by Edward Landler

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” – William Faulkner

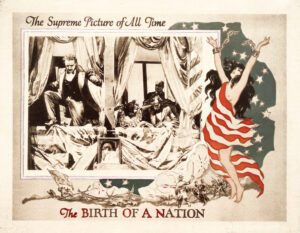

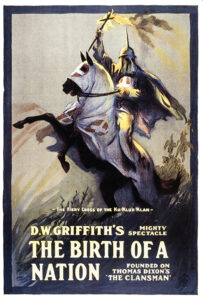

One century ago, on February 8, 1915, David Wark Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation premiered under its original title, The Clansman, at Clune’s Auditorium in Los Angeles. The irony of this premiere’s 100th anniversary falling in Black History Month is now magnified by the ongoing brutality exacted upon African-American lives by police. Both Griffith’s film and current events underscore the persistent practice of inequality that continues as part of our legacy as a nation.

There is no way around Birth’s influence on the history of film as an art form or as an industry. Its success ignited the phenomenal growth of the studio system and the proliferation of movie theatres instead of nickelodeons. Hollywood and audiences swiftly grew past the filmmaker’s 19th-century dramatic sensibilities but, as Charlie Chaplin noted at Griffith’s death in 1948, “The whole industry owes its existence to him.”

There is also no way around the influence of the film’s view of the Civil War and Reconstruction on how Americans as a people regard one another — and how movies reflect and influence our own attitudes. Its carefully researched historical trappings give credence to a deeply biased distortion of history. A volatile mix of real emotion and tawdry sentiment, the movie undercuts the critical assumption that technical innovation in and of itself gives it the authority of great or meaningful art.

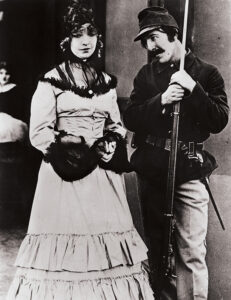

Two images sharply contrast the perception and blindness that pervade Griffith’s understanding of humanity and history. Halfway through the film, after a romanticized yet realistic depiction of war, the son of a plantation owner returns to his ravaged homeland. In his ragged uniform, he pauses at the entrance of his house as the arm of his unseen mother emerges to draw him inside the door. It is a touching evocation of loss, human ties and enduring hope.

Near the film’s end, in close-up, the huge fist of a black man is held in threat against the terrified face of the white heroine, played by Lillian Gish. In an over-the-top melodramatic portrayal of Reconstruction, this daughter of a “misguided” abolitionist is being forced into marriage with a “mulatto” politician who proclaims his intention to “build a Black Empire and you as a Queen shall sit by my side.”

For what it’s worth, The Birth of a Nation is the first real movie — the first feature-length motion picture to register that sustained enjoyment of being caught up completely in a film’s world. Its opening marks the real birth of the movies as a popular storytelling medium. It was the first to fully involve an audience emotionally in a richly detailed story, conveying a whole theme and embodying a whole world-view. It also demonstrated the power of craft to celebrate the false.

More than anyone, Griffith transformed static, verbosely intertitled, stage-like tableaux into dynamic narratives engaging audiences through imagery, varied camera placement, camera movement and editing. Though he did not introduce specific techniques like the close-up, POV or cross cutting, he was the first to integrate the increasing variety of cinematic elements into a fluid pictorial narrative that prompted emotional identification with the story.

Starting in 1908, in about 450 short films made for the Biograph Company, Griffith developed a pictorial language of observation and visual implication to convey character, motivation and plot. Spurred by the epic scope and action of early Italian features to make longer movies, he left Biograph in 1913 to sign with Harry Aitken’s Reliance-Majestic Studios, the producing wing of the Mutual Film Corporation.

Griffith brought with him from Biograph his favorite actors, including Gish, Henry Walthall and Mae Marsh, as well as cameraman “Billy” Bitzer and editor James Smith. Rose Richtel became Smith’s editing partner at Reliance-Majestic and his partner-in-life when they married during the production of Griffith’s Intolerance in 1916. They edited many of Griffith’s features together.

Moving his troupe to Los Angeles, the director quickly produced four short Mutual features. Then Aitken gave him a $40,000 budget for a 10-reel Civil War feature for the 50th anniversary of the conflict’s end. The sum was four times the usual amount spent on features of the time.

The Kentucky-born Griffith based his story of the war’s losing side on The Clansman, a novel and a play by Southern clergyman Thomas Dixon, and another Dixon novel, The Leopard’s Spots. He enlivened the war half of the film with the tales he heard from his Confederate colonel father, “Roaring Jake” Griffith. The heart of the post-war story, though, was the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, noted in an intertitle as “the organization that saved the South from the anarchy of black rule.”

The film does not acknowledge the brutality of slavery or the humanity of African Americans beyond loyalty shown to their former masters. In a 1943 interview, camera operator Karl Brown recalled leading lady Gish asking the filmmaker if his depiction of race might cause problems when the picture was released. Welcoming controversy, like many a producer since, Griffith said, “Then you won’t be able to keep audiences away with clubs.”

After six weeks’ rehearsal, production began, with high-minded symbolism intended, on July 4, 1914. It was shot in 12 weeks spread over five months in the Kinemacolor Studio and locations in the San Fernando Valley, Whittier, Ojai, Big Bear and the cotton fields of Calexico. There was no shooting script. Griffith directed the entire film from a visualization of the story worked out in his mind, fine-tuning it as he went along from set-up to set-up and, later, in editing.

Occasionally, he took time off from shooting to raise more money. The budget finally rose to $110,000, making it the most expensive film yet produced in America. Among its investors were a Hollywood lunchroom proprietor, a Ford dealer from Pasadena, an enterprising widow and William Clune, who owned the theatre in which the film would open.

By the time the film premiered as The Clansman, it was 12 reels (13,058 feet) and ran over three hours — the longest feature to date. Fearing financial disaster, Mutual refused to release it, leaving Griffith and Aitken to form the Epoch Producing Corporation to handle distribution.

The movie’s impact was immediate. In Los Angeles alone, it ran exclusively at Clune’s for seven months.

The most sophisticated features of the time rarely exceeded 100 separate shots, but Griffith and editors Smith and Richtel cut together over 1,500 shots to carry audiences through the story. The silent film’s editing rhythms were heightened by an orchestral accompaniment arranged by composer Joseph Carl Breil. With Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” as a background, no wonder viewers cheered the Ku Klux Klan’s ride to the rescue of whites beset by rampaging black hordes.

Just 10 days after the premiere, the film became the first motion picture screened at the White House — at the request of President Woodrow Wilson’s friend from graduate school, Clansman author Dixon. A Southerner himself, Wilson permitted the exhibition. Flattered perhaps by the film’s use of quotes from his own book, History of the American People, the president was afterwards quoted as saying, “It is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

Freshly re-titled, The Birth of a Nation opened on March 3 at New York City’s Liberty Theater, at the unprecedented film ticket price of two dollars — and to growing and vocal opposition. In an interview published in the New York American, Griffith disparaged this criticism as “stupid persecution brought against the picture by ill-minded censors and politicians playing for the Negro vote.”

The reaction against the movie brought together an alliance of the black community, led by the NAACP and white social reformers. These included Harvard President Charles Eliot, social worker Jane Addams and sociologist Thorstein Veblen, who called it “a triumph of concise misinformation.” In agreement, the New York Evening Post characterized the film as “a call for racial prejudice.”

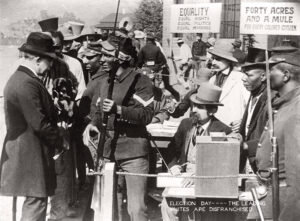

Most flagrant in this regard was the movie’s openly stated white paranoia of being crushed “under the heel of the black South,” leaving unstated the historic oppression of African Americans by the white South. The entire action of the movie’s final hour is triggered by the lust of black men — portrayed by white men in blackface — for virginal white women. The film contends that the real birth of the American nation occurs when “the former enemies of North and South are united again in common defence (sic) of their Aryan birthright.”

Prominent liberal periodicals including The Nation and The New Statesman supported the protests, which led to several local temporary bans on the film. Five weeks after the New York opening, 170 shots comprising nine minutes of inflammatory images were removed. Then the White House issued a statement that the President “has at no time expressed his approbation of it [the film]. Its exhibition at the White House was a courtesy extended to an old acquaintance.”

Birth continued its run at the Liberty for 11 months, selling over one million tickets in New York City, and its distribution spread across the country, drawing huge audiences. In larger markets, Aitken drummed up publicity with opening-day parades of horsemen in Klan robes. Although estimates of its box office returns vary, there is no question that it was the biggest moneymaker of the silent era.

Griffith went on to produce Intolerance, so titled to protest his critics’ intolerance of his right to express his perspective on American history. Though Intolerance was a box office failure, it influenced film editing in foreign cinemas far more than Griffith’s earlier movie. In the meantime, however, Birth drew one more significant response from a portion of the American public.

On the night of November 25, 1915, Thanksgiving Eve, William J. Simmons and 15 others in hooded robes, set fire to a cross on Stone Mountain in Georgia to establish a new Ku Klux Klan. It may be difficult to attribute to the Klan the 1918 spike in black lynchings, but the new group grew into a national organization with more than four million members over the 1920s.

During Reconstruction, the Klan had no organized structure. The name was adopted by many separately formed local groups of masked terrorists intimidating African Americans. Once the Jim Crow laws were in place, there was no more need of them; the terrorism had become institutionalized. From that time on, being black in the South was like living in a police state. The 20th-century national Klan’s network supported this system of oppression well into the Civil Rights era.

The Birth of a Nation cannot be simply dismissed as a reflection of its time, an acceptance of prevailing American social attitudes. Griffith not only accepted such attitudes — he encouraged their belief and anchored them more firmly in our living experience, as is still evident today.

Answering accusations of being against people of color, Griffith is quoted in Gish’s autobiography as saying, “[T]hat is like saying that I am against children…they were our children whom we loved and cared for all our lives.” The depth of this love and care may be fathomed in the words of Cora Hawkins. She had been a maid in Griffith’s New York household for years before his move to California. If she was not born a slave, her parents almost certainly were.

After seeing the movie, she went to Griffith’s rooms at the Astor Hotel to tell him, “It hurt me, Mr. David, to see what you do to my people.”