by Debra Kaufman

When the cable channel Music Television (MTV) began airing music videos on August 1, 1981, with the prescient “Video Killed the Radio Star” by the Buggles, no one had seen anything like it. An entire network devoted to music, where your favorite bands sang the songs while they danced, cavorted in wild costumes, acted out stories and mugged in crazy environments. Editors also paid attention to the assemblage of shots in these previously unseen videos: lightning-fast edits, one after the other, that left the viewer breathless, maybe a little dazed––even confused–– but definitely excited.

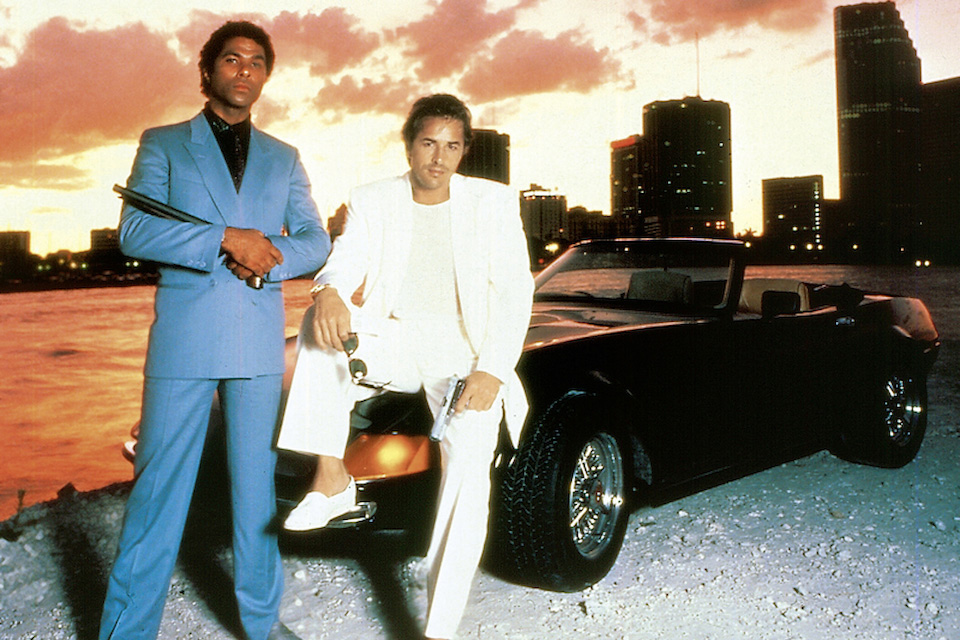

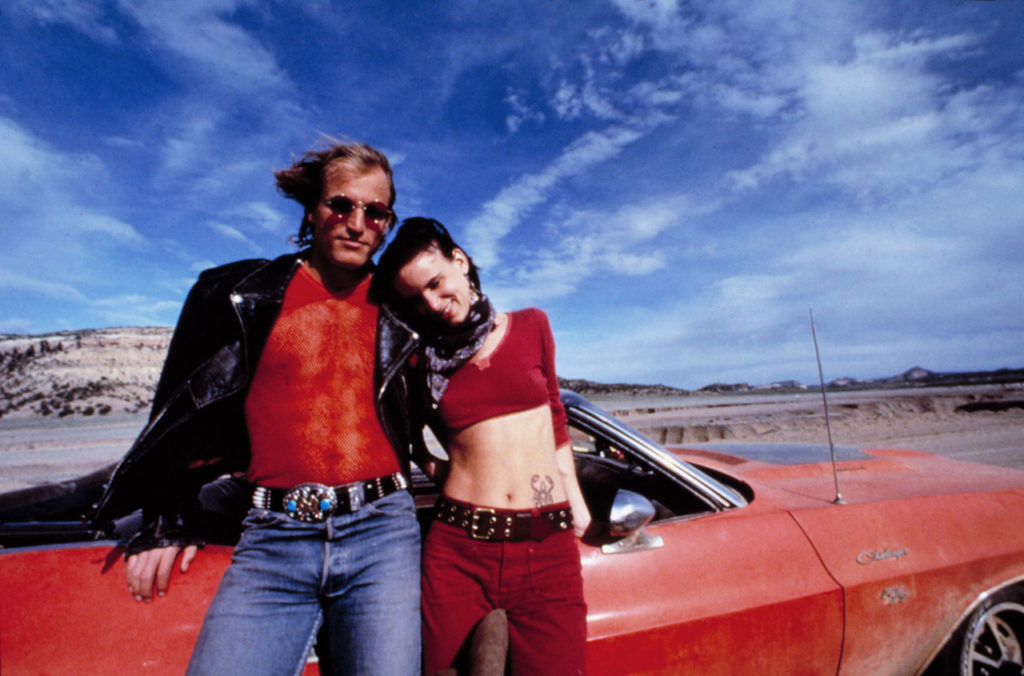

Moving pictures have never been the same since. MTV music videos—brash, experimental, so-rapid-that-you-simply-had-to-give-in-to-the-flow—quickly infiltrated every form of media, making their editorial style felt almost immediately in television shows like Miami Vice (1984-1989) and eventually movies like Flashdance (1983) and even Natural Born Killers (1994).

On the occasion of MTV’s 25th birthday, it is time to contemplate the results of this phenomenon. Has MTV reinvented or hobbled the art and craft of editing? Or, to bring the question to its essence: A quarter of a century later, what, if any, has been MTV-style editing’s impact on filmmakers and editors––and on the public that consumes the media they create?

CineMontage spoke to a half-dozen editors, all of them part of or touched by the MTV mystique, about their take on this media change.

Debunking the Myths

One misconception can be disproved right away. Not all editors cutting MTV-style were MTV fans. In fact, some of them had never even seen the cable channel. Robert A. Daniels, ACE, now retired, held the longest tenure as editor on Miami Vice. Although the producers reputedly sold the show to the network by describing it as “MTV cops,” Daniels admits he didn’t have cable when he was cutting the show and had seen only one or two MTV music videos.

Despite its precursors, the birth of MTV was still a monumental event, because it validated an entire generation’s obsession with music and became a living repository of its dynamic culture.

“When I saw the Miami Vice pilot, I said, ‘I’ve got to do this,’” Daniels recalls. “It was exciting adventure, and the music made transitions from scene to scene, something you wouldn’t ordinarily get.” Although Daniels wasn’t MTV-savvy, he was no stranger to editing to music. He cites his work as an assistant editor for director Bob Fosse on Sweet Charity (1969). “Bob did a number with Sammy Davis, Jr. and had him jumping from location to location in the middle of a song,” Daniels recalls.

Another myth to debunk: MTV was not the first instance of music married to film, as Busby Berkeley musicals of the 1930s and ‘40s can attest. Even in terms of a self-contained environment of short-form music and film, MTV has its precursors. “Sound-ies” were three-minute, black-and-white films with an optical soundtrack, and were played on “film jukeboxes,” self-contained, coin-operated 16mm rear-projection machines that were in bars, nightclubs, restaurants and other public places in the 1940s. They were also sometimes screened in theatres as “shorts” before the feature attractions. Sound-ies were made for every kind of music imaginable, from swing to gospel, jazz to hillbilly. Though they only existed from 1941 through 1947, in that brief time, more than 1,800 were produced and distributed.

These connections didn’t escape the earliest music video creators. Still photographer Gjon Mili had directed a memorable soundie, “Jammin’ the Blues,” a 1944 jam session of many early jazz greats, including Lester Young and Harry “Sweets” Edison, that has remained fresh and interesting. This soundie is said to have influenced pioneering music video directors/musicians Kevin Godley and Lol Crème when they made the acclaimed 1987 music video for the Police’s “Every Breath You Take.”

Editor Brian Berdan, ACE, also points to the impact of the 1960s combinations of music with imagery and lightshows as a precursor to MTV videos. “The music was free-form and allowed the form of the visuals to be free,” he says. “‘Music videos’ from the 1960s were pretty raw, with psychedelic lights and video mixing, but they were making some films.”

The 1969 film Easy Rider inspired editor Doug Ibold, ACE, long before MTV aired its first music video. “I think that what editor Donn Cambern did on that film was absolutely a-mazing––to bring music in to be part of the odyssey,” says Ibold, who was an editor on Miami Vice and, much earlier than that, was involved in documenting the 1972 Rolling Stones tour for the BBC Top of the Pops music show, as well as John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s “One to One” concert the same year at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. He also worked on the “pre-video” short films of all the songs on Lennon’s acclaimed Imagine album in 1971––a full decade before MTV was born.

Speaking of Lennon, editors also point to the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night (1964) as a strong antecedent to MTV’s meld of popular music, imagery and storytelling. “What that film did was take the ‘new cinema’ concept of film that had come out of commercial techniques––like speed-ups and jump-cuts––and used it in a narrative framework that follows the Beatles’ characters,” says editor Mark Goldblatt, ACE, who edited several fast-paced films for director Michael Bay, including Armageddon (1998) and Pearl Harbor (2001). Goldblatt also points to director John Boorman’s Having a Wild Weekend (aka Catch Us If You Can,1965), starring the Dave Clark Five as a similar forerunner of MTV. “A lot of the scenes are self-contained and could be considered early music videos.”

Back to the Beginning

Despite its precursors, the birth of MTV was still a monumental event, because it validated an entire generation’s obsession with music and became a living repository of its dynamic culture. “It was a great culmination,” says Goldblatt. “MTV had to be, because our generation was very involved in music, and when MTV appeared, we thought of it as a godsend.” Goldblatt feels that the time was right for a venue in which one could see reflections of that music in imagistic ways. “It was just fast cutting,” he says. “All kinds of possibilities existed to create great visual representations of the music.”

The first, most profound impact of MTV was its existence as an outlet. “There were so many videos made,” recalls Michael Heldman, who cut music videos in the 1980s at Propaganda Films. “The bands would sign album contracts for two videos per album. It was the marketing tool.”

When contemplating the impact of MTV on popular culture, most people instantly think of fast cutting, montages and other oft-used music video conventions that are now routinely found in TV shows, feature films and even commercials.

Experimentation

The upshot of MTV was that it opened a floodgate of content. Hundreds of music videos had to be made, with tight turnarounds (sometimes two weeks) and small budgets. “You could experiment a lot more than within the time frame and budget of features,” says Heldman. “A lot of the early music video directors didn’t have a strong film background; they came from graphics and design and were used to what they could do in that world. So they had a ‘whatever I can do’ attitude towards music videos. MTV made all these different styles acceptable within a pop context. Music videos consolidated a lot of styles that had long existed, but came together as a library of styles that were acceptable.”

Several editors note that music videos brought back some of the experimentation and flexibility of the early days of silent filmmaking. “Some of the techniques used in music videos are old,” notes Goldblatt. “Once sound and the blimp camera came in, the cameras didn’t move as much. The interesting thing is that the camera and editing styles were more kinetic in silent pictures.

“MTV took a lot of chances,” he continues. “There was a wide variety of music, and it was all visual, so it gave a lot of directors a chance to try things. When MTV appeared, the impact was incalculable.”

An Incubator for Talent

MTV also had a profound impact on the development of talented filmmakers, including editors, from its earliest days. Jim Haygood, ACE, who won MTV Video Awards for directing Paula Abdul’s “Straight Up” in 1989 and Madonna’s “Vogue” the following year, emphasizes that, especially in the early MTV days, music videos were a “second-class citizen” of the filmmaking world. But that was a good thing. “Since there wasn’t the level of scrutiny, it gave a lot of us a chance to work and not go through the traditional film editor’s pathway from assistant to editor,” he says. “You got to just do it. It was a chance for cinematographers, directors and editors to work with real money and develop careers in something that was new. A lot of us were able to get in there and jump in before MTV was on the radar.”

Haygood, as an online video editor at One Pass in San Francisco, had cut some music videos for director David Fincher in the mid-1980s. He moved to Los Angeles and joined Propaganda Films, a powerhouse for music videos that proved to be an incubator for directors (Fincher, Bay, Domnick Sena, Nigel Dick and many others) as well as editors (Heldman, Robert Duffy, Tom Muldoon, Haines Hall, Angus Wall, John Murray) who all cut their editorial teeth there. And they all took their MTV experiences and training to the next level––feature films, television and commercials.

Music Video and Technology

MTV also played an interesting creative role in the development of technology, say some editors. “Most people were editing on three-quarter-inch machines,” says Haygood, who is currently editing The Astronaut Farmer for Michael Polish. “They were linear systems and you couldn’t manipulate time the way you can now. But the weakness of the technology didn’t matter, because you were working within the fixed length of a song.”

Instead, linear editing sometimes led to serendipitous accidents. “If you’re recording over what you had before and hit ‘Stop,’ it’ll pop out to whatever was there before,” he says. “Sometimes, two shots end up together and it gives you an idea. A lot of that is gone with the Avid, although it is a better tool.”

Telecine also got a boost from MTV, according to Heldman. “Telecine was just developing from an engineer’s tool to an artist’s tool,” he says. “Music video directors, who often came out of graphics and design, pushed those tools. That led to the development of telecine to create ‘looks,’ which in turn pushed more technology.”

The Impact on TV and Film

When contemplating the impact of MTV on popular culture, most people instantly think of fast cutting, montages and other oft-used music video conventions that are now routinely found in TV shows, feature films and even commercials.

MTV, with its multiplicity of styles and endless experimentation, has had an impact on editing, but in a manner much more complex than just quick cuts. First, the channel played a role in audiences’ acceptance of then-new editorial styles. Some critics charge that MTV is responsible for all the bad, fast-paced editing, but Haygood has another point of view.

“Sometimes, things do get cut too quickly, partly because that’s what the audience has gotten accustomed to,” he says. “Sometimes people say they hate dissolves, but dissolves have their place. So the fast cuts technique has its place too, but it’s about using good judgment. It depends on the content of the film. Fight Club [1999], for example, was more suited to that modern style, because there’s an audience that the movie is for. Some people resist change and don’t like it. But it’s all about the material.”

Although MTV’s impact may have softened over the years, as its revolutionary ideas have become more accepted, it still plays a role in popular culture and, hence, in editing.

Daniels feels that MTV is no longer impacting editing as much as it once did. “You can only go so fast for so long––and tastes change,” he says, noting for example that the Law & Order shows use a simple cue, not music, to transition between scenes. “In television, MTV-style editing is not being used the way it was,” Daniels concludes. “But it’s still a tool people can and do use.”

Berdan co-edited (with Hank Corwin, ACE) Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, a film often cited as an MTV-influenced. Never a big MTV viewer, Berdan (who is currently editing Crank, directed by Mark Neveldine and Brian Taylor) says editing has been inspired by the culture overall. “We are inundated by so many images every day that we learn to take them in quickly,” he says. “MTV is part of that culture; it’s the same thing.”

“Zeitgeist” is the term that Goldblatt uses to describe the impact of MTV, and culture in general, on editing. “MTV influenced the kinds of movies that people wanted to see, the kinds of movies that were being made and the technique,” he says. “With MTV, you were exposed to all the possibilities of music all the time. The collective consciousness was going in a certain direction, and MTV became a place where it distilled. Sometimes it’s not so obvious that a movie might be impacted by the music. It’s a cultural, zeitgeist thing.”

MTV did create some very specific editorial techniques, some of which have faded away while others remain. “Lots of films in the 1980s had a montage scene in the middle of time moving forward,” says Heldman. “It isn’t new––think of calendar pages falling in the classic films––but it made its way into dozens of films, and it came from music videos.”

MTV has had “a huge impact on how people treat the storytelling process,” according to Ibold. “If anyone doubts that, just look at how many episodic TV shows now end the episode with a dramatic song rather than the score. And observe how a very important part of a feature film release is to have a soundtrack to go with it. In most cases, it’ll include songs from the movie that are included, not the score,” he says. “Obviously, with regard to songs and music in TV and film, MTV has had an enormous impact.”

Music videos brought back some of the experimentation and flexibility of the early days of silent filmmaking.

Goldblatt points to The Terminator, which, in 1984, was his breakthrough movie as an editor. “Is The Terminator influenced by music videos?” he asks. “I couldn’t swear that’s true, but there are a lot of rhythms in that movie. We were all children of rock ‘n’ roll and for a director who has a musical sense, maybe a scene is kind of like a guitar riff.”

Although MTV’s impact may have softened over the years, as its revolutionary ideas have become more accepted, it still plays a role in popular culture and, hence, in editing. “That revolution pushed us into an evolution that’s still going on,” claims Goldblatt. “When MTV appeared, it seeped into mass consciousness and now is part of everyday life––like Starbucks.

“But you still go to MTV to hear the new music, and it’s always revolutionary because it’s tuned to the times,” concludes Goldblatt. “MTV itself has evolved to become more cultural, more cinematic. I’m still a fan.”