community of like-minded filmmakers, among them Walter Murch, Matthew Robbins, Hal Barwood, Carrol Ballard, John Korty, Phil Kaufman, Michael Ritchie, Robert Dalva, Thelma Schoonmaker, Richard Chew and Marcia Lucas. There was a connection to New York, too, partly due to the fact that Coppola, Murch, Robbins and Dalva came from there, and partly due to the natural sympathy that these two regional outposts of the film industry shared, as communities of independent-minded cinema enthusiasts.

I was brought to Marin County in Fall 1976 to help out on a picture that had fallen behind schedule. It was entitled Star Wars. I arrived from New York, and immediately was beguiled by the physical beauty of the place with its rolling golden hills, and by the friendly and inclusive atmosphere that existed among these various film people. My wife Jane was pregnant with our first child, and we couldn’t have been greeted more warmly by the families there.

This was, after all, the late ‘70s. Watergate was only a couple of years behind us. The last chopper had left Saigon only 18 months earlier, and the counter-culture was alive and well in Marin at that time. San Francisco had been the locus of the Flower Power movement, and Marin was a center of Zen studies, hot tubs and alternative lifestyles. Although it is easy to make fun of all that now, there was a sweet and innocent aspect to much of this.

The friendly spirit of camaraderie and community combined with an excitement about the art and craft of film, reached its epitome for me in the event known as the Droid Olympics. There were actually three of them: one in 1978, one in 1980 and one in 1982. I missed the first of these, but was lucky enough to be there for the latter two, and they were among the most enjoyable memories I have of my days there.

The notion for these Olympics came from Murch, who was editing Apocalypse Now for Coppola in 1978, when the first event was held. According to him, “There was a lot of film—1,250,000 feet of workprint—with so much robotic reconstituting of trims, that the half-dozen assistants on the film started calling themselves ‘droids’ in honor of the robots in Star Wars, which had been released the year before.

“In June of ’78, my wife Aggie had put on a horse show for the local kids in Bolinas,” Murch continued. “And I was eyeing the ribbons and trophies when the idea came to me to throw a similar event for the assistant editors on Apocalypse, to celebrate their skills.”

These are all arcane abilities today, largely forgotten in the wake of the now 10-year-old digital revolution in the professional cutting room. The games were staged at times when there were enough feature films cutting in the area to supply teams to compete, usually four or five. There never was much of a film industry in San Francisco, and the activity ebbed and flowed. But when there were enough pictures working at the same time, the “Games” were held. In those days, editing crews ran from three or four assistants up to eight or more.

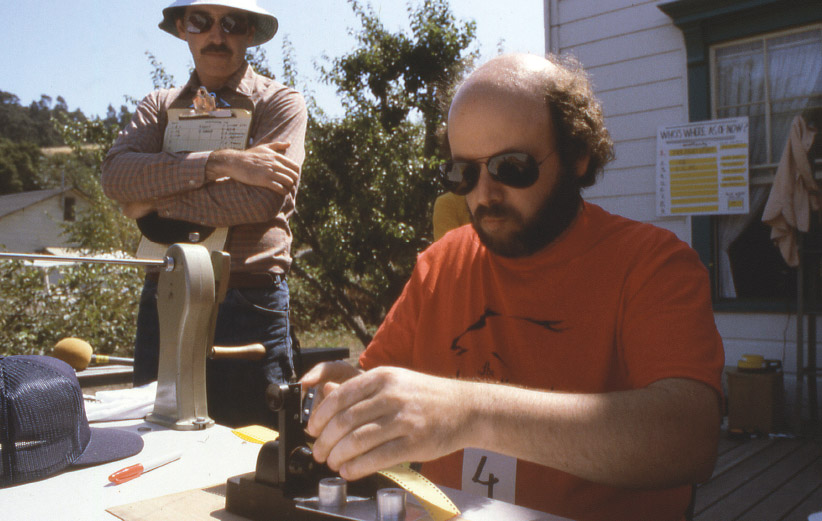

The site for the events was the Murch residence at Blackberry Farm in Bolinas, up the coast from the Golden Gate Bridge. The events were staged outdoors, in front of the house and on the porch, and there was a potluck lunch served. There were Moviolas, editing benches, synchronizers, splicers, racks and trim bins. Families came in groups to cheer the contestants on, and the day was spent outdoors (amazing for editors!) in a festive atmosphere of good-natured competition, with children and dogs running around in the glorious weather peculiar to that part of the world.

The idea was a Decathlon of editing skills, some were head to head competition, some were against the clock. The events were:

Speed Splicing

The challenge was to splice 10 eight-frame pieces of leader together, front and back, against the clock. The resulting single spliced piece of leader had to be able to run through a Moviola without tearing.

Demolition Rewinding

Starting with a 1,000-foot roll of picture and a 1,000-foot roll of track, you had to thread up the film onto take-up reels, put the start marks in a synchronizer, wind down as fast as possible to sync marks at the end, stop on that given frame and lock the synchronizer––all against the clock. One of the difficulties faced by contestants (which they never faced in their professional lives) was the wind, which made the very first step difficult.

Putting The Sync (Putting as in shotput)

This was the game that bored assistants always played during slow times on the job, spinning the synchronizer as hard as they could to see how high a number they could reach. At the 1982 games, the sync block had been worked on by some machinists at Industrial Light and Magic, and was so finely balanced and tuned that it would spin (seemingly) forever. Scores of more than 1,000 were not uncommon.

Veeder-Root Sharp Shoot

This event, named after a maker of counters, had contestants sitting blindfolded in front of a Moviola. The counter was set to zero, the motor was engaged and the competitors had a hand on the brake. The idea was to let go, count to yourself for 30 seconds, and hit the brake as close to 45 feet as you could. (In 1982, Dalva hit 45 feet and 3 frames and lost!)

These are all arcane abilities today, largely forgotten in the wake of the now 10-year-old digital revolution.

The Cornel Wilde Memorial Footage Guess

This was akin to guessing how many marbles in a jar. There was a roll of film, and you had to guess how long it was just by looking at it. (I won this one, and still have my Blue Ribbon.) According to Murch, “The event was named for Mr. Wilde because, when he was interviewing editors for his documentary about the making of Beach Red, he would quickly pull a reel of film out of the drawer of his desk, flash it before the startled interviewees (Robbins and Lucas among them) and ask how much film it contained.”

Bobbing for Smitchies

Against the clock, you had to find a two-frame “smitchie” in a trim bin, filled to overflowing, without dislodging the hanging strips of film. Some of the times were phenomenal: under one second. The reason was that the trims were rubber-banded to the pins, and people would simply reach in and grab the entire ball of film, throw it up in the air, and if you were lucky, the smitchie, the two-frame trim, would be lying at the bottom of the bin.

Worse Hand Anyway

This required winding 50 feet of yellow leader onto a three-inch plastic core, using only one hand, against the clock. If you were a righty, you used your left hand, if you were a lefty, you used your right hand, hence the name of the event. (If you lost, you could say, “Well, it was my worse hand, anyway.”) This was an exciting spectator event. The participants would line up on the porch, and the 50-foot yellow leaders would be extended out onto the grass in front of them. There were heats, since you could only do about eight people at a time. At the start, people would start furiously twisting their wrists, winding the film, and spectators lining the playing field could watch the film moving toward the porch, like runners in their respective lanes. Lots of cheering and rooting went on.

The idea was a Decathlon of editing skills, some were head to head competition, some were against the clock.

Trims and Outs Dash

In this one, you were loaded up with full trim boxes higher than your eyes, with your arms extended below, and then in groups of four, you had to run as fast as possible down the 50-yard gravel driveway without spilling any of the boxes. One producer, Tom Sternberg, with hubristic visions of victory dancing before his eyes, took a particularly spectacular fall.

Flanging

You had to wind handfuls of trims into rolls using the plate on the left side of a Moviola, without ripping or bending the film. This was a timed event and the clock didn’t stop until you got the roll off the Moviola The frequent difficulty for the enthusiastically inexperienced was that the film would get so tightly wound it would be almost impossible to get it off the flange.

Rack Arranging

This was a team event––the only one––although individual events were counted towards team totals. Four people on a team had to alphanumerically sort about 100 trim boxes jumbled in a heap, and put them on a rack in correct order against the clock.

All these skills are being slowly forgotten, and it’s unlikely there will ever be another Droid Olympics. But those days back then, out in the sun with fellow filmmakers competing and cheering and eating hotdogs and salads, were among the most enjoyable I have ever spent.