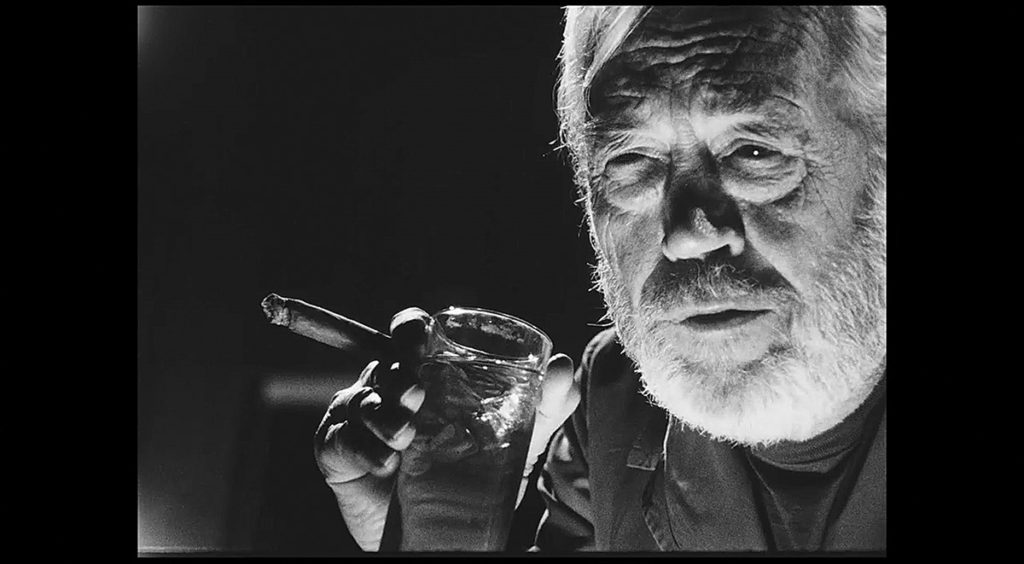

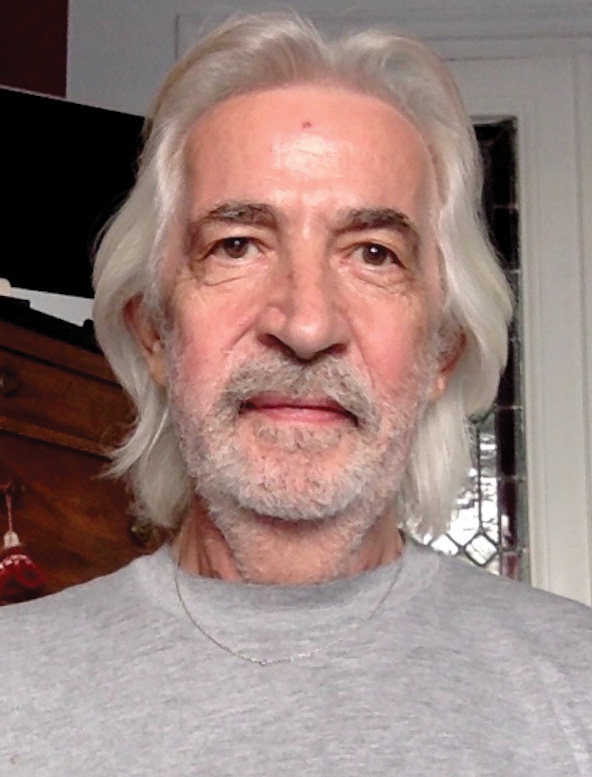

by Peter Tonguette • portraits by Martin Cohen

Few directors were more familiar with the pleasures and perils of film editing than Orson Welles. On the one hand, his best films owe much of their power and potency to the innovative, imaginative work of such editors as Robert Wise, ACE (Citizen Kane, 1941), and Fritz Muller (Chimes at Midnight, 1965). But on the other, Welles considered such otherwise stellar films as The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Touch of Evil (1958) to have been spoiled by re-cutting ordered by studio executives.

Netflix/José María Castellví

So, in his 1978 documentary Filming Othello, Welles spoke with unique authority and bluntness about the power contained in the cutting room. “When we say that we’re ‘editing’ or ‘cutting’ a film, we aren’t really saying enough,” Welles explained, posing behind a Moviola. “Movies aren’t just made on the set. A lot of the actual making happens right here… Here, films are salvaged — saved, sometimes, from disaster — or savaged out of existence. This is the last stop on the long road between the dream in a filmmaker’s head and the public to whom that dream is addressed.”

In the case of The Other Side of the Wind, which was filmed in the early-to-mid-1970s, Welles attempted to “save” that (until now) unfinished film many times over. A succession of editors joined him in his efforts to shape, refine and make sense of the film, which revolves around the close yet fraught relationship between two directors — one on his way out the door, Jake Hannaford (John Huston), and the other on his way up the ladder, Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdanovich).

After decades of delays, Netflix released Wind earlier this fall. Yet, according to the editor hired to finish the film, Bob Murawski, ACE, the legacy of its original editors remains; Murawski estimates that nearly a third of the film features material fine-cut by the director and his colleagues. During the past year, CineMontage spoke with several of the editors who helped Welles achieve the dream that for so long existed only in his head.

The French Connection

In the early 1970s, editor Roberto Silvi — later renowned for cutting several of the final films of Wind co-star Huston, including Under the Volcano (1984) and The Dead (1987) — was among the first to reckon with material from the Wind footage. At the time, he had just a single film to his credit as editor, but the opportunity to collaborate with Welles — then living in Strasbourg, France while he appeared as an actor in Claude Chabrol’s Ten Days Wonder (1971) — was too good to pass up.

“He wanted to do editing of some movies during the shoot in France,” Silvi tells CineMontage. “He rented a villa and we stayed there. We had the cutting rooms.” He and Welles worked on a variety of unfinished projects, including an adaptation of Don Quixote (1972) and the thriller The Deep (1970), but also significant portions of Wind. “We were watching a lot of the dailies for The Other Side of the Wind,” the editor remembers. “One day we watched for two or three hours… There was quite a lot of material, but it wasn’t finished whatsoever.”

Courtesy of Quentin Devlay

The overall shape of Wind was in place then, but large chunks were absent. “Story-wise, it was all there, but there were still some holes,” Silvi comments. “I know he was saying, ‘I have to do this; I have to do that.’”

Throughout the process, the editor paid close attention to the master at work. “To be honest with you, he was doing all the editing,” Silvi concedes. “I was totally intimidated. Most of the time, I was listening.” The editor also learned from the director to not take the work too seriously. “We used to work for one hour,” he remembers. “He would say, ‘Okay, Roberto, do this cut from here to there.’ In those days, we used to work with the guillotine. He said, ‘Oh my God, that’s a great cut. Let’s go and celebrate it and have something to drink. That’s the best cut of the day.’

“He put me at ease immediately,” Silvi continues.” I used to call him ‘Mr. Welles.’ He said, ‘No, call me Orson.’ He would speak in Italian — his beautiful voice in Italian. I have a great memory of him.”

Welles seems to have been more focused on completing Wind by 1973, when editor Yves Deschamps entered the director’s orbit in Paris. The director’s main editor at the time, Marie-Sophie Dubus — who had cut his essay film F for Fake (1973) — had injured her arm, so Deschamps was asked to work on introductory segments for the Welles-hosted ITV series Orson Welles’ Great Mysteries (1973-1974). “It was the kind of thing Hitchcock used to do for his TV program,” he explains to CineMontage. “I must say that it worked. He was very happy with it.”

With Dubus still sidelined, Welles invited Deschamps to start cutting Wind, confiding in the editor that he was in need of a producer. “I said, ‘It’s impossible that somebody like you is without a producer, so I can introduce you to 10 producers who would be very, very happy to work with you,’” recalls the editor, who guided Welles to work with Dominique Antoine (who indeed became one of the film’s producers). “They had a deal,” he says, “so that’s how I started the adventure of The Other Side of the Wind.”

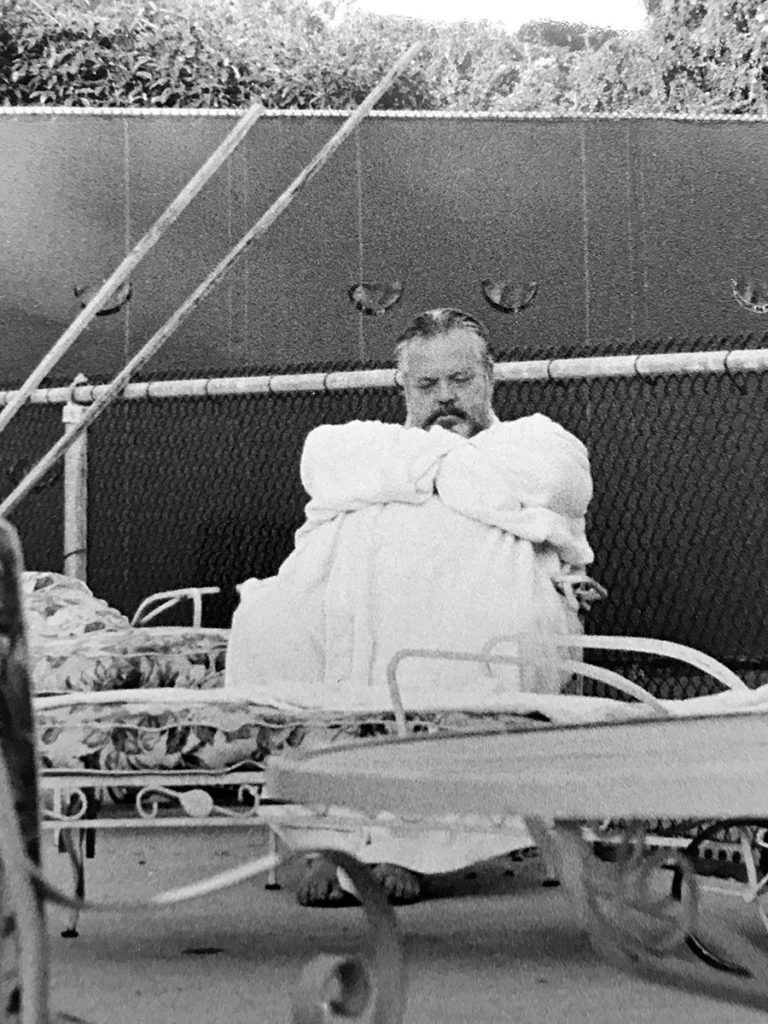

First, however, came the question of where to edit Wind. After plans to cut in Los Angeles and Madrid were aborted, Deschamps was requested to return to Paris to work at a facility called Auditel. “The problem at Auditel was that there was a 26-step staircase, which was torture for Orson,” he remembers. “He was something like 340 pounds at that time. He was so heavy that his legs couldn’t work very well.”

In the end, Welles set up shop at LTC, where Deschamps, fellow editor Arnaud Petit and a number of assistants manned five editing machines over the course of about six months. “We used to put on each machine the material of a reel he wanted to work on,” the editor explains. “He went from one to another one to make the marks with a pen on the cellophane, saying, ‘I want this part and that part of the shot.’”

The director assembled select rolls consisting of takes he preferred, but he delayed in making a commitment. “He could have three, four, ten times the same line,” Deschamps recounts. “He kept the things a long time together until he finally chose one. It’s a wonderful editing method, but a very long one.”

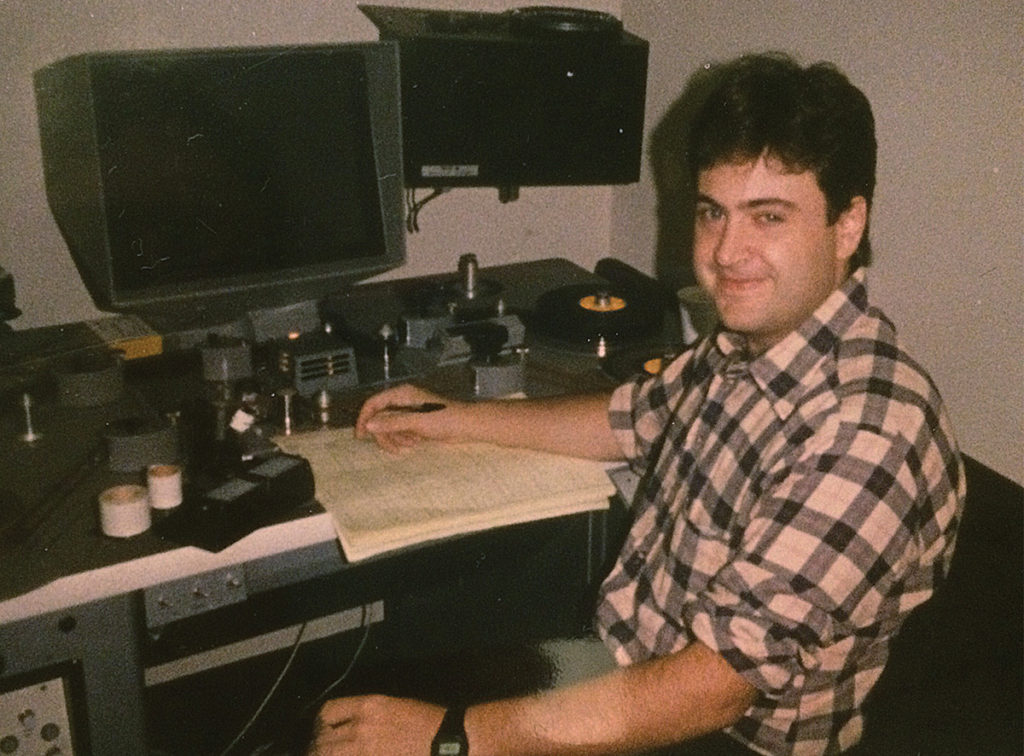

Courtesy of Steve Ecclesine

Although Welles may have been focused on individual bits and pieces of Wind, Deschamps says that the filmmaker never failed to have the larger project in mind. “He always had in his head all the cuts of the film and the arc — the dramatic arc, the rhythmic arc, the musical arc — of the film,” he offers. “When he looked at one moment, he was thinking of 2,000 other moments.”

For his part, the editor often found himself cutting in the dark. “When we started to work, I asked Orson if he could give me a script, and he said, ‘Oh, no, no, no — you don’t need any script. I have it in my head,’” Deschamps reveals. “I understood later that this was the first manifestation of his paranoia. He didn’t want somebody to know what he was trying to tell.” Seeking to better grasp the film, he later examined all of the material, further angering Welles.

In fact, Welles had grown wary of Deschamps due to his association with Antoine. “He was very, very suspicious of people when they were close to the production,” he claims. “I was very close to Dominique Antoine, and that’s why I introduced her to him. But at that one moment, he decided that I could steal his movie and give it to the producers.”

Having reached his limit, the editor finally stepped down from Wind, but his sometimes maddening relationship with Welles didn’t dampen his appreciation for the filmmaker’s editorial acumen. “He was the perfect editor,” Deschamps reflects. “If you want to know what kind of editor Orson was, look at F for Fake. It’s just a crazy, crazy work of editing. Probably too much, too bright, too fast for the audience — but he was an incredible inventor, an incredible master of the rhythm.”

Following Deschamps’ departure, Dubus and Welles reunited, working on Wind for about six months in Rome, as she recounted in a 2005 interview for this author’s book, Orson Welles Remembered, published in 2007.

“It was always very long because he didn’t want to change the scenes, of course, but nevertheless he changed them because sometimes he cut with a lot of close-ups, sometimes he re-cut with very wide shots,” said Dubus, who died in 2012. “So each time was a different film, a different feeling of the sequence.”

The French editors’ experiences on the film may have been fitful or frustrating, but their work paid dividends; by the mid-‘70s, Wind was nearing the finish line. “When he finished with Marie-Sophie after Rome, Oja told me that Orson considered the film almost finished,” Deschamps recalls, referring to Welles’ companion (and Wind co-author and co-star) Oja Kodar. “Some reels were already mixed. I thought at that moment that the film was 90 percent finished — maybe between 80 and 90 percent finished — and it was very close to the end.”

On the Move in LA

Steve Ecclesine, who served as an editor for Welles from 1974 to 1976, confirms this view. Currently a producer in film and television, he worked with the director on Wind as the two hopscotched across Southern California. “Too many people knew where he lived; too many people had his phone number,” Ecclesine confides to CineMontage. “In the very beginning, it was a mansion in Beverly Hills. When it was time to leave there, we would go and hide out at the Beverly Hills Hotel, in one of the cabanas for a week or two weeks until another place had been located. We ended up at Bogdanovich’s place, which was in Bel Air.”

During his stint on Wind, Ecclesine remembers that Welles was still shooting new footage, but it was incidental — rather than essential — to the overall film. “It was basically the last gasps,” he explains. “It was the last pieces that he wanted to finish up.” The editor didn’t re-work scenes that had already been fine-cut, but he worked with Welles on fine-tuning those that needed further attention.

One memorable scene on which the pair labored was from Hannaford’s film-in-progress, a deliriously trippy scene set in the bathroom stall of a nightclub and featuring a rain-soaked appearance by Kodar. The scene consisted of material shot in multiple locations, with years between the shoots.

“We were intercutting this scene that had been shot four, five times — once in London, once in New Mexico, once in LA,” Ecclesine recalls. “It’s just going by boom, boom, boom. There are 500 edits.” (The post-production team that assembled Wind in 2018 was unable to find an edited version of this scene, so it was reconstructed from scratch.)

Ecclesine also remembers Welles having prepared two work prints for Wind. “I cut one together,” he claims. “We had to go down to the lab and look at it on a double-system projector, so you had to take all of the single guillotine splices and you had to double-reinforce them because you couldn’t feed a single spliced 35mm print through a double-system projector. You had to have tape on both sides of every cut, so I had to go through the whole thing and basically double-splice the entire film.”

Murawski and the post-production team never found a complete, edited cut of Wind; perhaps it has been lost, or maybe Welles undid his own work as the years marched on.

According to Josh Karp’s definitive book Orson Welles’s Last Movie: The Making of ‘The Other Side of the Wind’ (2015), the negative ended up in Paris, due to disputes between Welles and an Iranian production company — but the director was able to toil away on the work print.

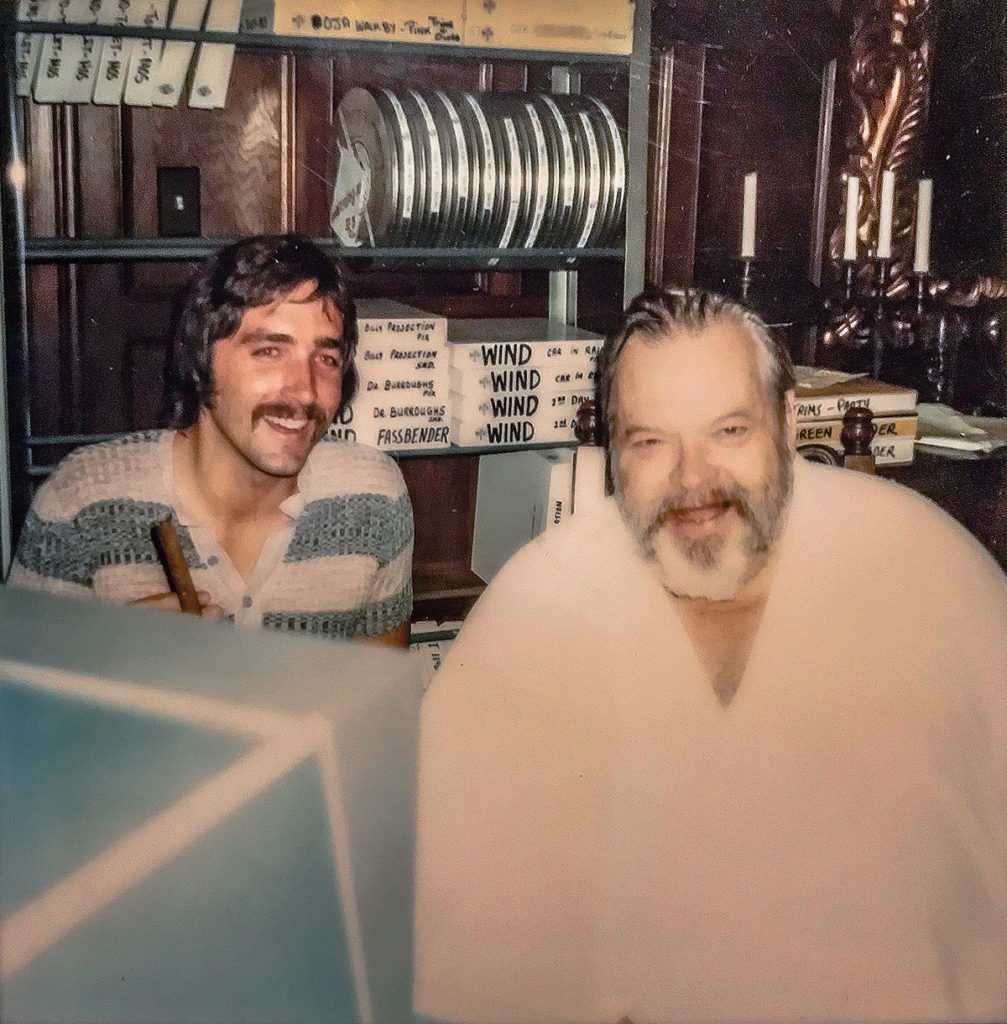

In fact, in the early 1980s, Welles was embarking on a major effort to revisit Wind. Material from multiple unfinished films was being shipped to his then residence at 1717 N. Stanley Avenue in Los Angeles. There, scenes were to be catalogued and organized by his current — and final — editor, Jonathon Braun, ACE. Later an Emmy-nominated editor who specializes in reality television, he parlayed a friendship with Welles’ longtime producer, Alessandro Tasca, into a gig working with the filmmaker starting in 1982.

Assigned by Tasca to pick up from the lab and put together the dailies from Welles’ unfinished Isak Dinesen adaptation The Dreamers (1982), Braun proceeded to prepare a kind of initial cut of the scenes. “In those days, the picture and soundtrack needed to be synched together first before editing, and it was not uncommon for the editor to do a rough assembly based on script notes, which I happened to find in the film boxes as well,” he explains to CineMontage. “Tasca called me later and said, ‘What the hell did you do? I only asked you to sync the dailies. Nobody has ever edited Mr. Welles’ material without him being there!’ Luckily, Orson liked what I did.”

Having hit it off with Welles, the young editor was given the responsibility of setting up an editing studio in the Stanley guesthouse and sorting through the director’s myriad projects. “As I found stuff, I would watch stuff,” Braun remembers. “I started watching The Other Side of the Wind. I saw John Huston, who I was a big fan of. And I saw Peter Bogdanovich, who I was also a big fan of. The more I watched it, the more I said, ‘Oh, there’s something in here. This is fascinating.’”

Braun encountered material that took a variety of forms: Some scenes were fully cut, but others remained as dailies or featured alternate takes. “Orson was big on going back and looking at other takes,” he comments. “Most of it had been gone through, but there were definitely sections that weren’t touched yet.”

When working with Braun, Welles prioritized projects that he was actively trying to complete or sell — for example, a talk show pilot with Angie Dickinson and the Muppets, or his essay film on the art of illusion, Orson Welles’ The Magic Show (1985). Yet the director and editor still found time to re-examine scenes from Wind.

“I remember the bus scene, where the crew people are being taken with the mannequins of John Dale [Bob Random],” Braun recounts. “I remember working on that and Orson wanting me to put takes back-to-back of certain lines so that he could see what another reading would be like. But he wanted me to cut it loosely so that he could tighten it later.”

Despite the age and experience gap between the two, the editor also felt free to make suggestions — gently, of course. For example, Braun felt that some of the film-within-the-film scenes were cut too fast. “Some of the scenes needed to be fast, like the party scene where it was just like a cacophony of visuals,” he says. “But to differentiate the two films, I thought maybe the film-within-the-film needed to be stylistically slowed down a little bit.”

And, if Welles had managed to shepherd Wind into release before his death in 1985, Braun was ready to help put the film into shape. “If we had finished it, it would have been a huge undertaking,” the editor suggests.

The Original Editors’ Reactions

While working on Wind in 2018, Murawski sought feedback from several of the project’s original editors. For their part, they praise the undertaking to bring the long-delayed project to audiences. “Bob’s contribution to finishing this — Orson’s last film and the final of his legacy — was outstanding,” Braun says. “I always know something must be good when I can’t think of how I would’ve been able to do better. As I said to Bob after seeing it the first time, ‘Amazing work. You’ve really done Orson proud!’”

Deschamps declined to finish Wind after Welles’ death. “I said, ‘I won’t’; first, because I promised to him not to touch one single frame without him,” the Frenchman recalls. “Second — the main reason — is that only Orson would have been able to say what he wanted to do with that.” Yet he too appreciates the efforts of Murawski and his colleagues: “I really admired the patience, the talent and the perseverance of Bob to go until the end of the process,” he says.

Silvi also applauds the editor’s handiwork — and contribution to film history. “I think Bob Murawski did excellent work, considering all the problems the movie had from the beginning,” he opines. “I’m very happy that there finally will be, I hope, recognition for two of the most important figures of the cinema industry: Orson Welles and John Huston.”

Adds Ecclesine, “I’m sure Welles would be happy that it’s finally getting out there. He’s smiling from wherever he happens to be sitting at this point.”