By Betsy A. McLane

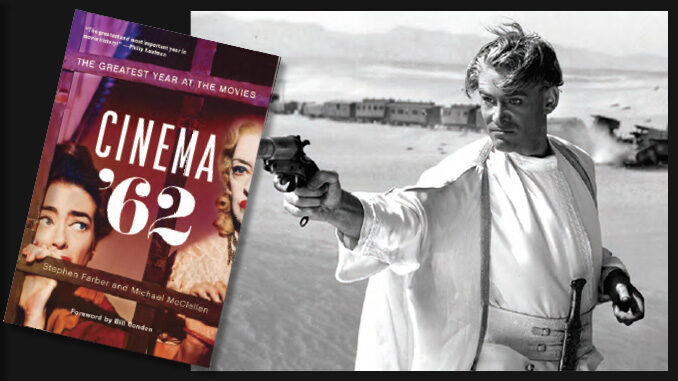

The subtitle of “Cinema ’62: The Greatest Year at the Movies” is an on-the-mark description of this light, entertaining work. More than a treatise on cinema, this is a book about movies: Films made for popular entertainment.

Debating the merits of different eras, productions, and filmmakers is a long tradition for everyone involved in filmmaking, on and off the set, including those in post-production. Farber and McCellan offer ample ammunition to anyone who champions films from the early 1960s. Editors will especially appreciate the attention given to the legendary editor Anne V. Coates. Her skills are celebrated in “Cinema ’62” for her artistic contributions to “Lawrence of Arabia.” Readers are even treated to a photograph of Coates at her Moviola. Coates recommended to the director David Lean that he watch the films of Truffaut, Godard, and others of the French New Wave to observe their innovative cutting. The authors write that after she put together a rough cut of the first scene sent to her, Lean “said one of the best things anyone has ever said to me: ‘you’ve cut that exactly like I would’.” They spent three months in London editing together, in the process creating what Farber and McCellan call, “One of the most famous cuts in film history, [the one] that jumped from Lawrence blowing out a match to the sun rising in the desert.”

“Cinema ’62” devotes an entire chapter to “Lawrence,” calling it the “Crowning Achievement” of the year. This may be debatable, but the picture was certainly one of the year’s biggest releases. It easily bested Cinerama’s “How the West Was Won.” “Lawrence,” with Robert Boyle’s emotionally nuanced script, Lean’s direction, breathtaking locations shot in Super Panavision 70 mm by Freddie Young, acting by an ensemble of non-stars, and Maurice Jarre’s score, were all backed by producer Sam Spiegel’s willingness to take on risk.

“Lawrence” was the top-grossing picture of 1962, earning $45,000,000, and Coates won the Oscar for her editing. Nine others earned Oscar wins or nominations for their contributions to “Lawrence,” including John Cox-Best Sound Mixing, Lean for Best Director, and Spiegel for Best Picture.

“Cinema ’62” is wisely organized thematically, not chronologically, and the 1962 designation is determined by release date. This approach is effective, and especially useful for covering non-English language titles, since some did not arrive on American screens until well after they premiered abroad. It also omits foreign language films that did not make it to the US that year. This choice is natural for writers who are primarily known as 1.) a film reviewer (Farber) and 2.) the film buyer for Landmark Cinemas. (McLellan). Much of the content is in fact drawn from previously published reviews, by Farber, Pauline Kael, and others. The result is a good survey of critical and box office reception and makes for easy reading, but also occasionally results in Hollywood Reporter and Movieline hyperbole.

The lists of awards and honors in the indices help back Farber’s and McClellan’s campaign for 1962, but the repeated inclusion of these facts within the body of the text is unnecessary and disrupts the narrative. Their reliance on Academy Awards as the great arbiter of quality can also be irksome. The Oscar carried more box office weight in 1962 than it does in 2020, just as it reflected popularity more accurately. As the authors themselves write, the Academy’s history reveals that it often overlooks greatness. “Cinema ’62” also lists some of the year’s films selected for inclusion into the Library of Congress National Film Registry, perhaps a better indicator of long-lasting value than any award. Like many, Farber and McClellan seem to believe the comforting idea that a listing in the Registry means that a film is preserved. This is ot the case. Although many titles (800 in all) are safely preserved, the Library’s designation indicates only that a film is a National Treasure, worthy of being preserved. Numerous titles still await funding for restoration and preservation. Readers will find historical insights, intriguing details, and seldom heard personal accounts that are absorbing and at times scintillating. The authors’ interview with David McCallum, who appeared with Montgomery Clift in John Huston’s “Freud”, reveals, “That sort of sadomasochistic relationship between John Huston and Monty Clift was quite extraordinary.” With comments like this, a dip into the main text should make readers keen to see or rescreen movies released in 1962. That in itself is an excellent reason to own this book, even given the small screens to which these movies are unfortunately now relegated.

The early ’60s was a more fertile time for movies than many think.

The psychological explorations of films like “Lawrence of Arabia” are mined from Farber’s previous book, “Hollywood on the Couch: A Candid Look at the Overheated Love Affair Between Psychiatrists and Moviemakers” (1993). One chapter of “Cinema ’62” discusses how Freudian theories were embraced by many in the film community, like Marilyn Monroe and director Sidney Lumet. Freudian psychology was undoubtedly au courant in the late ’50s and the early ’60s for artists and intellectuals who had time and money to explore their psyches. A perhaps surprising convert to psychotherapy was John Huston. His controversial WWII documentaries included “Let There be Light” (1946), the first important U.S. film to explore PTSD in veterans, and a precursor to Huston’s 1962 biopic “Freud.” Huston, quoted in an interview, said, “Very few of man’s great adventures, not even his travels beyond the earth’s horizons, can dwarf Freud’s journey into the uncharted depths of the human soul.” Farber and McCellan find Freudianism at work in many films. Mention of Satyajit Ray in this chapter compares his film “Devi” with the work of that most gloomy, psychologically absorbed director, Ingmar Bergman.

Other non-English language filmmakers fare better than Ray. The French New Wave, particularly Godard and Truffaut; Italians (Antonioni, Fellini and a great deal of Sophia Loren); and Kurosawa in Japan occupy much of the first chapter. The lone woman director in this chapter, Agnes Varda, “The Mother of the French New Wave,” outlasted all these, except Godard, making dozens of films from 1955 to 2019. Her 1962 feature, “Cleo From 5 to 7” is considered by many a classic of the French New Wave. True, there were very few women making films in the early ’60s, but rather than celebrate one of the few such as she, Farber and McClellan denigrate Varda by qualifying her, writing that “one French movie of 1962 was even directed by a woman.” Reflecting the culture of the time, 1962 saw no major US releases of films by Americans of color.

Other women filmmakers are mentioned, principally Shirley Clarke, but the emphasis is on press-worthy female stars such as Elizabeth Taylor, Rosalind Russell, Angela Lansbury, Doris Day, Jeanne Moreau, Sue Lyons, and Sophia Loren. The most attention is saved for Bette Davis and Joan Crawford in “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?.” These two, in a lurid color image—the terrified Crawford and the sinister Davis—pops up on the cover of “Cinema ’62.” The book explores the facts and the fictions that surround the making of the film, gives their due to these two inimitable stars, and considers “Baby Jane’s” lasting camp appeal. Farber and McClellan also employ “Baby Jane” as an emblem of the final gasps of old Hollywood. Only “Lawrence of Arabia” is given more space in the book.

Throughout, the authors clarify their message that the early ’60s was a more fertile time for the movies than many think. This era in Hollywood is sometimes written off as a time of waning talents, collapsing studios, the threat of television, and the box office triumphs of Elvis Presley. Historically, 1939 with “The Wizard of Oz,” “Gone With the Wind,” “Stagecoach,” “Ninotchka,” and others, is often lauded as filmmaking’s greatest year. Farber and McCellan aim to knock 1939 off that pedestal. In its reckoning of greatness, “Cinema ‘62” considers foreign language films, many of which have long been accepted classics. Such inclusion is impossible when assessing 1939, when the outbreak of World War II decimated film culture outside the US.

A case for either year can be made. Taking all factors into account, including what films are called cinema and which are movies, it remains up to the reader and the filmgoer to decide which of these is, ultimately, “The Greatest Year at the Movies.”

Cinema ’62: The Greatest Year at the Movies

By Stephen Farber and Michael McClellan Forward by Bill Condon

270 pages

Rutgers University Press

2020