by Edward Landler

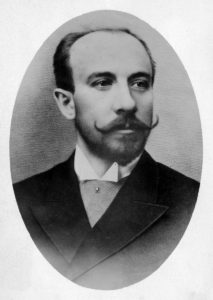

“I was the one who successively came up with all the so-called ‘mysterious’ cinematographic techniques. The cinematographers of artificially arranged scenes have all more or less followed the path I laid down.” — Georges Méliès, “Les Vues Cinématographiques: Causerie (Cinematographic Views: An Informal Lecture),” L’Annuaire Général et International de la Photographie (The General and International Annual of Photography), 1907

By the time film pioneer Georges Méliès made this only slightly exaggerated claim, the making and exhibition of narrative film was establishing itself as a business separate from the variety stage and lecture circuit. As more people visited storefront theatres to see moving picture stories, they watched the art and craft of editing evolving on screens right before their eyes.

Within the next 10 years, the emergence of feature-length films gave birth to an entertainment industry boom and, soon after, lavish movie palaces. Before 1900, however, editing — the selection, timing and arrangement of shots to draw attention from image to image within a scene, and to achieve continuity from scene to scene — was just barely imagined.

Throughout the 1890s, virtually all films exhibited were uncut, single-camera setup shots that were about a minute in length. Having made over 200 such pieces between 1896 and 1899, Méliès sought to expand these limited tableaux vivants (living pictures) into longer films and richer stories. He was among the first to imagine and contrive what would become editing and post-production in movie storytelling.

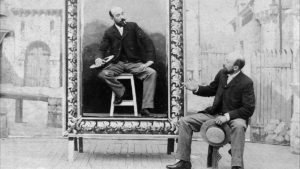

During the spring of 1899, 120 years ago, Méliès filmed and exhibited Le Portrait Mystérieux (The Mysterious Portrait), advertised in his Complete Catalogue of Genuine and Original “Star” Films (1905) as “une grande nouveauté photographique” (a grand photographic novelty). It was the first film to demonstrate what a “cut” can do within a scene. It portrays a primitive cut — substituting one image with another — within a picture frame placed in the movie’s single, uncut, continuous master shot.

In this short movie, the bald, bearded Méliès himself — gesturing like the magician he was — walks onto a theatrical stage, passes behind and steps through a large empty picture frame center stage. He places a landscape painting in the frame and a stool on the frame’s lower edge in the landscape.

With a wave of his hand, the landscape and stool in the frame “cut” to black and a second Méliès sitting on the stool in the painting dissolves into focus in the frame. The two men acknowledge and speak to one another; the Méliès outside the picture frame waves again, and the landscape with the Méliès inside the painting un-focuses into black. A “cut” brings the image of the hilly landscape with the empty stool back into the picture frame — and the movie is over.

Star Film Company

To achieve the effect of a cut, the filmmaker used mattes and stop motion. By the 1890s, mattes were common practice of still photographers to create double exposure photos. For The Mysterious Portrait, a matte masked the interior of the picture frame while the whole scene outside the frame was photographed. Then, after rewinding this master shot to the precise film frame, another matte masked the entire shot outside the picture frame and the interior of the frame was shot. To simulate these “cuts” within the picture frame, Méliès utilized the stop-motion technique he had developed to make people and objects appear, disappear or change form in his earlier fantastical movies.

Méliès had discovered moving pictures — a series of photographs projected rapidly enough to create the illusion of movement on the screen — on December 28, 1895, at the Grand Café’s Salon Indien in Paris. He was invited there by Auguste and Louis Lumière for the first public screening of 10 actualités (documentary views) the brothers had filmed — and projected — with their patented cinématographe (a combination movie camera and projector).

In 1890, Thomas Alva Edison and W.K.L. Dickson first created movies on their Kinetograph. But these films could only be viewed by one person at a time on Edison and Dickson’s bulky, peepshow-like Kinetoscope. However, the Lumières’ cinématographe could also project its films for viewing on a screen by an audience. More than anyone in the late 1890s, Méliès persistently tried to invent ways to use these machines to tell stories.

Since 1888, he had been the owner and director of the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, founded in 1845 by Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, the first great modern magician. Up through his introduction to film, Méliès had invented more than 30 elaborate “theatrical illusions” or magic tricks and, in 1895, was elected president of the Chambre Syndicale des Artistes Illusionnistes (Trade Association of Illusion Artists).

The Lumières refused to sell him a cinématographe, but others were fabricating similar moving picture machines. In February 1896, Méliès bought a Kinetoscope copy manufactured by Robert W. Paul, an English instrument maker and early filmmaker. The magician studied its mechanism, designed his own camera/projector and had it constructed by his theatre’s machinist, Lucien Korsten. While in London, Méliès also bought a crate of Eastman Kodak film; back in Paris, he perforated it with holes to fit the sprockets of his own machine.

Théâtre Robert-Houdin presented its first film program on April 4, 1896, and went on to screen films as part of its daily programming of magic shows and variety acts. In 1897, Méliès finished building his Star Film studio in Montreuil, a suburb of Paris. The main building’s walls and ceilings were all glass, and the dimensions of the main stage were the same as those of his theatre. Méliès rarely moved his weighty camera and photographed all his movies as performed on a theatrical stage.

The minute-long films he made included burlesques, comic anecdotes, fairy stories and fantasies, staged depictions of actual events, satires, scenes from literature and even the first screen advertisements. In his “Les Vues Cinématographiques” lecture, Méliès complained that these short movies were “unconnected fragments” and that he was “like the compère [host] of a revue, there to link the acts that have nothing to do with each other.”

In 1899, shortly after achieving the “cuts” within the single-scene The Mysterious Portrait, the filmmaker broke away from exhibiting only fragmented images and anecdotes. Trying to create cohesive continuities from multiple separate scenes, he experimented with longer and more involving stories. Méliès’ first significant attempt was a series of 11 staged tableaux filmed as actualités reconstituées (reconstituted documentaries), comprising a primitive docudrama of an era-defining military scandal then polarizing the French Third Republic.

In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer, was framed for treason and sentenced to life on Devil’s Island, the infamous penal colony off the coast of French Guiana. Accusations of official corruption, cover-ups and anti-Semitism provoked public controversy and, in 1899, Dreyfus was returned to France to be retried.

While the new court martial proceeded through August of that year, Méliès began shooting the segments of L’affaire Dreyfus (The Dreyfus Affair), perhaps the first politically engaged motion picture. In film historian Georges Sadoul’s 1961 biography Georges Méliès, the filmmaker’s widow, actress Jehanne d’Alcy states, “Méliès was pro-Dreyfus… He was a free-thinker.”

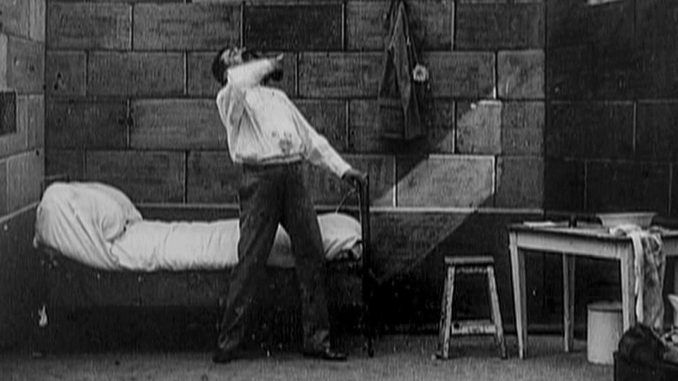

Depicting the major events of the affair — from Dreyfus’ setup and arrest, through imprisonment on Devil’s Island and his return to France — the uncut, single-shot scenes were all filmed at the Star Film studio and completed in September. While still filming the final tableaux, Méliès exhibited the earlier one-minute segments, and also rented and sold prints individually to other exhibitors.

When the last segment was shot, showing Dreyfus’ conviction upheld by a majority of the court, Méliès trimmed the heads and tails of all 11 scenes with scissors. Then, scraping off the emulsion at the ends, he glued the scenes all together in order to make one continuous film (running close to 13 minutes), which he released late in September 1899. Meanwhile, on September 21, public reaction to the trial had impelled the government to pardon and release Dreyfus. (In 1906, he was finally fully exonerated and allowed to return to military service.) Opening in New York City on November 4, 1899, The Dreyfus Affair circulated internationally for years.

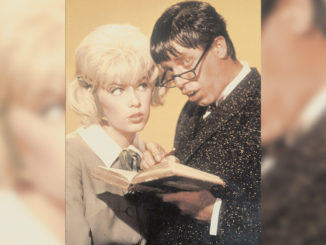

After completing that groundbreaking project, Méliès immediately took another step toward editing the arrangement of images to tell complex stories. Inspired by a pantomime staged by the Troupe Raymond at his theatre in 1897, the filmmaker shot Cendrillon (Cinderella), described in his studio’s film catalogue as “une grande féerie extraordinaire” (an extraordinary grand fantasy).

Running about six minutes, this version of the classic fairy tale was shot on one reel in continuity on four different sets prepared consecutively on the main Montreuil studio stage. Méliès created in-camera lap dissolves as transitions between the four sets: Cinderella’s kitchen, the Royal Palace ballroom, Cinderella’s room and the church exterior where she and the prince are wed. Within the separate tableaux, the filmmaker also used a few shorter dissolves to suggest passage of time, as well as stop motion for the story’s magical transformations.

Star Film Company

Premiering at Théâtre Robert-Houdin in October 1899, Cinderella was an immediate success, opening on Broadway in New York two months later on Christmas Day. The acclaim the film received encouraged Méliès to make longer, more elaborate films, using “all that I have learned by the seat of my pants during long years of constant labor,” as he stated in his 1907 lecture.

Among his most popular later films were the 10-minute historic spectacle Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc), 1900, as well as the science fiction fantasies Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon), 1902, 13 minutes, and Voyage à Travers l’Impossible (An Impossible Voyage), 1904, 24 minutes. Except for cutting and gluing together the scenes of The Dreyfus Affair, all of Méliès’ editing until 1903 was done in-camera before he developed his negative.

Post Méliès

In 1900, English film pioneer George Albert Smith made two short films that required actual cutting. That September, his one-minute As Seen Through the Telescope inserts a close shot of a woman’s ankle to show what an old man is viewing in the master shot. And that November, in Grandma’s Reading Glass, a medium-long shot of a woman and her grandson is intercut with POV close-ups of objects the boy looks at through his grandmother’s magnifying glass. In the same month, another British filmmaker, James Williamson, intercut reverse angle shots in Attack on a Chinese Mission, portraying an incident from the Boxer Rebellion.

George Albert Smith Films

Working for the Edison Company in the US, Edwin S. Porter firmly laid the editing foundation of movie storytelling in 1903 with Life of the American Fireman and The Great Train Robbery. With sequences constructed from images shot from a greater variety of camera distances and angles, and parallel action and cross-cutting used more extensively, these story films were instantly popular and were exhibited more widely and longer than any previous productions.

In 1914, Porter told the early trade journal The Moving Picture World that, motivated by this success, “We devoted all our resources to the production of stories [italics Porter’s], instead of disconnected and unrelated scenes.” With increasing public demand for movie stories, most production companies did the same. Between 1905 and 1908, over 10,000 nickelodeons and other theatres had been established in the US exclusively for film exhibition.

Prior to this, however, sometime between 1900 and 1905, the splicer — the first mechanical apparatus invented specifically to facilitate the cutting and joining of segments of film — had appeared. Actually, exhibitors were the first to construct hand-tooled splicers to join together the separate, single-shot views, images and short movies they rented or bought to screen them for audiences as one continuous program.

From 1905 on, filmmakers began seeing themselves as storytellers and took decisive control of the arrangement of shots in their work. By 1910, the standardized manufacture of splicers expressly for film editing and post-production had been introduced to the growing motion picture industry. In all likelihood, Méliès himself used a splicer before his film career ended in 1913, with over 500 movies to his credit.