by Michael Goldman

When director Quentin Tarantino visualized his newest revenge Western, The Hateful Eight, as a 70mm widescreen production, sold it to distributor The Weinstein Company as such, and eventually upped the vintage widescreen aesthetic further by unearthing vintage lenses at Panavision and filming it in a format that Hollywood had not even attempted to use in almost 50 years — Ultra Panavision 70 — his intent was to make a piece of cinema that was a throwback to the rich, special- event theatrical spectacles of the analog era.

Ultra Panavision 70, in fact, was only used for 10 films in history, including Ben Hur (1959) and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), and none since 1966’s Khartoum. When cinematographer Bob Richardson, ASC, discovered the lenses used on those films last year, and Panavision said it could restore them, Tarantino decided to go full bore and make The Hateful Eight the first Ultra Panavision 70 made in half a century. In a limited release December 25, it will be exhibited about as wide as can be imagined — essentially anamorphic 70mm, with a 2.76:1 aspect ratio.

Tarantino went to these lengths for a story about eight violent strangers who cross paths in a claustrophobic, snowbound Wyoming cabin called Minnie’s Haberdashery, with some or all of them having the deadliest of intentions. But along the way, the unusual and ambitious nature of the plan required a host of related technical projects beyond restoring the single existing set of dormant lenses to make sure the whole thing would work out as Tarantino envisioned (see sidebar, page 64.)

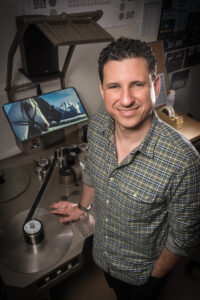

On the editorial side, editor Fred Raskin, ACE, was tasked with cutting two versions of the movie: one for 70mm exhibition, dubbed the “Road Show” version — complete with musical overture and an intermission — and a slightly shorter, digitally scanned “Multiplex” version, which is slated to go wide in early 2016, weeks after The Hateful Eight Road Show version debuts on Christmas in 100 theatres across the country.

But for Raskin, on the creative level, the differences between this project and what he was used to in Tarantino’s world were subtle, but important. At the end of the day, he came to realize that The Hateful Eight was certainly “a different animal than anything on which I’d previously worked.”

Raskin was serving as editor on his second film for Tarantino following 2012’s Django Unchained and, before that, as an assistant to the director’s longtime editor and friend, the late Sally Menke, ACE. Raskin recently spoke with CineMontage about how unusual, and enjoyable, working on the project ended up being. Following are highlights from that conversation.

CineMontage: What was your reaction when you started seeing Bob Richardson’s Ultra Panavision 70 footage? Had you and Tarantino discussed how the nature of this particular format would impact your cutting style?

Fred Raskin: I’m a little ashamed to admit that, aside from my general excitement at seeing 2.76:1 compositions, I don’t think I was aware there would be any difference creatively. But once the footage started coming in, the combination of the beauty of the 70mm and that super-wide aspect ratio led us to hold on to wide shots substantially longer than we would have otherwise. When you are seeing these beautiful compositions — and the clarity of the image is such that you can see the depth of the performances in the actors’ eyes — why would you cut away?

There’s a scene in which Jennifer Jason Leigh’s character plays guitar. In the 70mm Road Show release, the scene plays out in one long take, while in the Multiplex version, that same scene contains a handful of cuts. Quentin felt that holding that long on one take wouldn’t have had the same impact in the digitally exhibited version.

CM: How does this film compare to Djanjo Unchained and other Tarantino films?

FR: This movie is definitely a different animal than Django Unchained, as the piece is inherently more theatrical. Because of the nature of the shoot, the cast had to be off-book from day one. There were certain sequences that needed to be shot while it was snowing, so every shoot day had an exterior scene to be shot if it snowed, and an interior

scene to be shot if it didn’t, and the weather [on location in Telluride, Colorado] was not exactly predictable. With every cast member having committed the screenplay to memory, it allowed Quentin to shoot 11-minute-long takes if he wanted to [since Panavision and Kodak teamed up to build customized, 2,000-foot film magazines so Tarantino could use longer film rolls than normal during production]. More often than not, the question wasn’t “When do we cut to another angle?” It was “Do we even want to cut to another angle?”

To complicate matters, Quentin and Bob came up with beautiful camera moves as our characters are making their way through Minnie’s Haberdashery. Deciding which of those moves was best for each moment was frequently challenging. While the piece may appear to be inherently theatrical, the camera placement and shot design are entirely cinematic.

The movie is also a little different than Quentin’s previous films in that the characters are rarely being entirely honest, and some of them are being entirely dishonest. So, while Quentin would normally hold on whoever is speaking, in this movie we are using a lot of reaction shots to highlight who believes what is being said — and who doesn’t. Quentin likes to say he’s used more reaction shots in this movie than in all his previous films combined.

CM: Structure-wise, this is also one of Tarantino’s more complicated screenplays. And then, in the 70mm version, there is a break in the middle for an intermission. Can you talk about some of the more unusual aspects of that structure?

FR: The movie is broken down into six chapters, and Chapter Five opens before Chapter One has begun, providing key backstory information for four of the titular characters, so that you go into the last chapter knowing where everyone’s loyalties lie…or nearly everyone’s anyway.

There are also both flashbacks and voiceovers. As the second act begins, there is a short narrated sequence recapping what took place before intermission, with Quentin himself delivering the voiceover. An interesting note is that, in April 2014, the piece was staged in front of an audience as a benefit for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art film program, with Quentin reading the stage directions. Hearing him read his writing aloud, occasionally interjecting his own commentary, was one of the more fun aspects of the live read, and his narration in the film echoes this, allowing him to inject his personality into the viewing experience. That section leads into a flashback, in which we see the scene that ended the first act from a different perspective. And the new information we are given sets up the remainder of the movie.

The flashbacks that are incorporated into the sequence that ends the first act were a lot of fun to put together. That is when Major Warren [Samuel L. Jackson] tells General Smithers [Bruce Dern] how his son died. Quentin shot camera moves that started in present-day material and finished in the flashbacks, and also had pieces of dialogue that would cross over. Warren starts telling Smithers what his son said, and then we cut to a flashback of Smithers’ son finishing the line, but with Sam Jackson’s voice coming out of his mouth.

CM: What are the differences in how the Multiplex version is cut together from the Road Show version?

FR: There are two obvious differences, which is that for the Multiplex version, the overture — a three-and-a-half minute piece of music that plays over a single graphic — has been removed, as has the intermission. The scene that ends Chapter Three — the Warren/Smithers confrontation — is a bit of a shocker, and definitely leaves you wanting to talk about what you’ve just seen. So when the decision was made about where to place the intermission, it was a no-brainer. The Multiplex version goes right from Chapter Three to Chapter Four.

Additionally, there are a few scenes for which we cut shorter versions, utilizing different footage. One of the notable things about the Road Show versions of movies back in the 1960s is that they would generally be approximately 10 minutes longer than regular release versions, so Quentin’s plan has always been to emulate that. As mentioned earlier, in one instance, a Multiplex edit came about because Quentin didn’t think the Road Show version of the scene would play in the digital format. In another instance, there was a brief, but very entertaining dialogue exchange between Kurt Russell and Tim Roth that we realized could potentially be dropped. We tried an alternate cut in which we removed it, and it absolutely worked, but we missed the fun of that 20-second exchange.

So it lives in the Road Show version, and it’s gone from the Multiplex version. Releasing multiple versions has allowed us to have our cake and eat it too.

CM: How was editorial set up on this picture?

FR: We were on location in Telluride for the first two months of the shoot. The construction department converted some empty office space into a cutting room that conveniently was located a half-block away from the theatre we used for our dailies screenings. Once production relocated to Los Angeles, we were set up at Sunset-Gower Studios, where our production office was based. And once production came to a close, we moved to a space in Hollywood. Quentin and Sally never worked on a studio lot, and when we started Django Unchained, Quentin told me he wanted to continue that trend. While staying away from a studio lot may be somewhat untraditional, it’s created a friendlier atmosphere, and I think that’s why it appeals to Quentin.

CM: What was your method of collaboration with Tarantino on this movie?

FR: We screened film dailies together while we were shooting in Telluride, and he’d lean over and let me know if there was something specific that he liked. Or I’d make a point to note whenever he laughed, which, as I learned during Django, was a pretty good indication of his happiness with a particular beat. He doesn’t watch a frame of edited footage during production as, at that point, he just wants to stay focused on shooting. So during production, I’m assembling the material based on the notes I’ve taken during dailies screenings. Once the dailies screenings stop — and it seems they nearly always do, eventually — I have to rely on the script supervisor’s notes and my gut instinct.

Once we get into post, however, Quentin is in the room as often as possible. It makes sense; he puts his heart and soul into writing and directing the material, and he wants to put the same amount of care into the editing process. It never becomes a slog. We have a lot of fun working with the footage, exploring different takes, laughing our asses off at highly inappropriate moments in the picture, and, of course, wasting too much time talking about movies. But he’s incredibly dedicated to the process. We’ll work side-by-side for anywhere from eight to 10 hours. Then he’ll go home and watch the dailies for the section we’ll be tackling the next day, taking detailed notes, finding his top two or three performances for any given moment. While he’s doing that, I’ll be tweaking the work we did that day, adjusting the sound effects and mixing it, and then the next day, we pick up

wherever we left off.

Whenever we finish a scene, we’ll bring in about half of the crew to watch it and to give us their thoughts. This was something that Quentin and Sally would do all the time when I worked as an assistant on Kill Bill, and it really made us feel as though we were all making a creative contribution to the movie. Now that I’m in the editor’s chair, I find those screenings invaluable.

CM: We’ve talked about the unique nature of this ultra-wide picture and bringing back this vintage format, but what about the role of sound? How was it used to help tell Tarantino’s story?

FR: The contributions of our sound editorial department, headed by supervisors Wylie Stateman and Harry Cohen, were huge. Quentin knew from the beginning that for much of our time spent in Minnie’s Haberdashery, he would not be using music. He wanted sound effects to carry us, and to create tension in the small space. We talked about the element of the wind from the very beginning. There is a rapidly escalating blizzard just outside throughout the majority of our time at Minnie’s, and we would be using the wind and the clatter of shutters and other storm-related effects to fill the backgrounds and essentially act as music.

CM: We mentioned Sally Menke earlier, who tragically passed away five years ago. When you worked as her assistant on the Kill Bill movies, what did you learn from her about your craft in general, and in terms of how best to collaborate with Tarantino specifically?

FR: Sally was a brilliant editor, and I had my “What Would Sally Do?” sign hanging beside my Avid from the first day of shooting. I can’t tell you how many times I turned to that sign in the hopes that it might give me an idea. Sally had an innate understanding of how important knowledge of the character’s motivations is to putting a scene together. All I can do is attempt to emulate her. One of the things she taught me about Quentin’s work was that he comes up with neat, out-of-the-box ideas, but he’ll only do them once per movie. Being aware of that pushed me to search for things while I was working on my assembly — an unexpected match cut between two different scenes, or an odd sound effects choice, for example. And even if they never made it past my assembly, having that “anything goes” attitude kept me in the right frame of mind for this picture.