by Peter Tonguette

In the countless comedies he has written, directed and starred in during his 50-year career, Woody Allen comes across as a chatterbox. His on-screen persona is forever opining, grousing or whining about one thing or another.

When editing a film, however, Allen adopts a decidedly different demeanor.

In 1976, Wendy Greene Bricmont, ACE, discovered for herself just what a calm, orderly atmosphere is maintained in the cutting rooms of Woody Allen. After serving as an assistant editor to Allen’s longtime editor Ralph Rosenblum, ACE, on several non-Allen films, including Bernice Bobs Her Hair (1976), Bricmont was invited to work on the duo’s latest and most challenging undertaking, Annie Hall. Although Bricmont was hired as an assistant editor, she moved up to editor during post-production and ultimately shared the editing credit on the film with Rosenblum; he received an opening credit, she an end credit.

Unlike the clear-cut farces that preceded it, such as Sleeper (1973) or Love and Death (1975), the film dissected the relationship of writer Alvy Singer (Allen) and singer Annie Hall (Diane Keaton) through a blend of scenes both comic and dramatic. The final brew was often funny but sometimes sad. In the interview book Woody Allen on Woody Allen, the director described his early efforts as consisting of a “series of jokes.” He added, “But it was not until later, when I did Annie Hall, that I became more ambitious and started to use the cinema a little bit.”

After its debut 40 years ago in March 1977, Annie Hall was honored with Academy Awards in four categories: Best Picture, Best Director for Allen, Best Actress for Keaton and Best Original Screenplay for Allen and co-writer Marshall Brickman. In 1998, the film’s stature was confirmed when the American Film Institute chose it as one of the 100 best films made in the United States.

Bricmont remembers the experience of editing Annie Hall as being relaxed — even serene. The setting in which the film was cut could best be described as “homey.” As recounted in Rosenblum’s 1979 memoir, When the Shooting Stops…the Cutting Begins, in 1975 the editor had installed editing equipment on the second floor of the Manhattan brownstone in which he resided. “It is a large room, lined with two Moviolas, a teak desk and five tables,” he wrote, “all topped with synchronizers, film winders and other little pieces of equipment.”

“He would just come downstairs and we’d start work,” Bricmont says. “It was such a collaborative and peaceful place. No one needed to fill it up with dialogue or talk through the whole thing. I remember Woody saying, ‘We’re smart. We should be able to figure this out.’ And you sat there with your head on your hands and thought about what to do.”

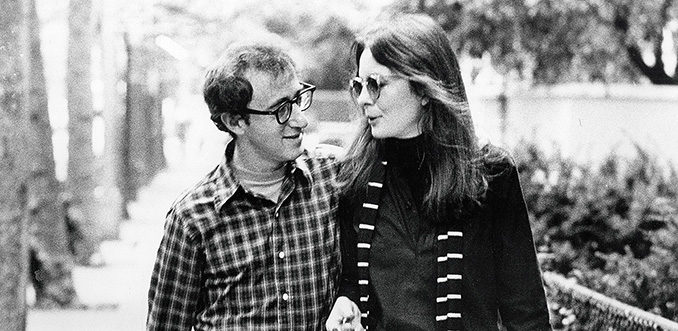

United Artists/Photofest

In between editing (and thinking), time was made each day to go out to lunch. “We never ate over our Moviola the way people often do,” Bricmont recalls. “We would walk over to Broadway. People would shout out to Woody, because he was so recognizable and very popular within New York: ‘Hey, Woody!’ He was very shy until he got to know you really well.” The hours were predictable, she says, with work routinely wrapping up by 5:00 or 5:30 in the afternoon. “Woody always had an appointment,” she remembers. “It was so civilized.”

In this environment, Anhedonia — the title to the screenplay by Allen and Brickman, an allusion to a condition in which a person is in a state of perpetual discontent — was rearranged and reworked into Annie Hall. Despite the amenable working conditions, the birth of the film was lengthy and labor-intensive.

According to Rosenblum, the first cut ran about two-and-a-half hours. Instead of accenting the relationship between (and eventual separation of) Alvy and Annie, this version branched out every which way. “The movie was like a visual monologue, a more sophisticated and more philosophical version of Take the Money and Run,” Rosenblum wrote. “Its stream-of-consciousness continuity, rambling commentary and bizarre gags completely obscured the skeletal plot.”

Of course, a number of digressions were retained in the film (such as scenes set during Alvy’s childhood in Coney Island or several fantasy set pieces), but they had overtaken the original cut. And supporting actors whose presence is only fleetingly felt in the film as it was released — including Carol Kane as Allison, Alvy’s first wife; Shelley Duvall as Pam, a Rolling Stone journalist who is one of Alvy’s post-Annie dates; and Colleen Dewhurst as Mom Hall, the matriarch of Annie’s clan — figured much more prominently in the first cut.

“It was just filled with so many wonderful, wonderful bits that were protracted and long but hilarious in and of themselves,” Bricmont recalls. “It had so many elements of surreal thinking and fantasy, but it was too much; it was overload. It wasn’t focused in a way that a movie needs to be.” Among the ultimately omitted segments was a dream sequence elaborating on Alvy’s perennial interest in Marcel Ophuls’ documentary on the French Resistance, The Sorrow and the Pity (1969). “Woody is a Resistance fighter and he’s being interviewed by the Nazis,” Bricmont says of the deleted scene. “He absolutely refuses to name names, but he pulls out this finger puppet. He says, ‘I cannot name names…however, he can.’ It was hysterical.” Another dream sequence reimagined Alvy and Pam as Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden as they engage in a risqué dialogue with God.

Yet, to function as a film rather than a smorgasbord of subplots and spoofs, Annie Hall needed focus. “I’m not sure that we came upon this right after we saw an early cut, but all [we] really cared about was the [Alvy and Annie] relationship,” Bricmont observes. “That’s what rose to the surface and that’s what we had to start to pay attention to. You didn’t care about Carol Kane that much. You didn’t care about some of the people who barely made it into the [final] cut.”

Thus began the process of winnowing Annie Hall to its eventual length of 93 minutes. After preparing the first cut on a Moviola, Rosenblum and Bricmont — along with assistant editor Susan E. Morse, ACE, who was soon to supplant Rosenblum (who died in 1995) as Allen’s regular editor — moved to a Steenbeck. “That was my opportunity to affect, under [Rosenblum’s] supervision, a lot of the changes,” says Bricmont, whose credit changed as a result. “That’s how I got that film editing credit.”

Because most of the soon-to-be-removed scenes played well, and many were funny or at least interesting, Bricmont says the prospect of removing them was painful. “It’s not so hard to lose things in post-production when they’re not working,” she says. “But they all worked. It’s just that we couldn’t have them all in there.” However, having identified the through line in the ebbs and flows of Alvy and Annie’s relationship, the editors had to be merciless about trimming superfluous scenes. As Rosenblum wrote, “The more we became involved in the plot of the relationship, the more we had to prune.”

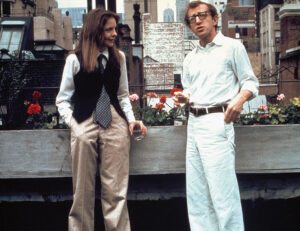

United Artists/Photofest

As Bricmont remembers it, however, Allen was sanguine about having his film reshaped. “It was amazing to see how he gradually and willingly let these things go — especially being the writer, director and actor,” she says. “Today, when you deal with directors, sometimes it takes weeks of massaging for them to let go of certain things.” As an example of Allen’s readiness to discard material, Bricmont remembers one scene filmed in Coney Island which featured 400 extras and took an entire day to prepare. “I heard that they did not roll any film until 4:00 in the afternoon,” she says. “They got this gorgeous, gorgeous shot, and it was one of the first things to go. He threw it out so easily.”

Rosenblum reported that Allen struggled to find a fitting finale for the film, which had changed so substantially in the cutting room. “Several conclusions were shot,” Rosenblum wrote, but in the end, the editor encouraged the director to write a voiceover to complement the opening monologue (in which Alvy invokes Groucho Marx to describe his problems with women). Allen heeded the advice and recorded the narration heard in the film today; after the two have split up, Alvy recounts going to lunch with Annie and then tells the immortal joke about the fellow whose brother thinks he’s a chicken but he won’t turn him in because “I need the eggs.” The voiceover is briefly paused for a succession of shots from the film — Alvy and Annie browsing in a bookstore, sitting on a park bench, etc. — over which Annie’s rendition of the song “Seems Like Old Times” plays.

“Woody hit that tone of being rueful and bittersweet and then Ralph created the callback of Annie singing and all the flashbacks,” Bricmont notes. “It’s been done so many times since then, and it was probably done a million times before that, but it took a long time to get there. And, for something that’s recognized as a romantic comedy, [spoiler alert] it’s not a very happy ending. They don’t end up together.”

In a sense, the conclusion parallels Bricmont’s own association with Allen. After working on Annie Hall, and receiving a 1978 BAFTA Award for Best Editing with Rosenblum, the New York-based editor moved to Los Angeles. Although she went on to edit successful and acclaimed films in Hollywood for such directors as Ivan Reitman and Howard Zieff, Bricmont did not work again with Allen. “I remember talking to him on the phone and he said, ‘You don’t want to move there. It’s terrible. It’s buggy,’” Bricmont recalls. “But I did move and I’m not unhappy that I did — although I probably would have had an opportunity to do more movies with him if I had stayed in New York.”

Even so, Bricmont has carried with her the lessons she learned while making — and remaking — Annie Hall, one of which is that a movie can begin as one idea, but often evolves into something wholly other. “You have in your mind that you’re making this horse,” she says. “Then you put it all together and look at it and it’s a different animal. On every movie I’ve ever worked on, it’s a case where you go, ‘Oh my gosh, this is a giraffe!’ And you proceed to figure out how to make it the best giraffe possible.”