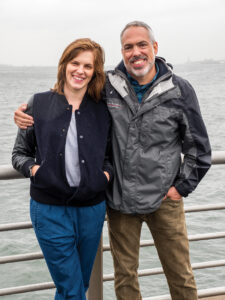

by Rob Feld • portraits by John Clifford

Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea made big news at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival with a $10 million sale to Amazon. The film tells the story of a blue-collar family in the North Shore of Massachusetts; Lee (Casey Affleck) is left legal guardian of his nephew (Lucas Hedges) when his older brother Joe (Kyle Chandler) suddenly passes away, forcing him to deal with a horrific past that destroyed his family.

Manchester, which opened in theatres November 18 through Amazon Studios, paints the rhythm and sonic universe particular both to that North Shore location and to its director. Collaborating with Lonergan to capture those qualities was picture editor Jennifer Lame and supervising sound editor, sound designer and re-recording mixer Jacob Ribicoff.

Lame moved to Los Angeles after graduating college and cut her teeth at a start-up that invented commercials out of found footage for companies with little budget. She found the feature film space challenging to penetrate in LA until a friend’s sister, Jennifer Lilly, called from Woody Allen’s cutting room in New York. Her apprentice editor had quit; if Lame could be there by Monday, Lilly would hire her and get her into the Editors Guild. She packed her bags and hopped on a plane.

“I got to work with Jen and Tom Swartwout, which made me love editing in New York,” she recalls. “It was such a contrast to LA. They were so supportive and willing to teach me stuff; there was clearly a community here.”

From there, Lame moved through New York’s scene, assisting editors like Naomi Geraghty, Arturo Sosa, Anthony Redman and Michael Taylor, until her work with Taylor on a low-budget indie garnered her first editor credit. She continued assisting, however, until she landed in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha (2012) cutting room, assisting Tim Streeto, ACE. Lame would stay late to work with the massive amount of footage after Streeto went home and, when he finally had to return to HBO’s Boardwalk Empire (2010-14), Baumbach gave her the chance to finish the film. It would be the end of her assisting days.

For his part, Ribicoff caught his bug for sound and film around the age of 11. He and a friend developed a hobby of mail-ordering 8mm silent comedies — Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd — and experimenting with different types of music played against them. In his college years, taking film classes and sitting through the credits to the bitter end, he saw people called sound editors and re-recording mixers. Thereafter, he would sit in the park and take notes on what he was hearing around him.

Ribicoff found a job with a pioneer in audio theory and practice, Tony Schwartz, and eventually found his way to location recording and post-production sound editing. “I realized that if you wanted to be in an environment where everybody was focused on the sound of the movie, it had to be post-production and not location mixing. I wanted a more creative experience with sound editing than that.”

Photo by Claire Folger/Amazon Studios

In the early 1990s, Ribicoff was struck by how evocative the atmospheric sound work was in Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990): the birds, gun battles, voices, battle cries. “You could look at a still image and feel as though you were there on that battlefield at dawn, with bodies strewn about,” he recalls. “You would hear just the right bird and it would place you right there.”

A break came when Ira Spiegel, one of Burns’ sound editors, eventually hired Ribicoff to be sound effects editor on The West (1996) and since then has been part of the documentarian’s core production group, currently wrapping up production on The Vietnam War (2017) as one of three sound designers.

In between Burns projects, Ribicoff worked in many positions on many projects, such as Foley editor on Gangs of New York (2002) and The Aviator (2004), and supervising sound editor on The Wrestler (2008). But the second pillar of his employment came when he landed a job as associate supervising sound editor on The Hours (2002), which began a longstanding relationship with producer Scott Rudin, for whom he has now supervised 10 films, including Lonergan’s troubled production of Margaret (2010). It was a long slog with Lonergan on and off the project at various points, but it formed the relationship that brought him eagerly to Manchester by the Sea.

CineMontage interviewed Lame and Ribicoff separately in July.

Jennifer Lame

CineMontage: You had a very good run in your early assisting career of great editors referring you to others, and got your first editor credit through Michael Taylor. Talk about your first time interviewing for an editor position.

Jennifer Lame: I had never interviewed for a proper editing job before, only as an assistant. It’s embarrassing, I didn’t think about how different the two interviews were; one being more based on technical skills and personality, and the other more about having a distinct creative take on the project. But I was cocky, read the script a few weeks prior and figured I would be fine. Well, obviously I wasn’t fine and the producer grilled me, asking me all these questions I hadn’t really thought about: At what pace would you cut this specific scene? What would you do here? What do you think about the tone? Which scenes would you cut; which wouldn’t you? I didn’t even bring a copy of the script to the interview, let alone a copy with notes. Suffice to say, I did not get the job.

Although it was one of the more embarrassing moments of my career, it ended up being great timing because a week later, I got a call. Michael Taylor said that Tim Streeto was looking for someone to assist him, but to also potentially do some editing on a Noah Baumbach movie, Frances Ha. This time I prepared really hard. I had all these ideas, made a list of music and movie references. I wasn’t allowed to see the script. But they told me what it was about, so I tried to do as much research and work as I could, based on that. I got the job as an assistant. By the time Tim had to leave, I knew the movie and footage better than anyone, and Noah had gotten used to me in our afternoon sessions. It was one of those combinations of working really hard and being in the right place at the right time, so it paid off.

CM: And it led to another three with Noah; you’re cutting Yeh Din Ka Kissa now.

JL: Noah and I get along very well. He and Greta Gerwig decided to do Mistress America [2015] right after Frances Ha, in a similar spirit and budget/business model. So I did that one and we hadn’t finished yet by the time While We’re Young [2014] was going into production. Tim was supposed to do it, but had some work conflicts. Noah was really generous and gave me the chance on the bigger one.

CM: How have you and Baumbach come to collaborate?

JL: I think Frances was such an editor’s movie; a character piece cut in such a specific way. Noah’s movies are cut pretty quickly; not necessarily long and sharply cut. It’s about making sure that it’s true to the characters and that things breathe when they need to. How does the way we are cutting the scene effect the character’s emotion? And as we cut, we go back and re-watch constantly to make sure we feel like we are doing justice to every single moment, which is really pleasurable. You don’t just put it together in a long form and tweak; you watch it and refine as you go.

CM: What is his approach to editing?

JL: Noah has always been very experimental with editing. He has a clear aesthetic, but he’s very open and curious about trying different things as long as they fit into the context of the movie, and drive the story forward in the best and most effective way. He very much enjoys and is protective of the editing process, as is Kenny [Lonergan].

CM: How did Manchester by the Sea come to you?

JL: I’m obsessed with Kenneth Lonergan. I think he’s incredible and I’m a huge fan of his work. I was desperate to get an interview. Somehow between my agency and others, I got sent two or three drafts of the script and read them all. I saw how they all changed but I didn’t get an interview. I was devastated. But then I got a call saying they hadn’t found anyone yet and would do a phoner; nobody thought I would get the job over the phone.

It was a little awkward. Kenny was obviously distracted, going into production really soon. But I realized I’d read these drafts of the script. We were talking about scenes they had eliminated and I said, “Oh, I remember these two scenes that you cut that I love, and I think it might have been a mistake.” It was a huge risk because he could’ve felt I was totally wrong, but if I didn’t do something big on the phone, I wasn’t going to get the job. But he said, “Oh my god, I was just talking to Casey [Affleck] and he felt the same way! I miss those scenes too and I’m definitely going to put them back now.” I think that got him thinking that this girl is really interested and engaged in this movie. So he decided to give me a chance, even though they were interviewing people with more experience.

CM: Then you didn’t actually meet him in person until he wrapped production. How did your process emerge?

JL: I’ll never forget when he first came in — it was really nerve-racking for both of us — we gave each other big hugs. I’d been doing a first cut, but he really wasn’t available to talk because the production schedule was so intense. I had just come off working with Noah, where we talk all the time and I go to set. It was really bizarre to go from that to never having met the person.

CM: The pacing of Manchester is completely different from a Baumbach movie.

JL: That was a challenge. Kenny has such unique rhythms in his writing. In the opening of the movie, you get to know Casey’s character through various jobs he does. It unravels in a slow but compelling way. I remember at some point I was asked, “Could this move a little faster, maybe cross-cut it?” I didn’t want it to be slow, so I tried different ways. One person I played it for said, “I don’t know which is Kenny’s version, but this one feels like a Kenneth Lonergan movie and the other one feels like some other movie. I want to see the Kenneth Lonergan version.” You can edit Kenny’s work faster and make the opening feel tighter and snappier, but it loses all of its specialness; it’s not a Kenneth Lonergan movie anymore. Even if people worried about it being too long, it was clear what it was supposed to be.

Then we took it to Sundance and there was a huge reaction to it, and we felt we did it right. But it was definitely a learning process; because Kenny’s rhythm is so different than Noah’s, I had to constantly respect and remind myself of the differences. A big part of editing is knowing what rhythm and pacing is right for the movie you are handed, but it was really interesting to go from one extreme style to another.

CM: There are a lot of threads to juggle in Manchester. There are flashbacks and moments that are more atmospheric. Was there a touchstone for you?

Photo by Claire Folger/Amazon Studios

JL: Early on in the process, Kenny was deciding whether to have a device for the flashbacks — whether to shoot them on a different stock or in a different aspect ratio. Eventually he decided not to do any of that, which I think was the right move. He was thinking maybe we’d come up with some device in editorial with sound or picture. We went through a bunch of ideas, but then threw them all out.

The way I decided to think about it was that they weren’t flashbacks; it was like we were cutting two movies at once: the present and then Lee’s life before the event in the middle of the film. If you look at the flashbacks, they’re not memories; it’s a narrative. If you cut the flashbacks together, they’re a mini-movie in and of themselves. So that’s how I thought of it, showing Lee before this thing shut him off to life and feeling. It’s an emotional journey, so I made sure to be both respectful of the emotion and not exploitative with it.

CM: What element most affected your selects?

JL: Performance. The actors in this movie are so incredible; they have various ways of breaking down. We had so much to work with. We could have had a scene with an actor completely breaking down, or one where he holds himself together more. It was deciding what was most respectful to the characters and performance — and what we felt was true to the subject of the movie. We weren’t trying to make people feel upset, but to understand. There was always that fine line to consider throughout the movie; if Lee just broke down in this scene, it would be a relief and you would just get it. But then maybe he can’t break down in this scene because it’s almost too painful for him to do so?

It was something Kenny spoke to Casey about a lot. This person is feeling so much pain that he has to shut himself off. If even a little pin pricks it, he will be destroyed. You don’t want people to think the character is cold, but that if he felt anything at all for a moment, he would explode. So there was the mystery of figuring out when the pin should finally prick him and he comes apart, and even how much he comes apart. Kenny had done so much work on that performance with Casey leading up to the shooting, and he brought that to the edit room.

CM: Is there something you’ve come to appreciate about Baumbach and Lonergan, which you hope to get again?

JL: Their obsession with getting it right. Neither one compromises, and by not compromising, they’re constantly explaining why they can’t compromise. Also, they both speak about their movies in ways that are so eloquent.

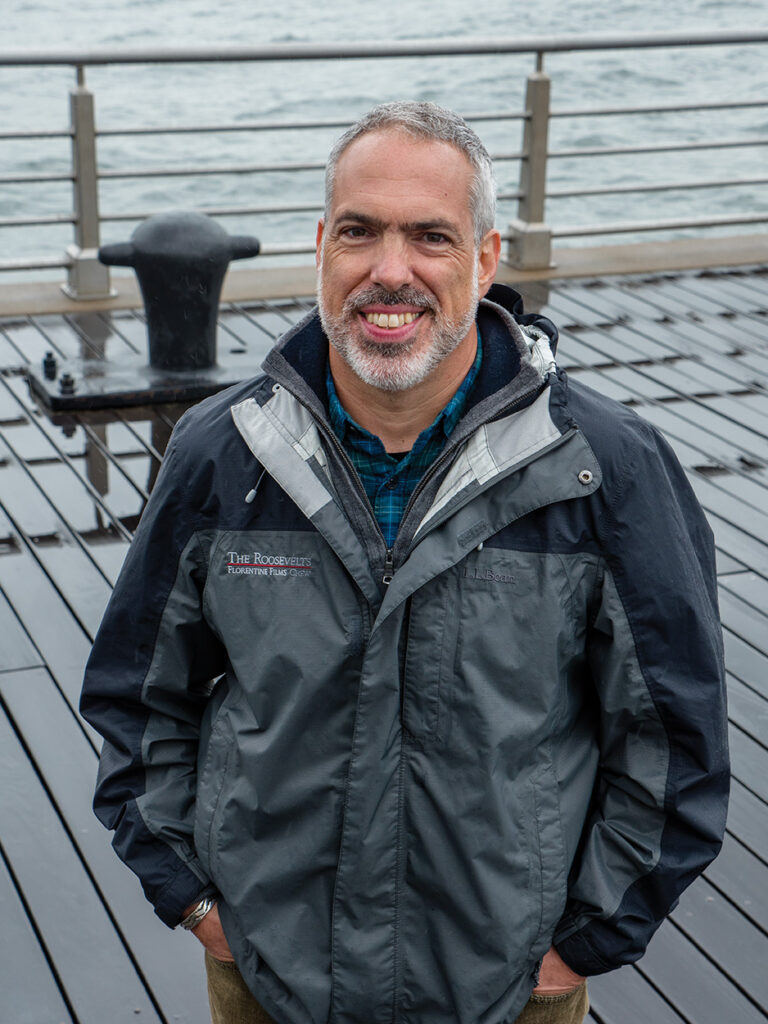

Jacob Ribicoff

CineMontage: Manchester was your second project with Lonergan on a very different sound-scape. How has your process with him developed?

Jacob Ribicoff: You always like working with a director who knows exactly what he wants, and that’s Kenny. I did sound supervising on the theatrical release version of Margaret. I did a spotting session with Kenny initially; he began talking about recording on the street, having voices of New York permeate the movie. I grew up in New York and was really excited about that. But by the time we finally mixed the theatrical movie, Kenny was not involved anymore due to legal reasons. We weren’t supposed to talk to each other. There was a guy from the bond company who was the authority figure on the stage. It was really weird, like playing in a band to an empty house. I tried to retain as much from the spotting session I had with Kenny to honor his aesthetics.

The movie sat on a shelf for four years until it was released theatrically, but for the DVD release, Kenny was allowed to do a director’s cut. I got to go back and redo the whole soundtrack with him. We retained chunks from the theatrical release, but really got to do it his way this time. In that mix he had very specific ideas of how he was hearing the city and how he wanted the viewer to hear it. You might normally use group ADR, but we wanted to use this huge collection of on-the-street voices he had recorded.

His idea was that if people are walking toward you and passing you on the street, you don’t fade up on their voices slowly until they reach you and then fade out as they walk away. Instead, you’re in a conversation, not paying attention, and suddenly the person’s right there — you hear three words and then they’re gone. That’s how we treated the voices in Margaret. We tried this approach in Manchester, but Kenny quickly found it to be distracting. So we shifted away because it’s not New York City; it’s a completely different environment. For Kenny, it was a different aesthetic to keep the voices not essential to the scene to a minimum.

CM: Would you call that realism?

JR: I would describe his approach as being a form of realism, except when music takes over. For example, in the fire flashback at the center of the movie. It becomes an operatic moment where music takes over and you have many sections of that MOS, no dialogue or any other sound. We played around with that fire scene, listening to the beginning and end where you see a fireman poking around in the rubble. We tried to have it so you just hear them poking around within the background music, then fell back from that reality to only music.

CM: So what was the need of Manchester from the sound design perspective?

JR: Manchester was about giving a real environment to the characters that never calls attention to itself, but really informs the dramatic situation the characters are in. Their words and the situation they’re in are first and foremost, but they are placed within an environment that makes sense. It had to be a place any viewer could associate with and not be pulled out of it in any kind of unorthodox way.

With that, Kenny’s view of which sounds belonged in that reality and which didn’t was very specific scene to scene. And if you were going to hear an engine throttling up to full speed or a dog barking, the timing had to be exact. It would be okay for a dog to bark between two particular lines of dialogue but not between the third and fourth. So a lot of our process was going through that meticulously, with Kenny having a total awareness of his script, characters and dialogue. It was an absolute sense of the music of the environment. However you could set that up, that’s what determined the aesthetic and what the movie would sound like.

CM: Do you start by defining a pallette from which to work or is it largely trial and error?

JR: I approach being a sound designer/supervising sound editor like an actor does a role, with the director as my guide. I want to get into the director’s head and fully understand how he sees the world and story he wants to tell. It doesn’t matter what I think personally, it matters what I can bring to the director. Certain directors might ask for my input and then I’m happy to get creative.

With this film, my input came from Kenny’s very specific ideas. I saw the movie first on my own before talking to him and had ideas for how to make the environment. The movie itself dictated a lot in the way it was shot. There aren’t a lot of wild camera moves or avant-garde elements onto which you would start to pin a more impressionistic type sound design. The movie is more straightforward.

When I finally started talking to Kenny, he said, “You’ve got to go up to the area where we shot — Gloucester, Beverly and Manchester by the Sea in Massachusetts — and record in the exact spots where the movie was shot. I spent a few days recording the boat sounds, the great fishing bar, Pratty’s, with fisherman in there. They were great about letting us record ambience with people telling stories and laughing at the bar, wondering out loud who we were with our microphones. At night, we recorded the air, the wind, dogs barking in front of the different locations, including the high school and hospital to get people’s accents from up in that part of the country. I think the movie shares its authenticity with Margaret. That was important to him.

CM: How do you juggle these different roles of sound designer, sound editor and re-recording mixer in this more indie film world?

Photo by Claire Folger/Amazon Studios

JR: It works very well, but it’s key to get help; I had a good dialogue and Foley editor, Roland Vajs, who pre-mixed the Foley. He did a great job with that, and even did some dialogue leveling, which was helpful by the time I got into mixing it.

In terms of how you approach it, you just make it work. It’s obviously a short schedule when it’s indie and low-budget, so you’re looking for people who can work quickly and effectively within a short period of time. It’s always a wrestling match between the budget and everybody’s resourcefulness and creativity. When my dialogue editor, Alexa Zimmerman, was no longer available while I was mixing, my ADR editor, Dan Edelstein, stepped up to help with dialogue and Foley.

CM: So you’re really a jack-of-all-trades in sound?

JR: I’ve done all the disciplines in sound editing between Foley, dialogue and music editing, but what I love most is sound design, which is really an alchemy of creating something from nothing to evoke something new. All of that comes into play when you’re a re-recording mixer/sound designer/supervisor. It got to a point where I was the only one on stage, so if Kenny said we need to do some music editing here, that was me. Or if he said the voices aren’t working and we need to find some others, that was me also.

Everything was happening in the one room we were mixing in, and Michelle Williams came in to do her ADR. For that I used a portable zoom recorder with a good microphone, the Neumann RSM-191; it’s a Mid-Side microphone they don’t make anymore, and you can use it as a shotgun mic. It has a great, clean, warm sound.

I think what Kenny really liked was knowing that everything was happening in that one room. You gather your sound, you have your crew do their thing, maybe some pre-mixing; the dialogue editor does some noise reduction; you have everyone pitching in, doing what was traditionally only a mixer’s domain.

CM: Is that usual?

JR: In New York, we have editors who also work to a certain degree as mixers on a routine basis. Definitely in an indie scenario, you’re looking for help wherever you can get it. So getting help from the other sound editors is part of the process.